What truths lie in the ancient bones of a teen? Scientists are finding out

"The research is like putting together a 1,500 plus piece puzzle."

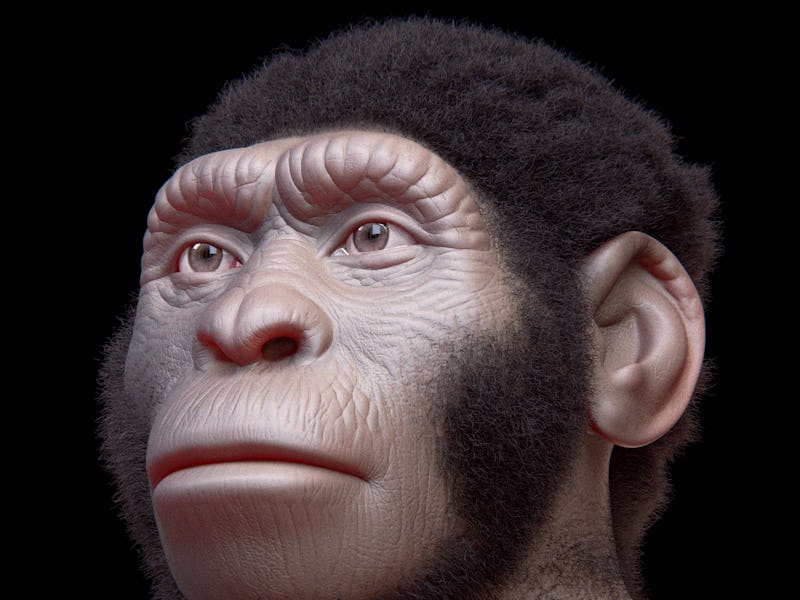

Homo naledi, an ancient species of human, practiced a custom that's now boon to scientists: Just like modern-day humans, they intentionally buried their dead.

Paleoanthropologists discovered these burials in the Rising Star cave system in South Africa in 2013. To date, seventeen Homo naledi, skeletons, all of various ages, have been found there. They offer an unprecedented look into these ancient humans' lives.

And now, in a new analysis of 70 skeletal fragments seemingly from a 15-year-old Homo naledi, scientists can glimpse a key period of their development — the transition to adulthood.

Because these archaic humans share characteristics with Australopithecus (like the infamous "Lucy") and other early Homo species, Homo naledi remains offer a unique opportunity to understand early human evolution.

The fragments analyzed in the new study are thought to have belonged to a single juvenile, identified as DH7. Their bones were pulled from the Dinaledi Chamber, and date to 335,000 to 236,000 years ago.

DH7's bones and teeth display a mix of maturity patterns — in some ways, appearing more like modern humans, and, in others, appearing far more ancient. Ultimately, the assemblage of this skeleton into one individual is an unprecedented look at an ancient youth.

"The research is like putting together a 1,500 plus piece puzzle, but missing the picture on the top of the box," study first author and anthropology professor at Modesto Junior College Debra Bolter tells Inverse.

"The thrill is when the picture comes into focus, in this case, reconstructing a demographic profile of the life stages of an extinct species."

This analysis was published Wednesday in PLOS ONE.

The partial skeleton of DH7.

Bolter first led a team in the analysis of immature Homo naledi in 2014, during a workshop hosted by paleoanthropologist Lee Berger. Berger led the original expedition that resulted in discovering Homo naledi.

In Bolter's research experience with wild monkey and chimpanzee skeletons, she developed new ways to categorize how teeth and bones sort individuals from different age groups, as well as show signature patterns of maturity for a species. She and her team applied the same methods to this individual.

Immature remains "are critical for understanding how an extinct species matured," Bolter explains.

But because they are very few pre-adult skeletons in the fossil record, she says, reconstructing the remains of this teenage Homo naledi is "a major break-through in paleoanthropology."

It was once hypothesized that brain size sets the pace of maturity, meaning that having a larger brain suggests that the extinct hominin species likely needed more time to mature.

But armed with these new findings and previous research, we know that is not necessarily the case, Bolter says. For example, we know that while the Homo erectus has a brain size twice that of a chimpanzee, it grew up at the same pace as chimps.

"So there are other features that are driving the elongation of the life stages in hominins, and humans in particular," Bolter says.

"Homo naledi, with its smaller brain size and smaller body size, but its sophisticated behavior of caching dead individuals inside the Rising Star cave system, may give us some clues to what those selective pressures could be."

The study represents the first step in the process of understanding Homo naledi maturity patterns. One theory Bolter wants to test is whether, when it came to this human, a prolongation of immaturity allowed them to learn more complex behavior.

It would also more definitively pinpoint the age of this adolescent specimen. If the Homo naledi matured more like Australopithecus, then DH7 is estimated to have died between the ages of 8 and 11. But if it had a slower growth rate, like living humans, then it may have been closer to 15-years-old at the time of death.

Further study, focused on using techniques to determine the age of a fossil at death, is needed to say for sure — and more juvenile remains could be assembled together using forensic techniques.

For now, we have DH7 — a human being frozen in eternal youth.

Abstract: Immature remains are critical for understanding maturational processes in hominin species as well as for interpreting changes in ontogenetic development in hominin evolution. The study of these subjects is hindered by the fact that associated juvenile remains are extremely rare in the hominin fossil record. Here we describe an assemblage of immature remains of Homo naledi recovered from the 2013–2014 excavation season. From this assemblage, we attribute 16 postcranial elements and a partial mandible with some dentition to a single juvenile Homo naledi individual. The find includes postcranial elements never before discovered as immature elements in the sub-equatorial early hominin fossil record, and contributes new data to the field of hominin ontogeny