The optimal diet for longevity comes down to this critical factor

When it comes to macronutrients "people need to get away from ‘unidimensional’ thinking."

What we eat has the potential to either increase or decrease our lifespan. But aside from this essential truth, how to eat to our best advantage is up for debate.

In a study released Monday, researchers offer some clues — and pose new questions. They argue human mortality is largely influenced by a balance of macronutrients — with the stipulation that the makeup of this balance should change across lifespan.

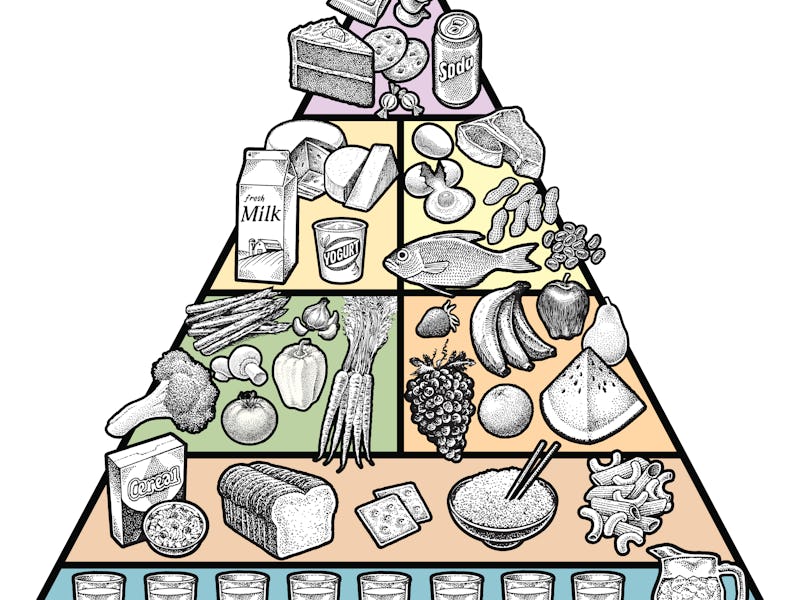

Macronutrients provide the body with energy, and the body needs them to maintain its structure and systems. These are the building blocks of meals you know well: carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

This study suggests macronutrient supplies — defined as a country's overall supply of macronutrient rich food — are a strong predictor of age-specific mortality, a finding which held even after the researchers corrected for economic factors.

This is different from macronutrient intake, the absolute amount of specific macronutrients you eat, is what is most important in influencing longevity. The study claims it's the availability of macronutrients that’s a strong predictor of mortality patterns, and from there, showed how the ideal balance of supplies for maximizing lifespan changes with age.

First author Alistair Senior is a research fellow at the University of Sydney. He tells Inverse that in future studies he’s interested in “trying to nail down the discrepancies between supply and intake.”

"People need to get away from ‘unidimensional’ thinking [like eating less fat or avoiding carbs."

But he argues this study does get at the question of intake — what should you actually be eating — in some critical ways. Essentially, it demonstrates that’s critical to not take an all-or-nothing approach to diet.

Senior and his colleagues found that optimal diet composition for reducing mortality risk varies with age. Below the age of 25, mortality rates were closest when the total energy supply consisted of 16 percent proteins and 40 to 45 percent of both fats and carbohydrates.

But in later life — if an individual is more than 55-years-old — the balance changed to a total energy supply of 11 percent proteins, 67 percent carbohydrates, and 22 percent fats. It was no longer best for survival for the percentage of fats and carbohydrates to be equal.

These findings were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

You can’t go micro on macro — Senior is hesitant to extrapolate his findings directly to dietary advice, but he does say they demonstrate “focusing on one aspect of your diet could be leading you down a blind alley.”

“People need to get away from ‘unidimensional’ thinking [like eating less fat or avoiding carbs],” he says.

“Nutrients inevitably come parceled up together in the foods we eat, thus if you focus on, for example, increasing your protein intake, you could be inadvertently altering some other aspect.”

It’s a logical take that’s perhaps forgotten in a world of dietary fads. The Atkins diet, for example, restricts carbohydrates and encourages eating more protein and fat. The Keto diet endorses nearly the same, even raising the percentage of fat intake.

Senior’s research indicates that it’s a balance of different macronutrients — not the elimination of any — that improves the chance of survival. Furthermore, this balance changes: When you’re young, equal amounts of fat and carbohydrates are key, and in older age, it’s necessary to reduce fat in exchange for carbohydrates.

This conclusion is based on a dataset analysis including 1,879 life tables from 103 countries, spanning the years 1961 to 2016. Life tables follow a group of people born within the same population in the same year and track the probability that a person will reach a certain age. The scientists obtained theirs from the Human Life-Table Database. They also analyzed these factors in relation to macronutrient supply data from the Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database, and historical data on the gross domestic product per capita for different countries.

Across age groups, the team found that mortality rates were lowest when the energy supply was 3,500 kilocalories per capita per day.

In practice, Senior explains, hitting this number would involve a very high energy diet — which could be constructed in any number of ways — that without offsetting with exercise, is likely to lead to weight gain and obesity.

He notes that “this very high estimate of total energy likely reflects the fact that we are looking at supply rather than intake.”

“A number of factors intervene between what a country supplies per capita and what a person eats, but food wastage will certainly account for a portion of the 3,500,” Senior says. “The numbers of wastage of absolute energy vary a lot by country — as well as within country — but one estimate puts the average in the United States at 1,249 kilocalories per capita per day.”

This touches on a tension in the study of ideal eating: Different countries have different issues when it comes to food. Low supply is a signature of undernutrition, and this contributes to deaths globally. But overnutrition is a signature of wealthy countries — and high supplies of fats and carbohydrates can also lead to high levels of mortality.

That’s helpful for people who set food policy. What’s perhaps most helpful to the average person trying to navigate their diet are the macronutrient composition differences they identified. National supplies of macronutrients reveal patterns in age-specific mortality — and individuals can consider these patterns when making their own eating choices.

Thinking of the ideal later-life energy balance, Senior hasn’t seen “any well-known dietary patterns that tick the box in all three dimensions.”

He does note that a traditional Okinawan diet is low in protein — at around 9 percent — but is higher in carbs — 85 percent — and much lower in fat — 6 percent. There’s also an Okinawan elder’s diet that “gets a bit closer in the carb and fat dimensions” — hitting a respective 58 and 26 percent — but it's higher in protein at 16 percent.

Okinawa, the southernmost prefecture of Japan, is known for its residents’ long life expectancy and, in turn, the high numbers of centenarians. Their longevity hints that they are hitting the right marks — marks that Senior’s research suggests we aim for. Ultimately, it’s about hitting the right balance and avoiding the foods known to cause harm.

Abstract: Animal experiments have demonstrated that energy intake and the balance of macronutrients determine lifespan and patterns of age-specific mortality (ASM). Similar effects have also been detected in epidemiological studies in humans. Using global supply data and 1,879 life tables from 103 countries, we test for these effects at a macrolevel: between the nutrient supplies of nations and their patterns of ASM. We find that macronutrient supplies are strong predictors of ASM even after correction for time and economic factors. Globally, signatures of undernutrition are evident in the effects of low supply on life expectancy at birth and high mortality across ages, even as recently as 2016. However, in wealthy countries, the effects of overnutrition are prominent, where high supplies particularly from fats and carbohydrates are predicted to lead to high levels of mortality. Energy supplied at around 3,500 kcal/cap/d minimized mortality across ages. However, we show that the macronutrient composition of energy supply that minimizes mortality varies with age. In early life, 40 to 45% energy from each of fat and carbohydrate and 16% from protein minimizes mortality. In later life, replacing fat with carbohydrates to around 65% of total energy and reducing protein to 11% is associated with the lowest level of mortality. These results, particularly those regarding fats, accord both with experimental data from animals and within-country epidemiological studies on the association between macronutrient intake and risk of age-related chronic diseases.

This article was originally published on