The Weirdest Werewolf Movie of the ‘90s Was the Apex, and End, of a Surreal Subgenre

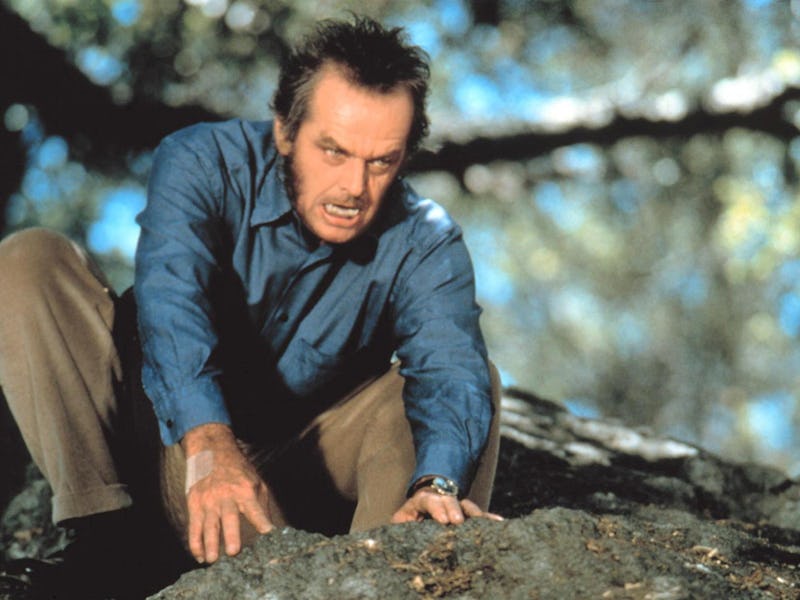

Jack Nicholson played a werewolf in a movie directed by Mike Nichols. The result is fascinating.

Spare a thought for the poor werewolf. It’s never had the pop culture footprint of its paranormal contemporaries and hasn’t inspired the devotion of the likes of vampires, witches, and zombies. Our ravenous lupine brethren just never took off in Hollywood. There are exceptions, of course, but cinema’s favorite fanged ones tend to be undead for a reason. But 30 years ago, Mike Nichols and Jack Nicholson collaborated for an unexpectedly strange addition to the werewolf canon that brought the monsters thoroughly into the ‘90s.

After the unexpected commercial success of Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the film world tried to leap on the trend with more adult-driven horror films inspired by classic literature. The results were largely odd. Kenneth Branagh’s version of Frankenstein is simultaneously brilliant and terrible. Julia Roberts starred in Mary Reilly, a rewrite of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde that was lambasted as boring and pointless. Then there was Wolf. Unlike its monster colleagues, Wolf wasn’t based on pre-existing material, although it took inspiration from 1941's The Wolf Man, one of the main titles in Universal's monster series. Also unlike those other films, which were lavish historical dramas, Wolf was a contemporary story about modern ills and a very decade-appropriate workplace drama. The end result is maybe the weirdest film out of this feverish and surreal subgenre.

Wolf follows Will Randall (Jack Nicholson), editor-in-chief of a major publishing house who is being demoted after a bored billionaire (Christopher Plummer) announces plans to take over the company. He seems doomed to fester away in middle age, but then he is bitten by a black wolf while traveling, and soon he undergoes a change. He grows his hair back, his senses become heightened, and his sex drive is through the roof. It’s been years since Will felt this rejuvenated, but with these new powers come bloodthirst and animalistic urges he can’t control.

For most of its running time, Wolf is basically a workplace story about backstabbing editors trying to one-up each other in the world of elites and smarmy intellectuals. Will’s biggest problem isn’t him growing extra hair or overhearing his colleague’s conversations but his lickspittle colleague Stewart Swinton (a perfectly cast James Spader) who is trying to steal his job while sucking up to him in public. Becoming a werewolf is excellent for business, it turns out, as it revives Will’s waning spirit and turns him into a ruthless deal-maker. His professional peak comes when he reveals his plan to Stewart then urinates on his leg to mark his territory.

In a world where egotistical men in suits backstab their way to the top, adding dog-like characteristics doesn’t change all that much. This metropolitan life, where everyone attends cocktail parties and laments the ills of the lower classes, is basically a politer version of a zoo. When Will begins to embrace his inner wolf, it just reveals how shoddy those pretenses are. It’s less The Wolf Man than The Apprentice, albeit with more pee. What is corporate rivalry if not an extended pissing contest?

Wolf was more cutthroat workplace drama than supernatural horror movie.

Critics dinged Wolf for not being very scary, and it really isn’t a horror film in the end (the most genre-specific thing about it is Ennio Morricone’s gorgeously baroque score). It’s often proudly silly too. There’s only so much seriousness you can put onto watching Jack Nicholson, already one of our most werewolf-y actors, break a fake deer’s neck then howl at the moon while wearing a three-piece suit. Rick Baker’s make-up work is far subtler than one would expect, with unnerving contact lenses doing much of the heavy lifting as the extra hair seems less primal and more like a man who has thrown away his razors.

Wolf is more a dramedy with speculative elements, but when it finds its footing it’s highly effective. The parallels between ravenous wild animals and gross rich dudes who view everything as their playthings is hardly subtle, but it works. When Spader begins his own transformation, he evolves into a proud rapist-in-training, sniffing at Michelle Pfeiffer’s crotch in public and letting everyone know his plans for her. He does so in a public place and nobody bats an eyelid: how often have women had to deal with that? Pfeiffer is also highly believable as a troubled woman who is both enticed and repulsed by Will’s increasingly animalistic behavior (it’s a very horny movie, something this subgenre embraced.) There’s attraction in this grown-up version of the bad boy, but also something to truly fear, especially as it becomes clear that he may have human blood on his paws. The legendary Elaine May script-doctored Wolf and you can see her fingerprints all over the scenes where Pfeiffer goes toe to toe with Nicholson and becomes far more than just another stock love interest.

After Wolf, which was an unexpectedly costly film and didn’t break even, Hollywood changed track with its horror films, moving more towards the meta fare of Scream and teen slashers that were cheaper to make and appealed to a wider audience. It’s a shame because Wolf and its ilk were truly one-of-a-kind films, for better or worse. Nichols and Nicholson seemed caught between classy and trashy with Wolf, but the end result is a perfectly of-its-time work that has a lot to say about how toxic masculinity and the male ego are all too close to outright carnage.