V/H/S/94 review: Shudder’s screwy, gooey anthology is horror at its best

Horror's best anthology series is back.

VHS is dead. Long live V/H/S.

Though analog videotape is considered a relic at this point, the horror-anthology franchise named for it is still going strong — just shy of a decade since Brad Miska and Bloody Disgusting’s first entry debuted at Sundance (then snaking its way to VOD and a limited theatrical bow).

And with its fourth installment, V/H/S/94 (now streaming on Shudder), the franchise has returned in surprisingly fine and freaky form, dispelling the sense of diminishing returns that had crept in across its second and third entries with gripping, gore-soaked bursts of midnight-movie goodness.

A Halloween miracle? That could be the case, but credit is due anyway to this new film’s producers (and, of course, its crack team of filmmakers) for overseeing what feels most like a confident course correction for a franchise many had assumed was past its prime.

When V/H/S hit screens in 2012, it super-charged the disreputable found-footage format with one devilishly simple pitch. Talented genre directors could strut their stuff via horror shorts, knitted together by a frame narrative and further linked by the titular format (all the shorts claimed to be amateur footage, recorded onto VHS tapes and recovered from an abandoned house).

For horror filmmakers on the rise, taking part was a no-brainer. The first V/H/S attracted the likes of Adam Wingard, David Bruckner, and Radio Silence, who’ve since laddered up with projects like Godzilla vs. Kong, The Night House, and Ready or Not. (Next for all three: reboots, of course, with Wingard handling Face/Off, Bruckner overseeing Hellraiser, and Radio Silence on a fifth Scream movie.)

A scene in Chloe Okuno’s “Storm Drain” in V/H/S/94.

The subsequent two V/H/S films followed suit, bringing Welsh action-melee maestro Gareth Evans (The Raid: Redemption) and Indonesia’s king carnage Timo Tjahjanto (The Night Comes for Us, the upcoming Train to Busan remake) into the fold. The films cemented the V/H/S franchise as an R-rated playground for genre filmmakers chomping at the bit to showcase their mean streaks.

But just as the first V/H/S and V/H/S/2 were elevated by their most substantial shorts (Bruckner’s “Amateur Night” and Tjahjanto’s “Safe Haven,” respectively), the third outing V/H/S Viral marked a creative and technical nadir. Its segments ranged from solid (“Bonestorm,” by The Endless duo Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead) to shockingly incoherent (Gregg Bishop’s dark-magician mockumentary “Dante the Great” and Marcel Sarmiento’s abysmal wraparound “Vicious Circles”).

A scene in Chloe Okuno’s “Storm Drain” in V/H/S/94.

And so fans could be forgiven for setting their expectations low for V/H/S/94. Though the reveal of its title, shifting the action of its shorts back to the 1990s, was an early indication that the franchise planned to hit the reset button. So, too was the reveal of a more diverse director lineup than the previous entries.

In the rotation are two franchise familiars — Tjahjanto and You’re Next writer Simon Barrett (who penned shorts in both V/H/S and V/H/S/2) — and a trio of exciting new voices: Jennifer Reeder (Knives and Skin), Chloe Okuno (Slut), and Ryan Prows (Lowlife).

Made on micro-budgets by directors pushing their limits, the best V/H/S segments have always possessed a certain punk-rock mentality. Perhaps shooting under the constraints of the last year has added another kind of stricture that allows V/H/S/94 to bear particularly and productively sour fruit. This is the franchise’s most consistent entry, with no duds to speak of and several of the most impressive shorts this series has housed to date.

A scene in Timo Tjahjanto’s “The Subject” in V/H/S/94.

It is a struggle not to start with Tjahjanto, especially given the teeth-gnashing gonzo brilliance of his previous V/H/S/2 contribution “Safe Haven,” in which filmmakers infiltrate a cult then flee an apocalyptic ritual. Back for blood with V/H/S/94 segment “The Subject,” about a mad scientist and his transmogrified human experiments, Tjahjanto’s visceral approach to horror has perhaps never felt so enjoyably reminiscent of a run-and-gun shooter. A gore-soaked exercise in every sense of the word, “The Subject” toys with perspective in fiendishly clever ways. Its madness, though, flows more from a sense of constant, rapid escalation, as early body horror leads into a slice-and-dice slalom so ambitious and dizzyingly well-executed that it can’t help but blow the other shorts out of the water.

But if Tjahjanto is the project’s greatest showman, in a one-person race for grand-Guignol glory, the other filmmakers bring different strengths. Okuno’s quietly gleeful “Storm Drain” follows a broadcast anchor (a flawless Anna Hopkins) and her cameraman into the sewers, where they’re determined to close in on the urban legend known as Ratman (or Raatma, as it’s known to other drain-dwellers they encounter). Descending through a labyrinth of underground tunnels, “Storm Drain” weaponizes its shadows to tremendous effect — even if the short shows its seams with an eventual monster reveal. That it does so feels like a conscious throwback to creature features from a bygone era when viscid practical effects reigned supreme.

Barrett, who recently moved from writer to director with his feature Seance, pulls off a ghost story that succeeds through admirable, even classical restraint. In “The Empty Wake,” on a dark and stormy night, a young funeral home attendant (Kyal Legend) grows increasingly unnerved by noises emanating from the direction of one recently closed coffin. Its appeal lies in that spooky, straightforward premise, and Barrett’s a sharp-enough technician not to get in its way.

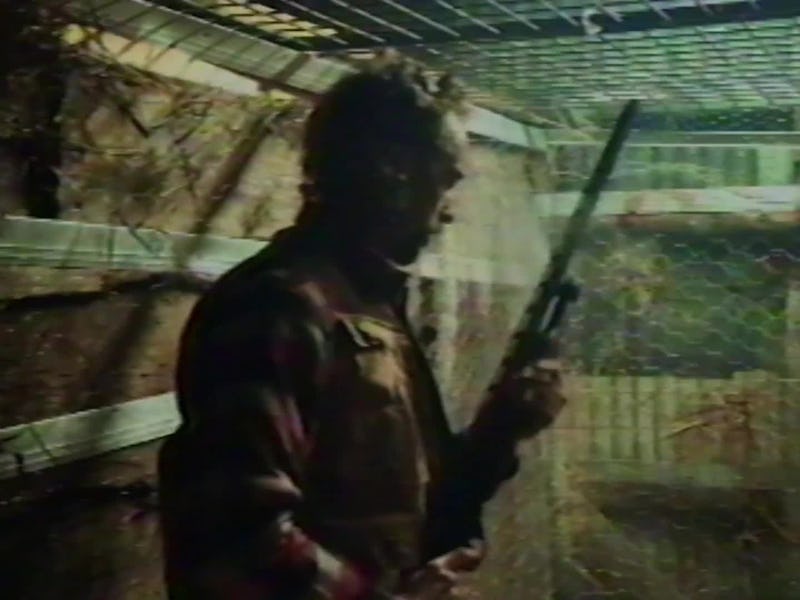

A scene in Ryan Prows’ “Terror” in V/H/S/94.

Ryan Prows is perhaps the most significant find of V/H/S/94 (at least for those unfamiliar with Lowlife), given the technically impressive appearance, barbed humor, and cathartic payoff of “Terror.” Prows’ short follows a white-supremacist militia who plan to unleash a supernatural weapon in their arsenal during their assault on a federal building. Unfortunately, the dimmer bulbs in this bunch get wasted the night before, and that weapon turns on them in a darkly funny fashion. More directly set in 1994 than the other shorts, “Terror” guns for modern resonance and displays a sharp-toothed sense of humor in doing so.

Of all the filmmakers involved in V/H/S/94, this critic was most enticed by the inclusion of Reeder, a brilliant genre deconstructionist whose shorts and legitimately Lynchian feature debut, Knives and Skin, have interrogated the feminine mystique in subversive, mesmeric ways.

That she’s tasked with the always-thankless wraparound segment “Holy Hell” is frustrating because it reduces the potential impact of a filmmaker so skilled at building atmosphere. The short is about SWAT team members who breach a compound filled with upside-down crucifixes, dismembered mannequins, and glowing television sets. However, Reeder wields her intermittent screen time wisely, satirizing the rough-and-tumble masculinity of military grunts and zooming in on their helplessness — and the uneasy, conditional experience of spectatorship itself — in time for an appropriately meta-confrontational finale.

A scene in Jennifer Reeder’s “Holy Hell” in V/H/S/94.

A succinct hook from which its filmmakers can hang their segmented horrors, VHS tape itself has never been utilized as cleverly as it is in V/H/S/94, which goes all-in on era-accurate grain. For some, the new film will be a textural pleasure most of all. Skips, scratches, static, pops and blips on the audio all add a sense of tattered authenticity to the shorts, many of which employed analog equipment. The image quality degrades noticeably as scary bits approach, reminiscent of the way videotapes would get worn out by being rewound and replayed a few times too many at sleepovers.

Moreover, each of V/H/S/94’s segments was informed by actual historical events, from the Tonya Harding-Nancy Kerrigan assault and O.J. Simpson’s Bronco chase to the Waco siege and the Heaven’s Gate mass suicide. Discovering the ways these filmmakers play with that real-life context — and, more specifically, how pop culture has memorialized such events — is one surprisingly high-brow pleasure to be found amid the bloodletting.

Despite bright spots in the first two films, this franchise’s previous entries have fallen short of fully realizing the concept’s potential, neither engaging the aesthetic sensations of VHS nor leaning hard enough into the midnight madness these anthologies exude at their best. In that sense, V/H/S/94 is a screwy, gooey triumph.

V/H/S/94 is now streaming on Shudder.