How do Christmas cakes last for years? Inside the “perfect storm” of preservation

Love or hate them, there’s no denying some fruitcakes are not just old — they are ancient.

Fruitcake may never seem to go bad, but its reputation is rotten.

A mainstay of the holiday season, it is about as welcome in some houses as a lump of coal or a cousin’s unexpected (and uninvited) plus one. In the 1960s, former The Tonight Show host Johnny Carson became the unofficial figurehead of fruitcake phobia, joking: “The worst gift is a fruitcake. There is only one fruitcake in the entire world, and people keep sending it to each other, year after year.”

He kept up the act. In a 1985 stunt, a fruitcake was wheeled onto the show set on a forklift and broke Carson’s desk because it was so heavy. In 1989, he brought a demolition company into the studio to prove that even industrial machinery, sledgehammers, and explosives couldn’t penetrate the hard and seemingly indestructible fruitcake.

Did Carson have a personal problem with fruitcakes? Or did he merely say out loud what everyone else was thinking? That fruitcakes are tasteless, hard, stodgy, stale, inedible, and boring. Fruitcake defenders, meanwhile, insist that any taste and texture problems are the fault of poor preparation, not the cake. But love or hate them, there’s no denying some fruitcakes are not just old — they are ancient.

Not just for Christmas

Morgan Ford, seen here with Jay Leno in 2003 (who was not so anti-fruitcake, perhaps, as previous The Tonight Show host Carson), was then owner of the world’s oldest fruitcake.

In 1878 a woman named Fidelia Ford baked a fruitcake before tucking it away for the following year. But she died shortly after, and her family kept the uneaten fruitcake. It still exists today, making it the grand old age of 141. In photos shared in news reports by Ford’s great-great-granddaughter, the cake looks dry and lumpy but still surprisingly cake-like. Jay Leon ate a small piece on The Tonight Show in 2003 when the same cake was a sprightly 125.

Fidelia’s cake isn’t a one-off. Other centenarian fruitcakes exist, like one found in Antarctica, which is believed to be more than 100 years old and may have been left in a hut by British explorer Robert Falcon Scott during an expedition. Leno isn’t the only person to taste one, either. Others have devoured slices of decades-old cakes, and — last time we checked — they’ve survived to tell the tale.

This begs the question: How can fruitcakes last more than a lifetime while remaining (sort of) edible? And has the fruitcake always been such a contentious and condemned holiday treat?

Ancient trail mix

Sweet, fruit-laden buns and breads were Medieval analogues to the fruitcakes we know today.

“Fruitcakes are ancient,” Jeffrey Miller, an Associate Professor of Food Science and Human Nutrition at Colorado State University, specializing in food and culture, tells Inverse. “The Romans used them as a kind of trail mix for soldiers.”

Early recipes likely contained some combination of barley, honey, wine, pomegranate seeds, pine nuts and dried fruit, like raisins.

Miller explains that these early forms of fruitcake were helpful because they could be carried easily and were packed with calories — ideal for marching soldiers covering a lot of ground. They also, obviously, contained fruit.

“Fruit is highly seasonal, but if you candy it, you can make it last for months or even years,” Miller says.

This is the fruitcake’s superpower: It’s always had a long shelf life. Before modern preservation methods, this was incredibly important, enabling people to put fruits, nuts, and other tasty goodies gathered earlier in the year to use.

Spicy bread and celebratory cakes

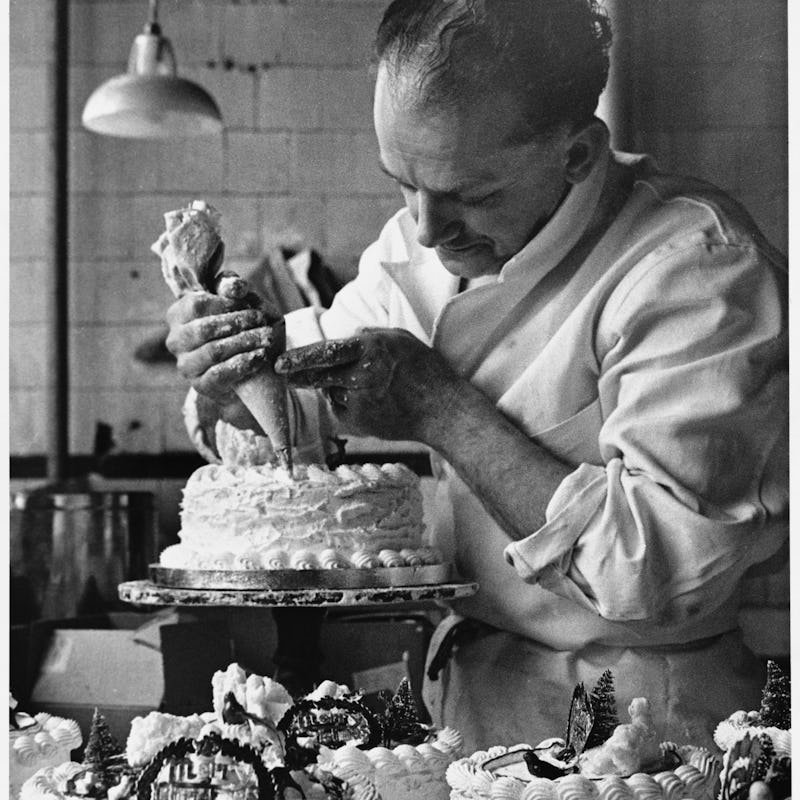

One heck of a fruitcake.

There are many more examples of early fruitcakes providing sustenance during extended travel periods — even crusaders in the Middle Ages reportedly relied on a similar kind of fruit and nut medley. But Miller tells us that the ingredients, mainly the candied fruit, would have been quite expensive and considered a luxury.

Annie Gray, a food historian and author of the book At Christmas we Feast, tells Inverse that yeasted doughs with similar ingredients were popular and prestigious during the Medieval period.

“These were full of rich flavors,” she says. “Spices, currents, dried fruits, things that were expensive and would last.”

It’s no surprise, then, that Gray says these breads were made for special occasions. “In Northern Europe, people would eat spice bread at celebrations, like christenings, funerals, Christmas, and weddings.”

During the 17th and 18th centuries, these fancy breads evolved into what we now think of as rich fruit cakes. “They were known as great cakes or plum cakes at the time,” Gray says. And they became particularly popular as wedding cakes.

One notable and rather extravagant example is the epic fruitcake served at Queen Victoria’s and Prince Albert’s wedding in 1840. This cake had three enormous tiers, measured more than 3 meters across, and weighed an astonishing 300 pounds. It was also lavishly decorated with royal icing — egg whites, sugar, lemon juice — and sugar paste figurines.

According to contemporary accounts, it was made from “the most exquisite compounds of all the rich things with which the most expensive cakes can be composed, mingled and mixed together into delightful harmony.”

Pieces of the cake were handed out as gifts to the guests. In 2016, a slice of the cake (176 years old at the time) fetched £1,500 (about $1,700) at an auction. Like Fidelia Ford’s cake, the slice doesn’t look all that appealing — but also doesn’t look like its pushing 200.

Fruitcake is still a popular type of wedding cake — both of the royal and regular varieties — in the U.K. and other Commonwealth countries today, like Canada and Australia.

Cake by mail

Perhaps try making your own fruitcake, instead of buying one at the store.

Over time, different countries have developed unique and regionally specific versions of fruitcake. But how do their recipes and traditions differ?

Although the U.K. and Commonwealth countries may rely on fruitcake for weddings, it’s “at the heart of Christmas,” Gray says. But it wasn’t always that way.

Instead, back in the 17th century, people ate a similar fruitcake on the Twelfth Night — a celebration to mark the end of the festive season that falls on January 5 or 6. As part of the celebrations, a bean and a pea were folded inside the cake. This was part of a fun, lottery-style game. Whoever got the bean in their cake slice was the king. Whoever got the pea was the queen — this is why the fruitcake was also sometimes called bean cake in historical records.

But Twelfth Cake — as it came to be known — fell out of fashion and became Christmas cake instead. Gray says we have the Victorians to thank for this shift.

“They got so obsessed with Christmas and so obsessed with Christmas Day,” she says. “Slowly, the cake became part of this overarching Christmassy tradition rather than Twelfth Night.”

Today, Christmas cake is dark, rich, moist, and decadent — often covered in a layer of marzipan and topped with a blanket of icing. Some take inspiration from Queen Victoria’s cake, adding decorations and dotting figurines on the top, like tiny snowmen or red-breasted robins.

“For the Brits, it’s a mark of Britishness to have these big punchy, fruity flavors,” Gray says. “The Christmas cake, the Christmas pudding, mince pies, all of that is incredibly British.” So why is fruitcake often considered dull, dry, and bland in the U.S.?

“Fruitcake is a perfect storm of pre-industrial revolution preservatives.”

Fruitcake traditions came to the U.S. from Europe back in the 18th century. But the fruitcake didn’t become popular in the States until the early 1900s. This was when companies began making, and shipping mail-order fruitcakes, giving people an easy way to send loved ones a gift during the holidays.

Although bakeries went to great lengths to ensure cakes tasted good after spending days or weeks in the mail, their mass production and long transit times may explain why fruitcakes gained a bad reputation. Especially considering it’s expected — almost a tradition in the U.S. — to regift fruitcakes many times over.

Another reason people may dislike them more in the U.S. is because of subtle differences in how they’re made. For starters, U.S. fruitcake tends to be a little lighter and drier. But they’re also packed with different fruits, like glace cherries, pineapples, and bits of melon. “In the U.S. version, there’s a lot more candied fruit,” Gray says. “This means more artificial colors and flavors, which some people find off-putting.”

But these aren’t the only fruitcakes to choose from. All over the world, there are riffs on the spiced bread and early fruitcake recipes of the past. “Italy has a Christmas fruitcake in the shape of a Panettone,” Gray says. And in Germany, you’ll find stollen, a sweet bread filled with dried fruit, nuts, and marzipan.

“You’ll also see fruitcake in some of the nations the British colonized,” Gray says. She points to Caribbean West Indian black bun or black cake as a great-tasting example.

“Raisins and other fruits are soaked in vast quantities of booze for years. Then they’re mashed up and put into a very rich, dark black cake, which is colored with burnt sugar,” she tells us. “It’s absolutely glorious, like eating solid rum.”

“That is what happens when you take the European — particularly British — tradition of fruitcake and throw it in with other wonderful ingredients and cultural influences,” Gray says.

The power of preservation

Trinidadian black cake is a dense, dark, rich fruitcake.

Although fruitcake recipes differ depending on where you are, the essential mix of sugar, low moisture ingredients, and alcohol tends to stay the same, making fruitcakes last an incredibly long time. “Fruitcake is a perfect storm of pre-industrial revolution preservatives,” Miller says.

Candied fruit is a crucial ingredient. These are small pieces of fruit, or fruit peel, soaked in sugar syrup. The syrup absorbs the moisture from the fruit, dries it out, and, as a result, preserves it. “All that sugar stops water activity, so it doesn’t really go bad,” Miller says.

Making the cake is only the first step. The next is “feeding” or “seasoning” the fruitcake. Holes are pricked into the top of the cake, and alcohol, like brandy, is poured inside or brushed onto its surface. People who take their fruitcake preparation seriously do this months — or even a whole year — ahead of time.

“Those old world-record fruitcakes are edible, in the larger sense of they won’t kill you if you eat them.”

“The ritual of making Christmas cake early in the year then ‘feeding’ it for months is part of the way some people lead up to Christmas,” Gray tells us. But she also warns that this ritual puts a lot of unnecessary pressure on people — especially women. “I'm not stopping anyone,” she says. “But we shouldn’t feel this is a thing we have to do.”

This sounds like a lot of hard work, so why bother? “Fruit cakes tend to be dry,” says Lilly D'‘ngelo, President of Global Food and Beverage Technology Associates, LLC, a consultancy firm helping companies introduce new food and beverage technologies. “Adding alcohol makes it moist, so it tastes better.” It also ensures the cake is soft and easy to cut. But, most importantly, it’s another way to ensure the fruitcake’s legendary shelf life.

"For yeast and mold to grow, they need both nutrients and water. In fruitcake ingredients, there are nutrients like sugar, starch, and protein. But there isn’t enough water for bacteria to grow,” D’Angelo says. “This is why fruitcake doesn’t go moldy.”

This lack of water and abundance of sugar and alcohol is why so many fruitcakes still exist — in some form — today, decades after they’ve been made. But although they may retain some of their shape and color surprisingly well, they won’t last forever. “Fruitcakes will eventually go moldy,” Miller says. “But not quickly, and if they’re prepared absolutely perfectly, they can last decades.”

Although he still wouldn't advise tucking into one. “Those old world-record fruitcakes are edible, in the larger sense of they won’t kill you if you eat them,” Miller says. “Though you really wouldn’t want to eat a fruitcake that is more than a year old.”

Fruitcake’s future

Fruitcake is less reviled by people in the U.K. and other parts of the world than in the U.S. However, Gray says the Christmas fruitcake isn’t as popular as it used to be, suggesting one reason could be the decadent ingredients.

“I think it’s those rich dark flavors,” she says. “And because they are heavy, people think they might not be good for them, which is causing a decline.”

Can we save the fruitcake? Maybe the answer is to experiment. Find the right fruitcake for you by borrowing recipes from other countries. Want something sweet and splendid? Try the U.K.’s hearty, juicy Christmas cake, and add those all-important layers of marzipan and icing. Fancy a decadent treat bursting with booze? Make the delicious and dark, rum-soaked black cake of the Caribbean. Need a lighter alternative? Try a fluffy, airy Italian Panettone.

This range of flavors, tastes, and textures proves there’s no right way to make fruitcake.

“What we have eaten at Christmas has changed so much throughout history,” Gray says. “Keep changing it, eat what you want, and spend the time how you want.”

TASTE OF THE HOLIDAYS is an INVERSE series about the science of food supported by Target. Get the inside scoop on your favorite (or hated) nostalgic holiday dishes via our hub, which will update with new stories through December 2022.

This article was originally published on