"Nature is being cut, rended, burned, despoiled — tortured by a thousand cuts."

A rapidly declining insect population spells trouble for humans

A special publication gives us a new reason to think about how human-driven climate change and environmental damage has affected the world's insect population.

by Tara YarlagaddaApart from bug-loving entomologists and innovative roboticists, most humans regard insects with a mixture of disdain and disgust.

Our aversion to insects means we neglect to consider these tiny critters' fate in the climate crisis. Instead, we give attention to starving polar bears and other awe-inspiring megafauna affected by environmental disasters.

They are deserving of it, but a special publication in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences gives us a new reason to think about how human-driven climate change and environmental damage has affected the world's insect population.

Hailing from a variety of scholarly backgrounds, the experts on the issue's 12 papers all share one thing in common: growing concern over insect biodiversity, which is declining in some populations at an alarming rate of 1-2 percent each year.

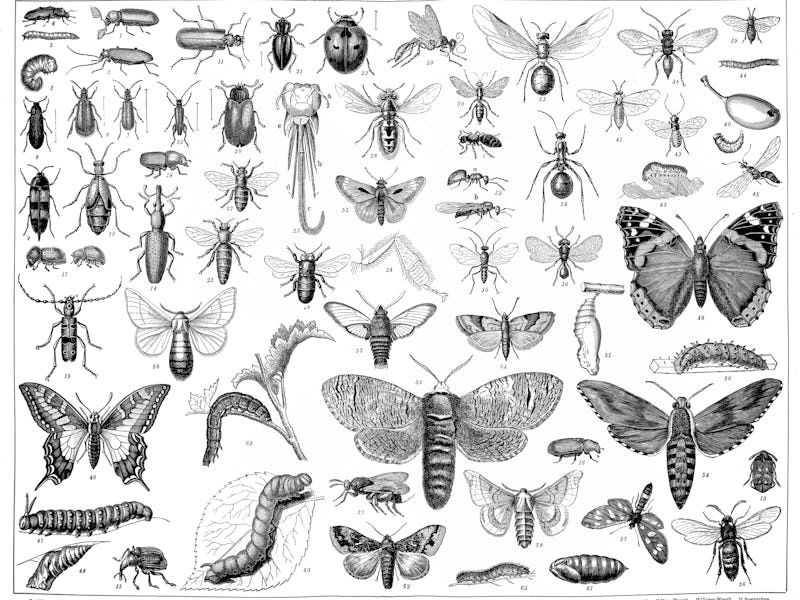

A figure from a study in the special publication, showing insects that are beneficial to humans.

What's new — In his introduction to this special feature, David Wagner, a professor of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at the University of Connecticut, summarizes the "insect apocalypse" in a simple statement: "Nature is under siege."

No surprise: humans are to blame, largely due to our growing population, which has rapidly exploited Earth's natural resources, used up nearly all arable land for agriculture, and pushed the planet to the brink with the climate crisis.

"It is clear that 7.8 billion [people] are already using more resources annually than the world can yield annually," Wagner tells Inverse. "Nature is being cut, rended, burned, despoiled—tortured by a thousand cuts."

Wagner calls out three factors that have particularly contributed to the insect's decline:

- Climate change

- Habitat loss

- Degradation

Wagner focuses particularly on the role our lavish lifestyles in the developed world have played in contributing to agricultural intensification:

"Overconsumption demands greater agricultural production--achieved by increasing yields, industrializing agriculture, increasing pesticide usage, manufacturing and adding unprecedented amount of nitrogen to the earth’s geological nitrogen budget, and, worst, deforesting the planet to make yet more croplands."

Increased agricultural activity since World War II can be directly linked to insect biodiversity loss, accord to Wagner.

"Agriculture threatens insects and nature on many axes: foremost through loss of habitat, but also by exacerbating global warming, elevating exposure to pesticides, nitrification of lands and waters that have been geologically nitrogen limited, and more," Wagner says.

"Climate change, unlike most other anthropogenic stressors, has the potential to drive extinction far from sites of human activity."

These agricultural "megafarms" also make it difficult for even the tiniest creature — like an insect — to pass over them, further limiting the natural habitat of bugs, according to Wagner.

A never-ending boom of agricultural growth has also contributed to the other big issue decimating insects: climate change.

"Moreover, agricultural expansion, further exacerbates global climate change by destroying carbon sinks — forests, especially in the tropics — agriculture, and especially livestock," Wagner says.

Wagner notes that these activities generate enormous quantities of methane, which he calls "one of the most ominous of the greenhouse gasses."

These climate change impacts are most devastating to insects in certain places, such as the tropics.

Wagner adds, "One of the most important themes or questions that came out of the 12-paper PNAS collection is that the impacts of climate change could be much greater than previously recognized: in tropical forests, cloud forests, mountains, and other fragile communities."

A figure illustrating insect diversity from Wagner's introduction.

Digging into the details — The feature publication presents a variety of perspectives on insect biodiversity, though not all of them are in agreement on the specifics of insect population trends.

For example, not all insects are in decline everywhere. A study from Puerto Rico, led by Timothy D. Schowalter and colleagues, directly challenges previous research that indicated a devastating loss of insects in the region. Furthermore, the scientists found that frequent storm systems, rather than global warming, affected insect populations in Puerto Rico.

Plus, plenty of bugs are doing just fine during the apocalypse. The tenacious cockroach will probably be A-OK, much to the disappointment of homeowners and renters everywhere.

"Bed bugs and some cockroaches will do just fine and likely increase in our cities," Wagner says. He adds that as the planet warms, insects may expand their natural ranges and increase in places that have become more habitable, such as the Arctic.

"No matter what we do to the planet, there will be insect winners and losers… but [the] number of losers are increasing at an unacceptable and unprecedented rate," Wagner says. "My guess, is that future generations will look back at our time, and regard our actions — and inactions — with great disapproval and dismay."

Although the special publication notes that insect populations are most in decline in "areas of high human activity," the biodiversity loss has been recorded all around the globe.

"Climate change, unlike most other anthropogenic stressors, has the potential to drive extinction far from sites of human activity, deep into mountainous regions, rainforests, badlands, and other wild places," Wagner says.

It's clear that more data is needed so we can paint a more complete picture of insect biodiversity loss around the globe.

"There are still too little data to know how the steep insect declines reported for western Europe and California’s Central Valley—areas of high human density and activity—compare to population trends in sparsely populated regions and wildlands," writes Wagner in his introduction.

But some scientists are working to tackle that data problem. A study by two 'insectometers," Daniel Janzen and Winnie Hallwachs, represents a bold move by Costa Rica to create a biological inventory of insects, which could help with species conservation.

An illustration of the 'death by a thousand cuts' on insect populations.

Why it matters — From the special publication, we can learn that biodiversity loss has hit some insect species harder than others.

"The species that are being lost at the greatest clip tend to [be] the bigger species, more specialized species, those with complex species. These are being replaced with the weedy, generalized, and plebeian species," Wagner says.

These specialized species perform unique roles in different ecosystems, so their loss is a significant blow that has huge ripple effects for other species — including humans. Insects provide many essential functions that are vital to human life, including fruit and vegetable pollination; decomposition of leaves and wood; and pest control on crop plants.

"Insects tether together our terrestrial ad freshwater ecosystems," Wagner says. These tiny bugs comprise "the stuff of food webs—the very fabric of nature," according to Wagner.

Therefore insect biodiversity loss is directly intertwined with human existence. A UN report concluded that biodiversity loss is as significant a problem for humans as climate change.

What's next — The studies have far-reaching implications for tackling the climate crisis, since global warming directly contributes to declining insect populations.

The clock is increasingly running out on climate change, according to Wagner, but we can still make an impact if we act decisively.

"We must find ways to mitigate our collective impacts, reduce consumption, and learn to live sustainably," Wagner says.

In a study led by Akito Kawahara, researchers provide eight straightforward ways that individuals can tackle the insect biodiversity crisis, ranging from reducing pesticide use to growing more native plants.

But, ultimately, Wagner suggests that we must think bigger and tackle systemic issues that contribute to climate change.

"The personal and collective actions of individuals, communities, and nations, i.e., how we choose to live, can also help society to close the gap, between what we use and nature can provide, and to help build a just and sustainable future, one where we are using and exploiting nature at a rate where she has time to heal, maintain, and flourish."

Summary: The 11 papers in this collection examine insect decline from geographic, ecological, sociological, and taxonomic perspectives; evaluate principal threats; delve into how the general public perceives news of insect declines; and offer opinions on actions that can betaken to protect insects. Insect declines have been the focus of a range of popular media, with widely varying levels of accuracy. Consequently, a core intention of this special issue is to provide a scientifically grounded assessment of insect population trends; contributors were urged to provide critical evaluations of raw data, published studies, and reviews, given that a few of the more highly publicized reports of insect decline suffered from unjustified assumptions, analytic issues, or over extrapolation. For example, Willig et al. (23) and Schowalteret al. (24) provide data that insect numbers have not generally declined in Puerto Rico’s Luquillo Forest, directly contradictingLister and Garcia’s (25) claims of catastrophic collapse of the insect fauna, with linked effects to the forest’s amphibian, reptile, and bird fauna. Hallmann et al. (26) model relationships among insect biomass, abundance, and diversity of hover flies, and explore how these measures interrelate in empirical and theoretical contexts.Many of the 11 contributions end with prospective elements that draw attention to data gaps, make methodological recommendations, and point to specific actions that may help insect populations and species survive (27–29).

This article was originally published on