Discovery of ancient stone tool rewrites early human history

Study takes a look at the Iberian Peninsula some 40,000 years ago.

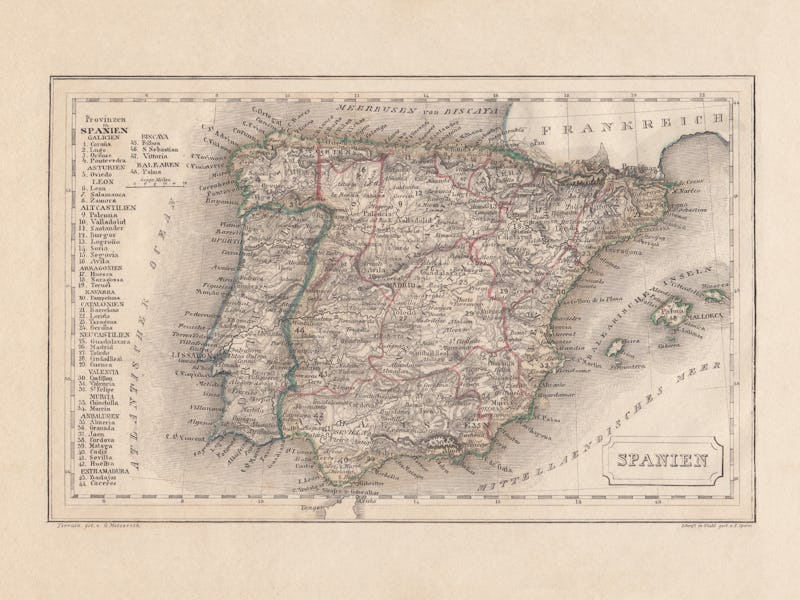

As early humans spread across the planet absorbing and replacing other hominids in their wake, Neanderthals tried to hold out in a corner of westernmost Europe — the Iberian Peninsula.

Now composed of Spain and Portugal, the Peninsula is considered the site of Neanderthals' last stand before humans took over. But contrary to past research findings, the domination of Neanderthals in Iberia began far earlier than scientists had thought.

A study reveals that humans occupied present-day central Portugal some 5,000 years ahead of the timeline researchers had previously established. The new chronology is based on the surprise discovery of stone tools used by modern humans in a cave near the Atlantic Ocean.

The cave, called Lapa do Picareiro, contained stone tools used for hunting and cooking, similar to those discovered at other sites across Eurasia.

Artifacts found in Portuguese caves put humans in the area far earlier than previously thought, a new study finds.

The findings change researchers' understanding about the spread of modern humans — they also reveal the influence of climate change and other environmental factors on our species' movement through Europe.

Rewriting history — Past estimates pinned modern humans' arrival in the northern part of the Iberian peninsula to 43,300 to 40,500 years ago. Researchers believed the occupation of southern and western Iberia happened about 6,000 to 12,000 years later, stalled by the significant Neanderthal populations living there.

The new study identifies human artifacts in central Portugal dating back between 41,100 and 38,100 years. That suggests several things:

- Humans were likely present in the region much earlier than previously understood

- Neanderthal populations would have been more sparse than researchers thought

- Modern humans spread rapidly into southern Europe

- Humans and Neanderthals did not have a natural border between them

The findings were published on Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Researchers excavating at Portugal's Lapa do Picareiro.

Unimpeded dispersal — Filling in the details of early humans' spread across Europe, the study challenges the old belief that Neanderthals staved off humans' march westward.

Rather, the new study shows, humans enjoyed an "unimpeded dispersal" across western Eurasia. And for perhaps thousands of years, modern humans and Neanderthals overlapped.

We know from previous studies that ancient humans and Neanderthals interbred. In fact, one finding suggests all living humans have a bit of Neanderthal DNA — the result of their populations coming into contact as Homo sapiens spread across the globe.

Still, on the Iberian Peninsula, the researchers had not yet found good evidence of contact — sharing tools, for instance — between groups of humans and Neanderthals.

Researchers excavating at Portugal's Lapa do Picareiro.

Climate clues — The new findings also "support the notion that climate and environmental change played a significant role" in human migration, the study authors write.

Cold and dry periods may have led to decreased Neanderthal populations, making space for the incoming humans. As a result, modern humans dispersed in a "mosaic" pattern as they replaced Neanderthal populations, the researchers say.

As our understanding of our own species' history shifts, the picture of how humanity came to be becomes a bit more clear. But the picture is far from finished, Jonathan Haws, lead study author and professor at the University of Louisville, said in a statement.

"I've been excavating at Picareiro for 25 years and just when you start to think it might be done giving up its secrets, a new surprise gets unearthed," Haws said. "Every few years something remarkable turns up and we keep digging."

Abstract: Documenting the first appearance of modern humans in a given region is key to understanding the dispersal process and the replacement or assimilation of indigenous human populations such as the Neanderthals. The Iberian Peninsula was the last refuge of Neanderthal populations as modern humans advanced across Eurasia. Here we present evidence of an early Aurignacian occupation at Lapa do Picareiro in central Portugal. Diagnostic artifacts were found in a sealed stratigraphic layer dated 41.1 to 38.1 ka cal BP, documenting a modern human presence on the western margin of Iberia ∼5,000 years earlier than previously known. The data indicate a rapid modern human dispersal across southern Europe, reaching the westernmost edge where Neanderthals were thought to persist. The results support the notion of a mosaic process of modern human dispersal and replacement of indigenous Neanderthal populations.