A plant scientist’s guide to keeping your jack-o’-lantern from rotting before Halloween

Pumpkins spend most of their lives in fields, developing on top of soil that teems with fungi, bacteria, water molds, and other microbes.

For many Americans, pumpkins mean that fall is here. In anticipation, coffee shops, restaurants, and grocery stores start their pumpkin flavor promotions in late August, a month before autumn officially begins. And shoppers start buying fresh decorative winter produce, such as pumpkins and turban squash, in the hot, sultry days of late summer.

But these fruits — yes, botanically, pumpkins and squash are fruits — don’t last forever. And they may not even make it to Halloween if you buy and carve them too early.

As a plant pathologist, gardener, and self-described pumpkin fanatic, I have both boldly succeeded and miserably failed at growing, properly carving, and keeping these iconic winter squash in their prime through the end of October. Here are some tips that can help your epic carving outlast the Day of the Dead.

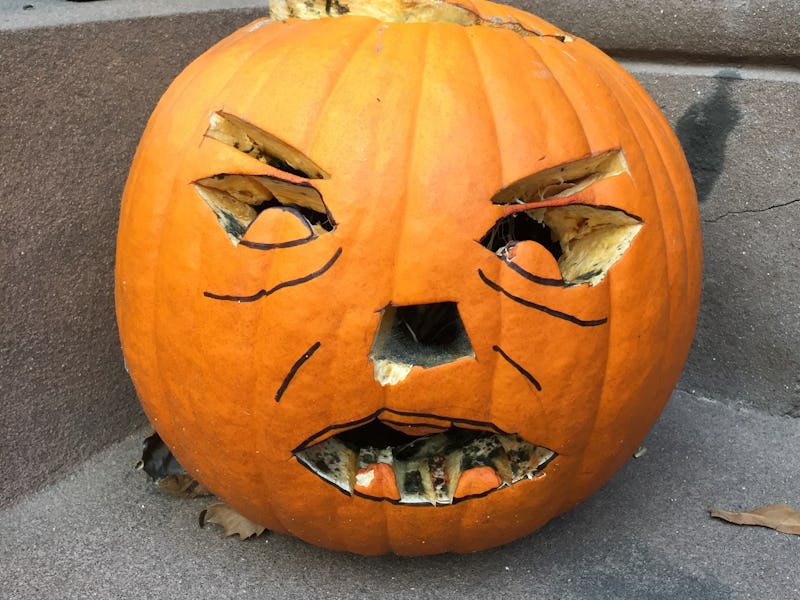

A bruise or crack will allow opportunistic fungi, bacteria, water molds, and small insects to invade and colonize your pumpkins. Keeping the rind defect-free and the stem intact ensures your prized pumpkin has a longer shelf life.

Pick a healthy pumpkin and transport it carefully

This may seem obvious but shop for a pumpkin in the same way that you shop the produce aisle. Whether you plan to carve them or not, choose pumpkins that are not damaged, dented, or diseased. Is the stem loose? Is there a clear break in the rind? Are there any water-soaked spots on the exterior?

Post-harvest diseases — those that occur after the pumpkin is removed from the vine — can happen anywhere between the field where they were grown and your front step. A bruise or crack will allow opportunistic fungi, bacteria, water molds, and small insects to invade and colonize your pumpkins. Keeping the rind defect-free and the stem intact ensures your prized pumpkin has a longer shelf life.

The trip home also matters. Most of us transport pets, kids, muddy hiking boots, and food in our cars, which makes our vehicles giant Petri dishes harboring common environmental molds and bacteria. Some of those microbes could colonize your unsuspecting pumpkins.

Secure your pumpkins en route to your house, so they don’t suffer bruising or stem breakage. My family often uses seat belts to protect ours. Once home, don’t carry your pumpkin by the stem, which can lead to breakage, especially if it is big and heavy.

Keep them clean and dry

Pumpkins spend most of their lives in fields, developing on top of soil that teems with fungi, bacteria, water molds, and soil-dwelling animals like nematodes, insects, and mites. Removing these organisms, and any eggs they may have affixed to your pumpkin’s rind will help preserve it.

To get rid of them, wipe down your pumpkins, preferably with a bleach wipe. This is especially important if you plan to carve them: Piercing the dirty rind with a sharp tool will introduce these eager visitors deeper into the heart of your pumpkin. Be sure to use clean tools as well. Microbes can reside and multiply on small amounts of pumpkin debris stuck in the teeth of dirty carving knives.

Even if you are not carving your pumpkin, wiping it down isn’t a bad idea, since it may have small bruises or cracks that are easy to overlook.

Hollow pumpkins out thoroughly, but don’t overdo it

Much of the work of carving a pumpkin involves separating the fibrous strands and seeds inside it from the harder pulp that makes up the pumpkin’s walls. As you scoop out the pumpkin’s innards, thoroughly inspect the inside walls for soft rotten patches or dark tissues, which may have been colonized pre- or post-harvest by bacteria, fungi, or water molds. Diseased pumpkins sometimes produce an off-putting smell, so use your nose as well.

If you find these issues as you carve, you may want to try carving another pumpkin. You can also paint your pumpkins instead of carving them, which averts the need to peer inside.

Some online tutorials and YouTube videos recommend thinning out pumpkins’ walls to better allow candles or LED light to pass through. But if you make the walls too thin, your jack-o’-lantern’s fangs will become inward-curving skin tabs as the pulp desiccates and deforms. A toothless jack-o’-lantern scares no one.

Another advantage of maintaining thicker walls is that it enables you to try 3D carving. This involves shaping the pumpkin’s surface as you would carve a piece of wood without breaking through the shell, and can produce dramatic results.

Some people soak their carved pumpkins in diluted bleach or vinegar water after completing them. But this technique is a double-edged sword: Adding more free moisture to your masterpiece invites windblown mold spores and rain-splashed bacteria to colonize it. However, applying a light coating of petroleum jelly or vegetable oil to all the exposed parts can extend the shelf life of your sculpted squash.

Protect your creation

October is a wet month with frequent rains in many parts of the U.S. Rain falling on your jack-o’-lantern will invite every mold in the neighborhood to take up residency in or on it. For this reason, I recommend keeping your pumpkins on a covered porch or displaying them from indoors in a window.

It’s OK if some mold forms inside it, as not all fungi cause soft rots – diseases that produce wet spots that spread, become mushy, and turn black. If a pumpkin does become overly moldy on the inside walls, move it outdoors to avoid producing a lot of spores in your home.

When your pumpkin does start to mold and collapse, don’t throw it in a landfill. Put it out for your neighborhood deer or atop your compost pile. Or find a spot in your yard where you can watch it degrade over time until it turns back to soil in time for next year’s pumpkin patch.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Matt Kasson at West Virginia University. Read the original article here.