Will NASA’s Europa Clipper Really Find Aliens? Here’s What the Spacecraft Can and Can’t Do

What could be lurking under Europa’s icy shell?

The idea that extraterrestrial life could exist in our Solar System got one of its earliest boosts almost half a century ago when NASA spacecraft first photographed the more intricate details of Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa.

The Voyager 2 mission captured a puzzlingly smooth surface in July 1979. It also found what astronomers have dubbed “crop circles.” On Earth, people attribute supernatural forces or alien visitors to these mysterious patterns formed from depressions in a field of wheat. But “crop circles” is also a name astronomers have given the puzzling, faint troughs on Europa’s surface. No, scientists don’t think they were made by intelligent alien life, but they do think they could be a sign that Europa might have the right ingredients to support life. If surface ice were moving around, it would create these troughs. And that morphing ice would exist because of hydrothermal activity, which could theoretically support life.

Europa’s crop circles will be better understood (hopefully) when Europa Clipper, NASA’s largest planetary mission in its 66-year history, completes the 1.8 billion mile trek through space that it began on Monday. Its mission will attempt to answer one of NASA's most ambitious questions: Are we alone in the universe?

A mosaic of Europa from Voyager 2’s approach in 1979. One instance of a crop circle is visible here. Find the diamond-shaped mark just below the middle of the moon’s visible surface. Then look to the right, close to the shadow. A dark line travels up from the shadow, towards the left, and continues up with fainter coloring.

Will Clipper find life on Europa?

For one, astrobiologists need to make sure Europa has plumes, which are vents of water and other material erupting out from beneath the surface. Confirmed plumes would be a sign that Europa is a geologically-active celestial body that is churning around heat and chemical ingredients that are known to be key to life. Clipper will also act as reconnaissance to spot a promising landing site for a potential future spacecraft.

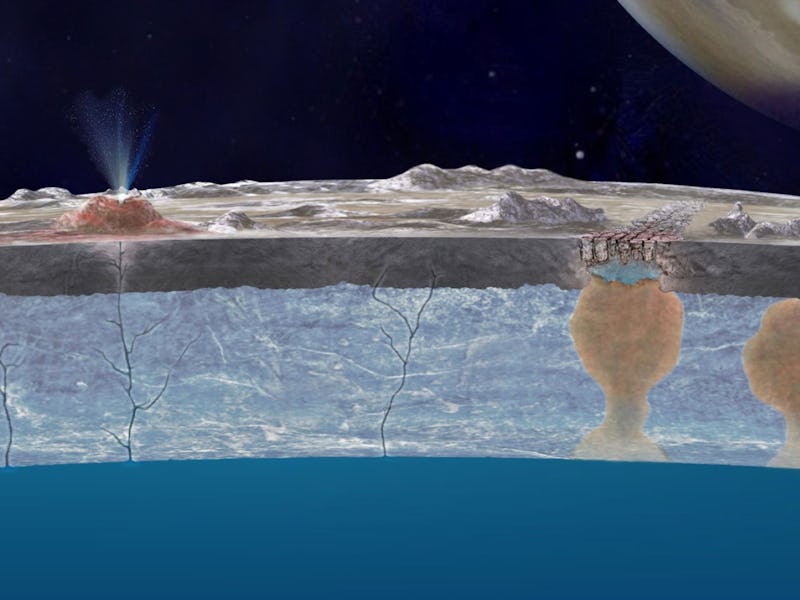

It’s part of NASA’s hunt for signs that this icy moon is habitable to life. Based on brief visits from NASA missions like Voyager 2, Galileo, New Horizons, and Juno, researchers think Europa is covered in a 15-mile-thick shell of ice. But despite the ice’s fragility, the surface has remarkably few large craters. This points to the possibility that Europa is actively regenerating ice from a global subsurface ocean.

“Traces of what we call crop circles could be the sign of the ice shell moving,” Ines Belgacem, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said during a session on October 8 at the 56th Annual Meeting of the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences in Boise, Idaho.

NASA’s Juno spacecraft took the data that became this composite image of Europa on September 29, 2022. Note how few craters appear on Europa’s surface.

And, if hydrothermal activity under Europa’s surface punches through its shell, Clipper’s suite of instruments may get a peek of the potentially life-supporting chemicals that lie beneath.

Under the surface is where life would be: Europa’s exterior is too harsh a place. Below the ice, alien life might have both shelter and warmth. Jupiter has almost three times more surface gravity than Earth, and the gas giant is more than twice as massive as all the other Solar System planets combined. More mass means more gravity; and Jupiter’s powerful gravity tugs at Europa mightily. The moon’s elliptical orbit adds to the existing stress, promoting uneven pressures during orbit. This physical tension might be causing heat to be released on the seafloor of Europa’s ocean.

If chemical compounds exist in this water, whether generated on-site, or carried over from volcanic moon Io and made their way to the subsurface thanks to the dynamics of the ice, nutrients for life might be swimming in the ocean.

Clipper will perform 49 flybys of Europa starting in 2031. Some of these may become “recon-able” flybys, Belgacem said, where the spacecraft would target regions with crop circles to see if they’re good places for a future lander to further probe the questions about habitability.

After analyzing Clipper’s flight plan, Belgacem and colleagues have an early idea about what these landing-site-scouting flybys require. That may change as the mission progresses. For now, the crop circle region must be on Europa’s dayside during the flyby. Altitude is also important. “We need to have an altitude that's sufficient for high resolution, but also not so low that we wouldn't be able to take good images,” Belgacem said. Shadows are another consideration. “The idea is you don't want too much shadow because you wouldn't see anything, and you don't want too few shadows because you need to assess the topography.”

Belgacem added that so far, 12 of the currently-planned 49 flybys are planned to scout for future landing sites.

Plumes, if they are there, would be a thrilling discovery. Another ice-shelled moon of the outer Solar System, Enceladus, stunned NASA’s Cassini mission team when the Saturn world revealed a magnificent jet to the spacecraft in 2005. The Hubble Space Telescope found evidence of “suspected plumes of water” on Europa in 2014. But they haven’t been confirmed.

Once Europa Clipper begins its investigations next decade, humanity will come one step closer to learning if life exists in Jupiter’s shadow.