Astronomers Discovered the Biggest Pair of Black Hole Jets Ever, and It's the Stuff of Cosmic Horror

They've nicknamed the system Porphyrion, after a rebellious giant in Greek mythology, and the name fits.

Imagine an amoeba blasting out jets of energy that stretched the width of the Earth. That’s what’s happening about 7.5 billion light years away on a much larger scale, where a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy is blasting jets of high-speed particles and energy across 23 million light years of space. That’s about 140 times the width of our Milky Way galaxy. It’s the longest pair of black hole jets ever discovered so far, and it could shed light on how supermassive black holes have sculpted not just their host galaxies, but the largest structures in the universe.

Caltech astrophysicist Martijn Oei and his colleagues published their work in the journal Nature.

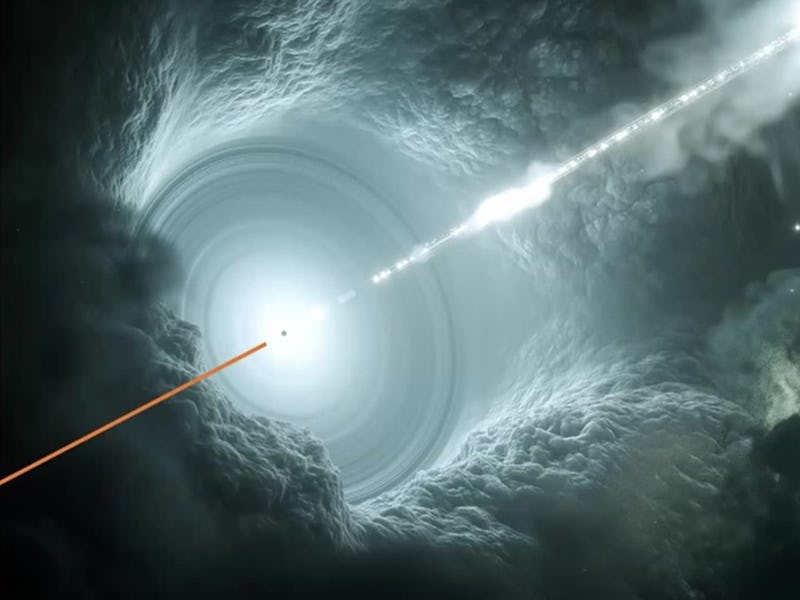

This artist’s illustration shows what one of Porphyrion’s jets might look like close to its source; the orange arrow on the left points to the supermassive black hole itself.

Meet a Cosmic Monster: Porphyrion

Oei and his colleagues used the Low Frequency Array — a sprawling network of radio dishes spread across 8 European countries — to scan a swath of the sky for long, rolling radio waves from supermassive black holes feasting on the entrails of their host galaxies. They found more than 8,000 pairs of what astronomers call relativistic jets: beams of energy and high-speed charged particles spewing outward from the poles of a supermassive black hole. And one monster pair of relativistic jets has a combined wingspan of about 23 million light years.

“The Milky Way would be a little dot in those two giant eruptions.”

In other words, one black hole is continuously erupting energy and plasma into space across a distance more than 140 times longer than our whole galaxy, and it’s carrying the power of trillions of stars. Oei and his colleagues nicknamed the pair Porphyrion.

“The Milky Way would be a little dot in those two giant eruptions,” says Oei in a statement.

The team of astrophysicists used a gaggle of other telescopes — the Giant Meterwave Radio Telescope in India, an instrument at the Kitts Peak Observatory in Arizona, and the Keck Observatory in Hawaii — to pinpoint the source of the massive jets. They also used the jets’ mass and energy to calculate how much matter the black hole had already “eaten.” It turns out that the supermassive black hole erupting these gargantuan jets is more than a billion billion (a quintillion, if you’re feeling fancy) times the mass of our Sun, and it’s busily feasting on gas and stars at the heart of a galaxy ten times the mass of our own, about 7.5 billion light years away, and halfway across the universe.

Supermassive black holes are voracious but messy eaters. As material spirals into the black hole, it releases energy, and some of that energy powers twin jets that fling gas out into space in opposite directions at nearly a quarter of the speed of light. A tremendous amount of energy, in every wavelength from radio waves to gamma rays, goes along with it.

According to Oei and his colleagues’ calculations, Porphyrion must have been tossing parts of its meal aside in its huge jets for about a billion years in order to create the giant, cosmos-spanning eruptions of energy and charged particles that astronomers see today.

“All of these jets start small, and they grow with time,” says University of Hertfordshire astronomer Martin Hardcastle, a coauthor of the recent study, in a press conference. “The more powerful the jet is, the faster it’s going to expand. That strong power together with that long amount of time set the length of the jet system.”

And Porphyrion’s wings stretch wide enough to cut across the vast structures that make up the scaffolding of the universe itself.

This artist’s illustration shows what Porphyrion looks like in relation to the large-scale structure of the universe around it; the filaments of light are made up of galaxies strung together by gravity.

Magnetizing the Scaffolding of the Universe?

As a supermassive black hole’s jets blast outward into space, they carry charged particles, energy, and magnetic fields along with them. All of those things have an impact on the space they pass through. Physicists already know that a black hole’s jets can shape how its host galaxy evolves, and even impact the intergalactic neighborhood nearby.

Now Porphyrion shows that the largest and most powerful jets may have enough reach to influence the large-scale structure of the universe itself: the cosmic web, which is a network of filaments that galaxies and galaxy clusters are arrayed along, with huge voids in between. Porphyrion’s jets reach about a third of the way across its nearest cosmic void. And that makes Oei and his colleagues think that supermassive black holes with tremendous jets like Porphyrion might affect the large-scale fabric of the universe, especially by spreading magnetic fields into surrounding voids and filaments.

That’s especially true because the universe is expanding. Six billion light years ago, when the radio waves Oei and his colleagues observed originally left Porphyrion, the universe was a much smaller place, which means giant relativistic jets would have been able to punch above even their tremendous size. Meanwhile, the magnetic properties of the cosmic web affect galaxies, the stars within those galaxies, and the planets orbiting those stars.

“Small things and large things in the universe are intimately connected,” Oei said during a recent press conference.

What’s Next?

Oei and his colleagues hope to understand more about how that process happens, which means they’re going to need to find a lot more cosmic monsters like Porphyrion.

So far the LOFAR survey has only covered about 15 percent of the sky, but it’s continuing to search. Oei and his colleagues say their 8,000 giant pairs of relativistic jets, including Porphyrion, are “just the tip of the iceberg. The team estimates that there could be at least 100,000, and up to a million, more of these gargantuan jet systems out there in the relatively nearby universe.

"They are really interesting in themselves,” says Hardcastle. “Who doesn't like giant jets coming out of black holes?"