An ancient case of mistaken identity reveals a strange amphibian

You won't be able to keep up with the twists and turns in this story.

Conducting scientific research can often feel like taking part in a detective mystery. You spent so much time hunt for evidence, dodging red herrings, and devising theories, only to realize that your deductions were wrong.

Then, suddenly, a new clue manifests as if out of thin air, leading you down a new, long, winding road to discover the true culprit at the heart of your scientific mystery.

That's exactly what happened earlier this year, when a team of scientific researchers found themselves investigating an ancient case of mistaken identity — one which led to a surprising amphibian culprit.

INVERSE IS COUNTING DOWN THE 20 MOST WTF SCIENCE STORIES OF 2020. THIS IS NUMBER 3. SEE THE FULL LIST HERE.

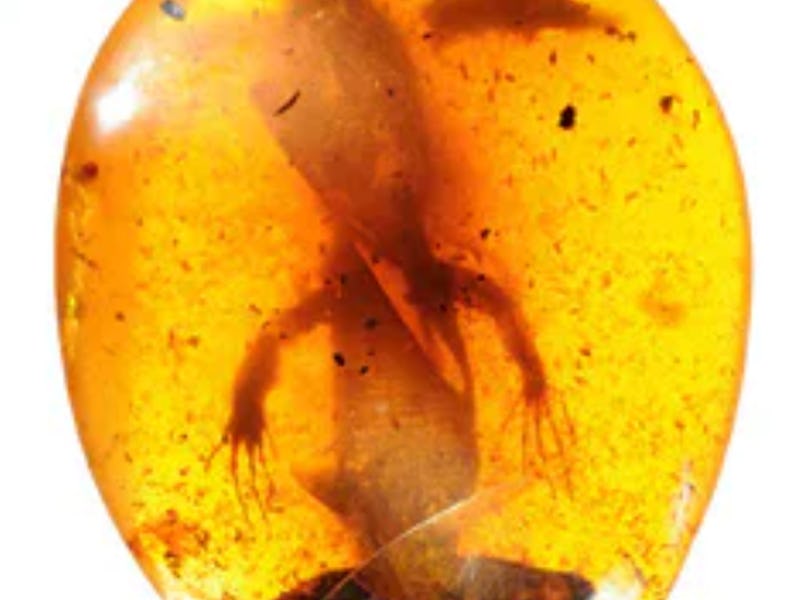

An image of the fossils from the 2016 paper.

In 2016, Juan Diego Daza and his colleagues announced a discovery any paleontologist could be proud of: A 99-million-year-old chameleon, preserved in amber. Daza is an assistant professor of Biological Sciences at Sam Houston State University and was the lead author on the 2016 study detailing the fossil find.

But not long after the announcement, Daza got a call from fellow paleontologist Susan Evans that would change everything.

The mysterious creature they had found was not, in fact, a chameleon, Evans suggested. Rather, it was a strange, ancient amphibian known as and albanerpetontid, though some researchers give it the nickname "Albie."

"The albanerpetontids — they’re very unusual amphibians," Daza told Inverse at the time. "In a way, the body shape is similar to a salamander in the sense that they have four legs. And they have a tail — something that other amphibians that are alive today [don’t have]."

But the researchers needed more evidence than Evans' word. In another stroke of luck, Daza received an email from gemologist Adolf Peretti that would lead to the confirmation of the albie's identity.

Peretti had a collection of 60 vertebrate fossils from Myanmar, where Daza found his specimen. At Daza's suggestion, Peretti conducted a CT scan of his collection.

A modern chameleon uses its tongue to snatch prey — not unlike the ancient albie.

Lo and behold: Peretti had an adult albie fossil in his collection. Daza and researchers compared their specimen to Peretti's, confirming that what they had found in 2016 was indeed an albie — not a chameleon as previously thought.

Daza and his colleagues released an updated research paper describing their mistake in November of this year in the journal Science.

It's easy to see how the mistake was made. Albies sported claws and scales that more closely resembled reptilian features rather than amphibians.

Plus, the albie had a wicked cool slingshot tongue it used to ensnare prey, similar to modern chameleons. With this finding, Daza and his team may have confirmed the oldest projectile tongue ever discovered in nature.

Here's how it works:

"They remain steady until a prey approaches and when the prey is in the range of their tongue, they will shoot at the tongue quickly. And, usually, the tongue is sticky at the end. And that allows them to engulf the prey and drag it to their mouths," Daza says.

INVERSE IS COUNTING DOWN THE 20 STORIES THAT MADE US SAY 'WTF' IN 2020. THIS IS NUMBER 3. READ THE ORIGINAL STORY HERE.

This article was originally published on