The most misunderstood part of intermittent fasting isn’t what you think

Humans can’t stick to the same schedules as mice — or get the same results.

If only we could wake up with the Sun, run ten miles every day, eat five servings of vegetables, cut out sugar-sweetened beverages, and practice mindfulness for the rest of our days. Surely, or so science shows, we’d improve our cardiovascular health, ward off depression, and dramatically extend our lifespan.

The only problem with this science-backed roadmap to a healthier, longer, happier life? We’re human.

That crucial detail can sometimes get lost in the buzz around the popular diet regime intermittent fasting. The casual reader can get swept up in the transformative results promised to them by a headline on an animal study, or conflate one form of timed eating with another. But one of the biggest issues is more to do with how well we stick to anything.

Compliance with timed eating regimens, experts say, can be a sticking point when managing expectations for a diet change.

Krista Varady, who researches intermittent fasting and is a professor of kinesiology and nutrition at the University of Chicago, Illinois, tells Inverse that “humans have a hard time following these diets perfectly.” But “the animals are kind of just forced to follow them perfectly.”

What does “intermittent fasting” mean?

Intermittent fasting can mean many different things. People say “intermittent fasting” when they talk about restricting eating to 12 hours of the day, fasting on a few days of the week, or even every other day. Technically, we all fast “intermittently” every night when we go to sleep.

“The misconception is about the words ‘intermittent fasting’,” Valter Longo tells Inverse. “Of course, we eat. It depends what we eat, how much we eat. Intermittent fasting is the same way — it doesn’t mean anything. I wish people just stop using it and turn to, ‘what are we talking about?’”

Longo, who is referred to as the “godfather of fasting”, has researched intermittent fasting for decades and is a professor of gerontology and biological sciences at the University of Southern California, where he directs their Longevity Institute.

Generally, there are some loosely-defined regimes that come under the intermittent fasting umbrella:

- Time-restricted eating or feeding: This includes the popular 16:8 diet — eat during 8 hours, “fast” for the other 16, or even 12 hours to eat, and 12 to “fast.”

- Alternate-day fasting: Abstaining from eating every other day.

- Extended fasts: Fasting for 24 or more hours, every week or every month.

- Fasting “mimicking” diets: This is a diet that recreates the conditions of a fast, like the meal kits Longo sells, which are low-calorie, low-protein foods.

In animal studies, the methods that produce the most profound health benefits aren’t ones that we humans can successfully stick to. In turn, results from these studies can give people unrealistic expectations for their own fasting plans.

In human studies, both the fasting regimes and the benefits are often more tempered. Experts say the benefits of an intermittent fasting regimen hinge on which one you follow and are able to comply with.

What the animal studies show — Studies on intermittent fasting in animals have some dramatic outcomes.

In one of the earliest studies on intermittent fasting, rats put on an alternate-day fast increased their lifespan by an average of around 80 percent. Feeding mice every other day led to better glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, markers of type-2 diabetes. Alternate-day fasting in mice reduced the incidence of lymphoma. Mice on a very low calorie, low protein, “fasting-mimicking diet” experienced a delayed onset of cancer, reduced markers of inflammation, and improved memory and cognition.

Varady says dramatic results like these can create inflated expectations in people who hear about them.

“Rodent models of fasting don’t really translate,” she said. “Even all the cardiometabolic benefits, like the lipid-lowering, and all the diabetes remission people see in rodents — we see it a little bit in humans, but it’s not as extreme.”

“You hear about, you know, cancer or longevity — I mean, longevity is absolutely impossible to measure in a human study,” Ethan Weiss tells Inverse. Weiss is a researcher and cardiologist affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco who has also studied intermittent fasting.

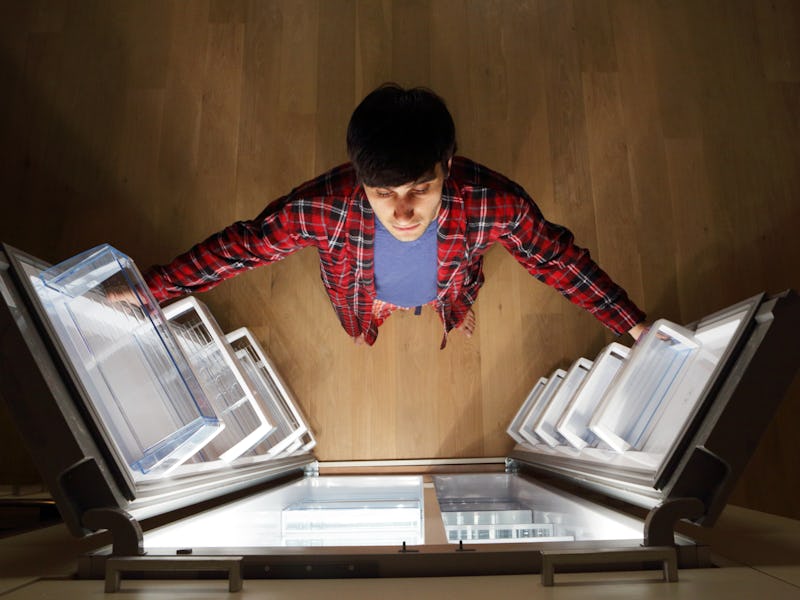

Mice on restrictive fasting schedules can transform their health, but we might not be able to do the same.

What the human studies show — Human studies have shown promising health benefits with certain intermittent fasting regimens. But they’re typically very different from the mouse studies. This is pretty much because humans often can’t stick to eating every other day — the practice that produced such impressive health benefits in mice.

“Nobody’s ever going to do that. And we’ve known this. I mean, I’ve known this, and we all know this,” says Longo.

Some people in online forums often describe personal regimens that are almost as restrictive or even more so — like OMAD (one meal a day), or very long fasting periods —and discuss potential benefits that haven’t been demonstrated in humans, like longevity or cognitive improvement.

“If you do alternate-day fasting, or if you fast every day, and you skip breakfast every day, that’s clearly associated with negatives and it’s a heavy burden — very hard to do,” Longo says.

Instead, he says, people who want to benefit from intermittent fasting should go less extreme — with 12-hour eating windows, for example, or with a “fasting-mimicking diet” on occasion, something he’s testing in a clinical trial on now.

“We’re starting to see lots of benefits, very little side effects,” Longo says. “The compliance has been very high, especially if you say, ‘you need to do it once every four months,’ so you pick the time when you do so.”

There are a handful of clinical trials that have tested alternate-day fasts with people — one which involved Varady, which saw participants put on a fasting schedule that allowed them 125 percent of their normal calorie intake every other day, and 25 percent on their “fast” days. More than a third —38 percent — of the people in the fasting group dropped out. And those that stayed, along with another group that just cut their calories by 25 percent, didn’t see much of an advantage in weight maintenance or loss, or in heart-health markers.

Why it’s hard to study intermittent fasting

Intermittent fasting is not well-researched in humans.

In the world of nutrition research, it’s relatively easy to put animals like mice on a diet that cuts their calories in half and limits when they eat to a few hours of the day. When it comes to humans, however, nutrition studies get complicated.

It’s expensive and time-consuming to keep humans in a controlled environment — a hospital or a hotel, for example — and control every meal they eat. And that’s before you even get to the ethics of limiting people’s access to food.

“That’s the kind of pure science experiment,” Weiss tells Inverse.

Instead, studies on dietary interventions tend to ask people to track what they eat and report back to researchers. Unfortunately, people also tend to underestimate the calories they take in and overestimate the energy they expend. They might misremember or exaggerate what they ate and what they didn’t.

In one of Weiss’ studies, for example, researchers gave participants a dietary recommendation of time-restricted eating (16:8 schedule) to test the effectiveness of the recommendation itself. The idea here is that this would test an effect similar to what people would experience in the real world if they read about the benefits of intermittent fasting online, for example.

“We obviously had no way of measuring whether people were doing what they said they were doing, other than them saying they were doing what they said they were doing,” Weiss says.

The study found that in people who followed the recommendation, time-restricted eating by itself had little to no effect.

Fasting and other diets like “very low energy diets” that cut back drastically on calories, or ketogenic diets, may actually increase the ease of adherence because, counterintuitively, they seem to make people less hungry.

But the results that come from asking a human to restrict their eating to a window of hours of the day are still very different from the ones that can arise from feeding a mouse a designer diet in a lab on a strict schedule.

But it can be hard, as a human, to know the difference.

This article was originally published on