Disparities stem from longstanding, systemic issues and biases.

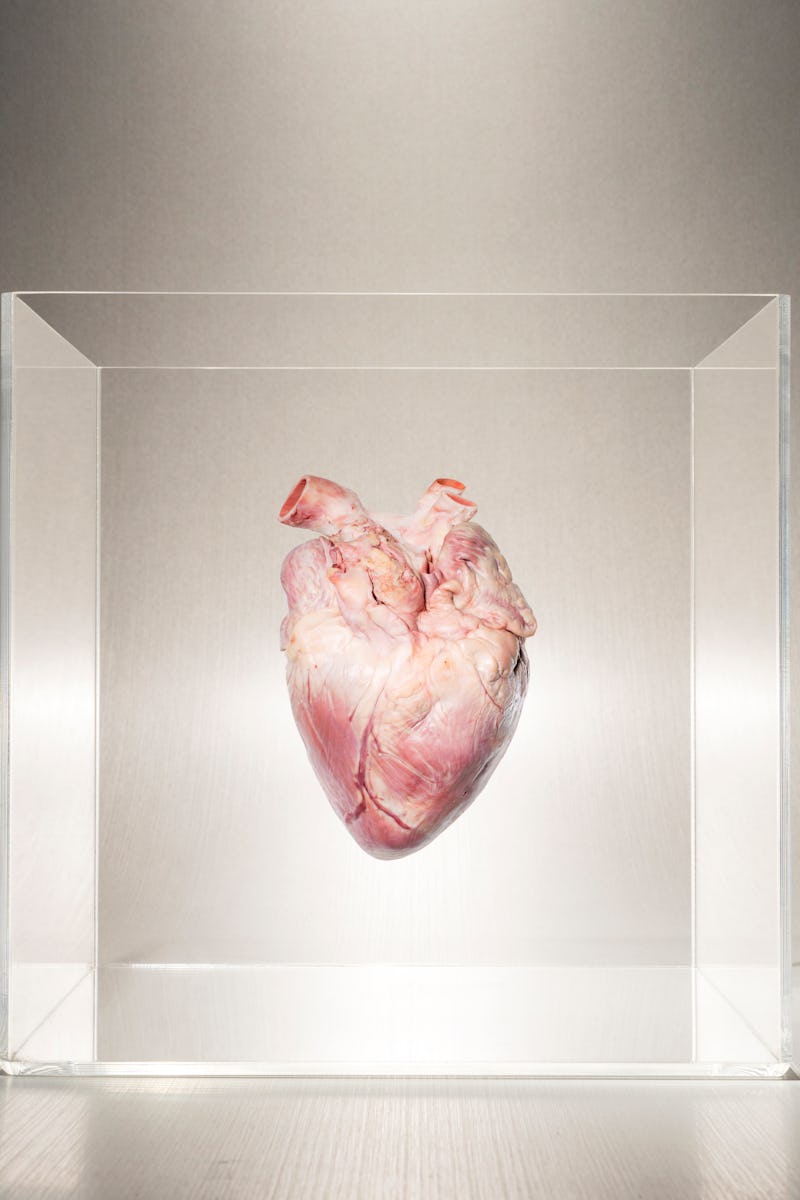

Outcomes of a lifesaving procedure reveal systemic racism

Racism causes significant health care disparities, a new study examining young, Black patients finds.

by Sarah SloatA new study of 22,997 adult heart transplant recipients reveals evidence of significant disparities in health care, driven by systemic racism.

Black young adults are twice as likely to die in the year following a heart transplant compared to non-Black transplant recipients of the same age. Across all age groups, Black heart transplant recipients had a 30 percent higher risk of death following the procedure.

The analysis, published Tuesday in the journal Circulation: Heart Failure, adds to a mountain of evidence of inequity in healthcare and the potentially fatal consequences of racism.

"We could reduce overall racial disparities in heart transplantation."

Black Americans have a higher incidence of cardiovascular diseases and resulting complications — a reality driven by socioeconomic inequity, inadequate access to healthcare, lower-quality care, and the implicit bias of medical providers and insurance companies.

But this study also presents a path forward. Senior author Dr. Eroll Bush, an associate professor of surgery and surgical director of the Advanced Lung Disease and Lung Transplant Program at Johns Hopkins University, tells Inverse the research highlights two critical issues:

- A subpopulation in need of improved support

- The time when this support is most needed

“We found that young, Black heart transplant recipients are disadvantaged in our current system,” Bush says.

“Fortunately, we identified a discrete period, the first year, where young Black heart recipients are at highest risk of death. If clinical research, moving forward, focuses on targeted interventions for young, Black recipients during this period, we could reduce overall racial disparities in heart transplantation.”

What are the risks of a heart transplant?

During a heart transplant, a diseased heart is removed and replaced with a healthy heart from an organ donor. This heart is matched to its recipient by blood type and body size. The need for a heart transplant can be due to a heart attack, high blood pressure, or a viral infection.

A heart transplant can be a life-saving measure, but the procedure is risky. Primary graft dysfunction is the most frequent cause of death the first month after a transplant. The immune system may also reject the new heart. In turn, recipients have to take medication to suppresses the immune system, which can have negative side effects, and need to regularly see their cardiologist to monitor progress.

Survival rates are at about 85 percent at one year post-surgery. Medical expertise and surgical technique in heart-failure management have improved, Bush says, and “resulted in progressive improvements in survival for heart transplants as a whole.”

“By looking at groups as a whole, we have masked our knowledge of subgroups of recipients that do not receive the benefits of those advances equally,” he says.

What’s new — Scientists already knew Black recipients of heart transplants have significantly worse outcomes compared to non-Black recipients, but they did not know exactly what factors may contribute to these outcomes.

Senior author Dr. Errol Bush is an associate professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

The study team evaluated the data of 22,997 adults who received heart transplants between January 2005 to 2017, comparing risks of mortality between Black and non-Black transplant recipients in four age groups: 18 to 30 years, 31 to 40 years, 41 to 60 years, and 61 to 80 years. In total, there were 4,584 Black heart transplant recipients, 33.6 percent of them female, included.

Black recipients had a 30 percent higher risk of death. Age also emerged as an especially salient point of difference: Black heart transplant recipients between the ages of 18 to 30 were associated with 2.3 times higher risk of death, especially during the first year after a transplant.

The cause — These results emerged despite adjusting the data for recipient, donor, and transplant characteristics. Adjustments for socioeconomic status and immunosuppression regimen at discharge could also not account for the observed disparities.

This isn’t to say insurance doesn’t play a role in equity — it just can’t explain, or drive it in full. Organ transplantation is a “complex operation that requires exceptional lifelong, specialized medical, and surgical care,” Bush explains, as well as access to financial and healthcare systems that may “unfairly be more limited in younger patients.” The financial burden, for some, may be insurmountable — limiting the ability to attend follow-up visits and stick to medication regimes.

Higher rates of cardiovascular disease and its complications may also be an “effect of psychosocial factors as a result of a lack of diversity in medical professionals, mistrust of healthcare systems, and perceptions of marginalization within the healthcare community,” Bush says. The team also hypothesizes more severe illness and comorbidities before a transplant may influence mortality rates for recipients between the ages of 18 and 30.

What’s next — Ultimately, more research is needed to precisely pinpoint and understand the factors that contribute to mortality in Black heart transplant recipients — especially in the first year after a transplant. It is increasingly understood that structural racism is a fundamental cause of poor health and disparities. Now, new protocols are necessary, Bush says.

“Clinical decision-making and clinical trials should focus on individualized and unique sets of risk factors that contribute to a higher risk of mortality among young Black recipients, especially in the first year post-transplant, in order to reduce long-standing disparities in heart transplant outcomes,” he says.

“By identifying this health disparity that was found in our study, the heart failure community can now more closely investigate and potentially intervene at earlier time points to reduce racial disparities in heart transplantation.”

Abstract:

Background: Black heart transplant recipients have higher risk of mortality than White recipients. Better understanding of this disparity, including subgroups most affected and timing of the highest risk, is necessary to improve care of Black recipients. We hypothesize that this disparity may be most pronounced among young recipients, as barriers to care like socioeconomic factors may be particularly salient in a younger population and lead to higher early risk of mortality.

Methods: We studied 22 997 adult heart transplant recipients using the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients data from January 2005 to 2017 using Cox regression models adjusted for recipient, donor, and transplant characteristics.

Results: Among recipients aged 18 to 30 years, Black recipients had 2.05-fold (95% CI, 1.67–2.51) higher risk of mortality compared with non-Black recipients (P<0.001, interaction P<0.001); however, the risk was significant only in the first year post-transplant (first year: adjusted hazard ratio, 2.30 [95% CI, 1.60–3.31], P<0.001; after first year: adjusted hazard ratio, 0.84 [95% CI, 0.54–1.29]; P=0.4). This association was attenuated among recipients aged 31 to 40 and 41 to 60 years, in whom Black recipients had 1.53-fold ([95% CI, 1.25–1.89] P<0.001) and 1.20-fold ([95% CI, 1.09–1.33] P<0.001) higher risk of mortality. Among recipients aged 61 to 80 years, no significant association was seen with Black race (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.12 [95% CI, 0.97–1.29]; P=0.1).

Conclusions: Young Black recipients have a high risk of mortality in the first year after heart transplant, which has been masked in decades of research looking at disparities in aggregate. To reduce overall racial disparities, clinical research moving forward should focus on targeted interventions for young Black recipients during this period.

This article was originally published on