“like a sneeze guard at the salad bar."

In the fight against Covid-19, a UCLA lab is cranking out face shields

Using 3D printing and laser cutting, engineers at UCLA are cranking out the face shields as quickly as they can, sharing their products with doctors fighting Covid-19.

by David GrossmanMasks aren’t enough. That’s the realization medical workers across the country are starting to realize in their war against Covid-19, an enemy with no need to sleep or eat.

It spurts out of infected patients like pollen from a flower, instituting dry coughs that send microscopic water droplets into the world. Face shields offer the next level of production to medical workers fighting off infection, and Jacob Schmidt, a bioengineering professor at UCLA, is part of a team electronically fabricating these shields.

Schmidt and his team work out of UCLA’S Innovation Lab, a "makerspace" dedicated to 3D printing and laser cutting. A professor of 17 years, his also the Innovation Lab’s director. On a typical day, the space holds around 50 students and teachers.

As for the Lab's current population, Schmidt tells Inverse, “well, I’m here.”

Schmidt and his fellow engineers realized that shields were needed “basically from seeing the news,” which is filled with horror stories of hospitals running out crucial supplies needed to protect medical workers. While Schmidt may be alone in the Innovation Lab, he finds himself in the unlikely company of hairstylists and fashion designers who have stepped where America’s patchwork and some say broken, medical supply chain has failed.

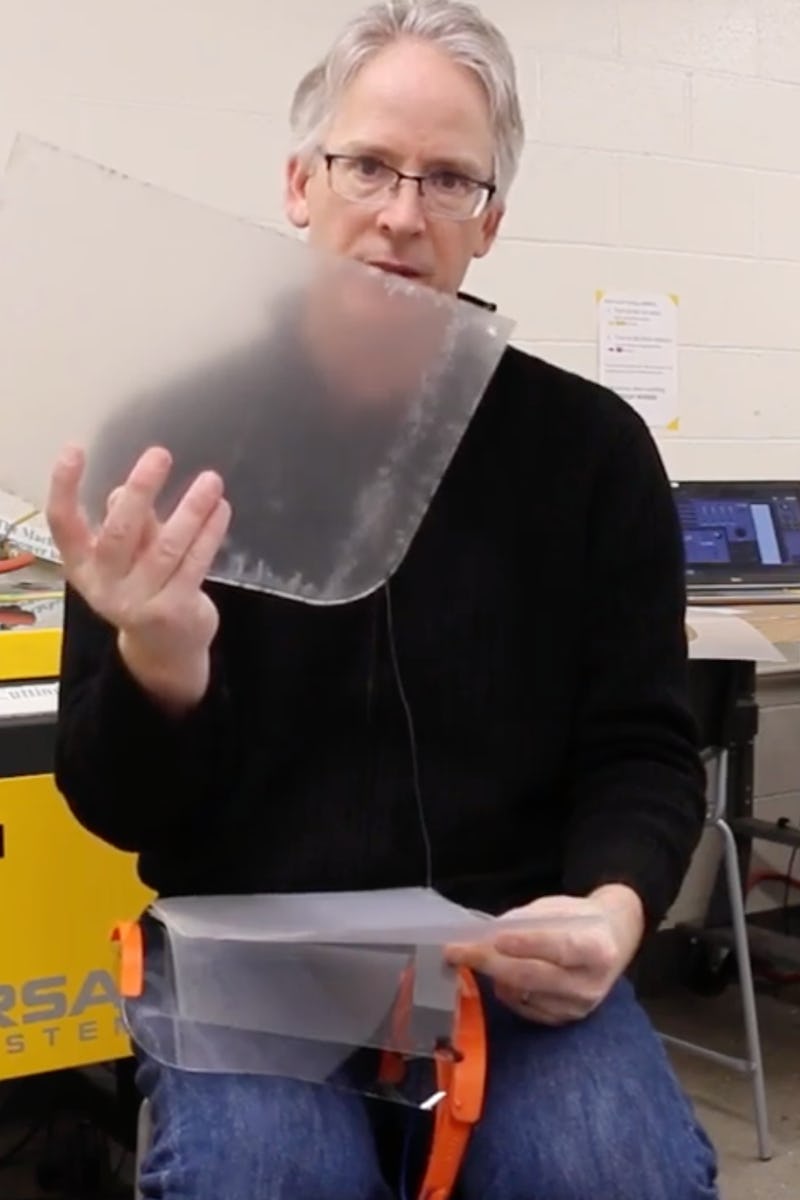

Schmidt is as comfortable with electronic fabrication as Christian Siriano is with a thread and needle. Working with Doug Daniels, director of the Lux Labs at the UCLA Library, the team has created what Schmidt calls a “welder’s mask of clear plastic” that could offer the next level of projection.

They are simple devices, with a strap around the forehead and foam padding in the back for comfort (a necessity when they’re being worn all day).

“Makerspaces are places where you can do prototyping and small-batch production very rapidly and inexpensively,” he has said in a press statement. “These qualities are in high demand right now, as we are being forced to come up with improvised solutions to address the lack of traditional equipment and devices.”

Right now, their work process is similar to others around the world: as far apart as they can get. “I’m here in a room with my 3D printers and laser cutters, and Doug Daniels is in his office and he’s got all his 3D printers there. Sometimes we’ll just leave stuff outside the building.

The shields

A quick reminder: 3D printing is an “additive process” in which a machine adds layer upon layer of material based on a model, eventually creating a recognizable object. Laser cutting gets similar results in the opposite direction: it’s a “subtractive” process, meaning that it uses a laser to cut away from a block of material. Both can make objects fast, but 3D printing works best for making small batches. Laser cutting can make things in bulk.

“With the 3D printing, we were getting maybe 150 out a day. UCLA Health alone wanted 25,000, so that wasn’t going to work. So then we started to look around at different designs — the nice thing about the 3D printed one is that it can be sterilized and reused, but the rate of production is so low.

"There are some designs for laser cut face shields that are just the face shield and an elastic band. That stuff — it’s so simple and the laser cutting is so much faster. That we can make at least a 1,000 day.”

But there were tradeoffs. “The problem with [the laser cut masks] is that the foam, typically, can’t be sterilized once it's contaminated. So it’s single-use.”

A laser cutter making plastic sheets.

Even with that limitation, the face shield is valuable. N95 masks filter out the air a person breathes, which is crucial for catching many of the tiny droplets that scientists believe transmit the novel coronavirus.

“It’s just that if you’re treating a patient and they sneeze on you,” Schmidt tells Inverse, a face shield becomes “like a sneeze guard at the salad bar.”

They’re mainly for medical use—”I wouldn’t wear one one to the grocery store,” Schmidt says, although considering how people are considering hazmat suits to get to the grocery store these days, that might not stop them.

Makers like Schmidt are familiar with the rush and excitement of product design, but there’s never been a product, or a demand, like this.

“A lot of times, what we’re doing is, we have Zoom meetings,” Schmidt explains. “The people that are making stuff — we’re very excited to be making a difference, and at the same time, things are very frantic. At least here in Los Angeles, it hasn’t fully hit the fan yet like it has in New York. We’re trying to do things as fast as we can.

There’s definitely a lot of stress, but I feel like the campus is pulling together. We’ve been contacted by so many people saying ‘I’ve got a 3D printer at home, what can I do?’”

The challenge facing the world right now is too great for the UCLA Innovation Lab to handle alone, Schmidt knows. “

We’re going to need a million face shields, or ten million face shields, or something like that. 3D printing, at least at the scale that we have it, can’t really do it.”

But even in overwhelming odds, his team is doing what people have done since the dawn of civilization: make something, and then make it better.

“The one thing that’s been really helpful, even at our small level, is that we’re making designs for things. We’re printing something, and the same day we’re taking it to a doctor who says ‘When I use, this is what needs to get changed.’ Okay, we’ll go back, we’ll make a new design, we’ll iterate that design.

"That’s something that is really, really beneficial during this time. We’ve gone through three, four, five different design changes in a weekend we’re getting to a point where we’re saying, okay the doctor signed off, this is the design we’re gonna use, and then we go to the injection mold and start making parts at really high quantities".

"Prototyping is really valuable," Schmidt tells Inverse, and he's right no matter what the product. It's just that this is one could be the difference between life and death on the front lines.