Black veterans deserve better than Call of Duty

We just want to live, and we’d love to be taken seriously.

As a Black U.S. military veteran, I don’t see myself represented in a lot of games, unless they start with the words “Call of Duty.”

At 18, I joined the military because I wanted a better life. Growing up in the ghetto, video games were a distraction from a life surrounded by poverty and violence. Gaming kept me off the street. It was literally a life-saver. I’m a Black man, originally from the Chicago neighborhood of Bronzeville, and one of my greatest fears was to end up back in the ‘hood. Four years of the Navy was enough for me to know I was done with it. It was time to move on.

After more than a decade, I got back into video games, but I had no interest in Call of Duty. I was fed up with the patriotism the military tried to brainwash me into believing, and in no mood to relive any part of that experience. I began gaming again when I was nearly 26, only because my then-roommate in Brooklyn was a gamer. I wanted to fit in, and we didn’t connect on any other level, save for both being veterans.

I didn’t expect to fall in love with — and even identify with — Black characters in video games. The two that really stand out are Prototype 2 and Mafia III. The entertainment value and replayability of both games is high. But it took years for me to realize the portrayals of vets — particularly Black vets — in these games are problematic, even irresponsible.

James Heller, the main character of Prototype 2.

Prototype 2 is an open-world action game that’s absolutely glorious by 2012 standards. If you’ve never played it, here’s a short rundown: ex-Army sergeant James Heller goes full Black Rambo in NYC after a devastating virus morphs the city’s population into hellspawn and zombies. He’s intent on getting revenge for his wife and his daughter, who were killed somewhere during this supernatural Afghanistan-like occupation of America.

Heller can fly and sustain more damage than any person in real life could possibly endure. Prototype 2 sees you destroying all kinds of virus-morphed creatures in a way that feels almost therapeutic — especially in late 2021. Heller’s frustrations with the government are a thing I could identify, during a time I felt alone, bitter, forgotten. If I could talk to no one else, at least I could find comfort with this video game character.

“You don’t uplift the community you set out to make better — it’s merely regime change.”

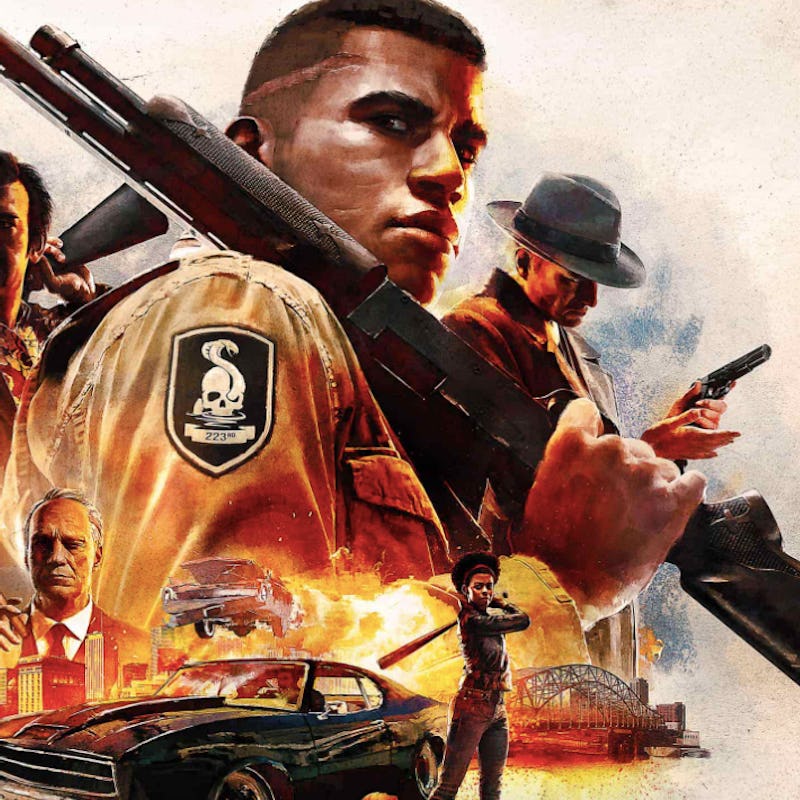

Mafia III takes place in a world where the ‘60s are still alive and the N-word gets around like herpes. It makes total sense that the player-character is mad, but protagonist Lincoln Clay cannot, and should not, get away with what he gets away with. Clay literally guts the game’s version of 1960s New Orleans (in-game referred to as New Bordeaux) like Edward Scissorhands chopping up 1990s Chicago.

In Mafia III, you bust up drug rackets and then take over the drug trade. You replace a flawed system with another flawed system. You don’t uplift the community you set out to make better — it’s merely regime change. There were positives, though. I appreciated how one of Lincoln Clay’s major motivations was to clean up neighborhoods. He exposed racism, was an advocate for the underserved, and dismantled some of the systems that have kept Blacks out of positions of power, prestige, and prosperity for generations. I was impressed by the game’s critiques of systemic racism and gentrification.

The main character of Mafia III, Lincoln Clay.

These games are fun fantasies that momentarily empower the player, but they also support assumptions and stereotypes that are deeply harmful. Killing Klansmen in Mafia III feels gratifying, but it’s still problematic due to the message packed along with it. The symbolism of a Black Vietnam vet going ballistic in a game where you can kill innocent pedestrians as well as disgusting racists lends a lot of credence to the idea that we’re all like that. Not only is there the ever-present stereotype that former service members are constantly violent, constantly crazy, or constantly drunk, there’s the prevailing belief that all Blacks are vicious, dangerous, and blood-thirsty.

I’ve wanted to take it out on The Man on many occasions. I still live under a government where I can get pelted with trash by racists while going down the street and spat on for walking next to a white woman. I will say that these games are satisfying in a way that scratches my itch to see the government burn. The racism embedded within Mafia III helps me realize how much art imitates life; even a complete overhaul of our society will only chip away at a fraction of people’s hateful views toward each other.

James Baldwin once said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost, almost all of the time — and in one's work.”

James Baldwin

Trust me, I get it. I’ve lived in seven states. From the West, to the Midwest, to the East, to the South. I’ve experienced every type of person you can and cannot imagine. From the backwoods banjo to the bourgeois banquet…I’ve been there. I’ve always done it as a Black man. I’ve always had to think of my skin before I thought of myself because people who don’t look like me think that way. This is how it is.

Games like Prototype 2 and Mafia III perpetuate the superhumanization of African Americans. That’s the idea that we don’t hurt in the same way that whites do, and therefore it’s okay that we’re victims of police brutality. That it’s fine to under-prescribe pain meds because we’re just trying to get high, totally side-stepping the possibility we’re actually suffering from a flare-up of a debilitating medical condition. We’re already “supernaturally” good at sports, so maybe we’re also good at tolerating falls from great heights… maybe we can even fly.

“Imagine a game that dives into the tragic status of the American Black veteran.”

Titles like Celeste prove it’s possible for games to tackle depression in a healthy way. The Cat Lady, though harrowing, provides a positive message about suicidal ideation. So when do vets get a game like that — especially vets like myself, and in my skin?

Veterans, and especially Black veterans, deserve a game that provides a realistic portrayal of them and their experiences. And sure, if the game was about standing in line at the VA for four hours just to get turned down for benefits, you’d be begging to unwrap a deck of cards just so you could play 52 pick-up. But imagine a game that dives into the tragic status of the American Black veteran, and explores the problems inherent within the military and the government as a whole in an exciting and empathetic way.

I’d love to see a realistic version of what a Black veteran goes through in a game.

For many veterans, revisiting trauma through video games can have significant mental and emotional benefits. According to the VA, about 11-20 percent of vets from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom suffer from PTSD. Around 12 percent of Gulf War vets and some 30 percent of Vietnam vets have also experienced PTSD at some point during their lifetimes. In a safe environment, gaming can help vets think about traumatic events they’ve suffered through during a time of peace, in order to help them realize those memories cannot hurt them.

I’d love to see a realistic version of what a Black veteran goes through in a game. It can include the racism. But there is no shooting. There is no journey into, or glorification of, this idea that veterans with mental health issues are just another part of the problem. There is no widespread epidemic of strung-out Black vets out for your funds and your sympathy. We just want to live, and we’d love to be taken seriously.

Make that video game. I dare you.

This article was originally published on