A Forgotten Horror Movie Was The First To Introduce The Cinematic Werewolf

Before The Wolf Man, there was Werewolf of London.

Although it was technically not the first werewolf movie (that honor goes to the long-lost and now forgotten 1913 short, The Werewolf), Werewolf of London was the first feature-length motion picture in cinema history to deal with the subject of lycanthropy (or “lycanthrophobia,” as it’s called in the film itself). Produced by Universal Pictures, the film starred Henry Hull as Dr. Wilfred Glendon, a world-famous British botanist (apparently botanists could be celebrities back in the day) who ventures into Tibet to find a rare flower, Mariphasa lumina lupina, that allegedly can blossom in moonlight. He does find the flower, but brings home something much worse.

While procuring three sample buds, Glendon is attacked and bitten by an animalistic humanoid creature. He makes it home and creates an artificial source of moonlight in his lab in order to make Mariphasa bloom, after which he’s approached by Dr. Yogami (Warren Oland, creepy), a fellow botanist who claims they met in Tibet. Indeed they did: Yogami was the creature that attacked Glendon, and claims that Glendon will turn into a werewolf himself thanks to Yogami’s bite — unless the plant, which can keep lycanthrophobia in check, blooms successfully.

The first thing to know about the movie, which was directed by Stuart Walker from a screenplay by John Colton (from an original story by Robert Harris), is that the title is misleading: there are actually two werewolves in the film, Yogami and Glendon. With only three buds of Mariphasa available, Yogami coldly goes about stealing them from Glendon’s lab, all while warning Glendon that he will turn into a werewolf and instinctively seek to murder “the thing he loves best” — in this case, Glendon’s wife Lisa (Valerie Hobson), whom Glendon has been neglecting but finally does everything he can to protect once his transformations begin.

Werewolf of London was originally conceived as a vehicle for horror icons Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, with the former tagged to play Glendon and the latter cast as Yogami. That would have been a blockbuster combination, but Karloff was already committed to filming Bride of Frankenstein and the studio was hesitant to muck around with that movie’s schedule (Valerie Hobson appeared in both films, incidentally, playing Dr. Frankenstein’s wife in Bride). Hull was cast after a star turn in Great Expectations the year before, with director Walker coming along as well. But Hull’s involvement turned out to be problematic from the start.

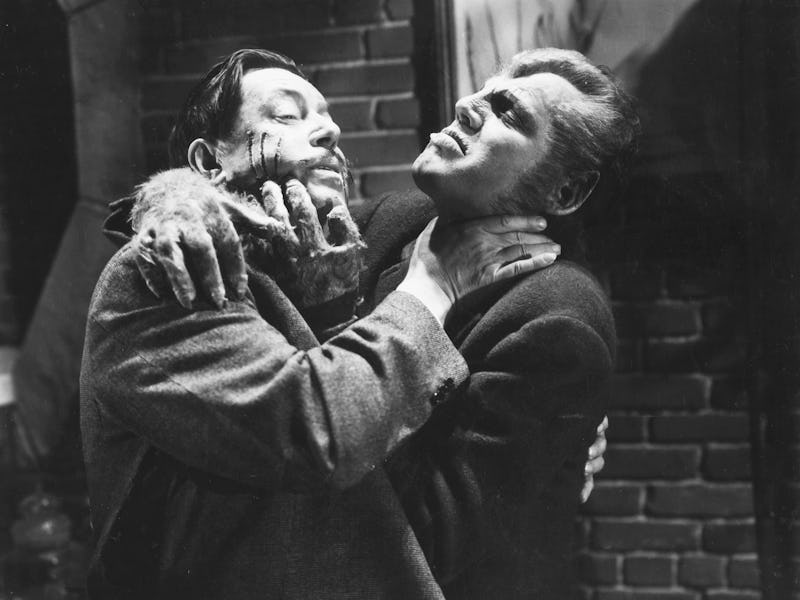

For one thing, the actor refused to don the elaborate makeup devised by the legendary Jack Pierce (who had previously turned Karloff into Frankenstein’s monster and the Mummy), forcing Pierce to come up with something less extensive. The final design, while distinctive in its own way, resembled a bat or rodent more than a wolf. The transformations are handled effectively onscreen (for the time), but Glendon’s forays into the night to slaughter innocent citizens are quite bizarre, with the monster stopping to don his hat, scarf, and coat on his way out the door.

Inspired by Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Werewolf of London sought to position its monster as a scientist with dueling personalities.

Although the werewolf action overall is pretty good, there are bigger issues with both Hull’s performance, the script, and Walker’s direction. Arguably influenced by Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde three years earlier, the movie paints Glendon as a scientist so driven by his work that he is virulently antisocial to others in his social circle and almost cruelly dismissive to his wife (until she starts blatantly palling around with an old childhood flame, a surprisingly bold twist for 1935 which finally snaps Glendon out of his self-absorption). Distant and cold throughout the film, Hull’s Glendon is hard to sympathize with even during the movie’s tragic finale.

On the plus side, the shadowy, noirish cinematography by Charles Stumar is quite good, especially during the scenes of the werewolf on the prowl, and both Oland and Hobson are relatively strong in their roles. Less effective are two old ladies, Mrs. Whack (Ethel Griffies) and Mrs. Moncaster (Zeffie Tilbury), the latter of whom rents Glendon a room in her boarding house when he’s trying to lay low. Eating up a lot of the 75-minute runtime, the two women drink excessively and smack each other around in what’s supposed to pass for comic relief.

Werewolf of London did not fare well at the box office, but Universal attempted to mine the same territory just six years later with Lon Chaney Jr. in the now-classic The Wolf Man. That film developed a more extensive folklore around the werewolf and set the tone for scores of movies to follow, especially in portraying the cursed title character in a far more empathetic light.

Nevertheless, Werewolf of London did leave a modest cultural paw print: the makeup inspired that of films like Mike Nichols’ Wolf (1994), which also incorporated the monster into a cosmopolitan, upper class milieu. An American Werewolf in London cribbed the name and setting, if nothing else, while Warren Zevon’s rock radio staple “Werewolves of London” played off the image of a well-dressed lycanthrope lurking around the streets of London town. There was even a 1987 video game adapted from the film. Nine decades later, the title beast is still one of horror’s classic monsters — it seems this botanist did become world-famous, after all.