With The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling Changed Television For All Time

You are about to enter the past.

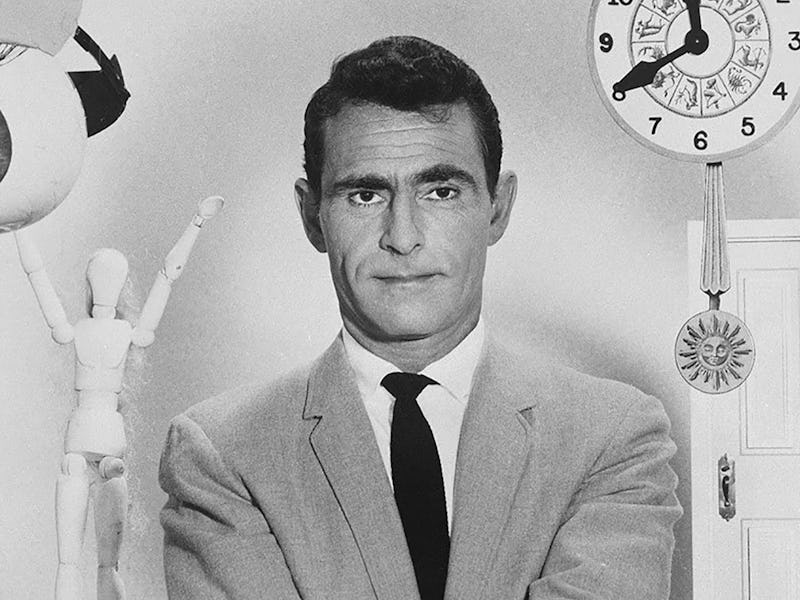

Sixty-five years ago, on October 2, 1959, network television underwent a seismic change, even if no one knew it at the time. Why? The Twilight Zone premiered on CBS. Created and hosted by Rod Serling, who also wrote 92 of an eventual 156 episodes, the series was a weekly half-hour anthology of science fiction, horror, and fantasy tales, many of which were allegorical and ended with both a twist and a moral.

Serling, who’d become one of TV’s most acclaimed writers for his socially conscious dramas like Patterns and the Emmy-winning Requiem for a Heavyweight, thought he could get around network censors and leery sponsors by couching controversial topics in fantastical stories. “A Martian,” he once said, “can say things that a Republican or Democrat can’t.”

Although it came of age in the 1940s and ‘50s as literature, science fiction still wasn’t taken seriously on screen. While the ‘50s had yielded some breakthrough films like The Day the Earth Stood Still, Forbidden Planet, and The Incredible Shrinking Man, much of Hollywood’s output still consisted of cheap drive-in quickies about flying saucers or giant bugs. TV was worse: most of what aired was juvenile fare like Captain Video and Tom Corbett, Space Cadet, while early, ambitious anthologies like Tales of Tomorrow and Science Fiction Theatre were marred by primitive production values.

While low budgets still hampered The Twilight Zone, generally better production values and literate writing by Serling, along with the likes of genre greats like Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, and Ray Bradbury, enhanced the moral gravity of the stories. That, along with its many shocking endings, gave the show added dramatic weight. And sure enough, Serling didn’t skimp on addressing themes that might not have passed muster with censors if they hadn’t been dressed up in genre trappings.

In “The Obsolete Man,” a librarian is sentenced to execution in a futuristic totalitarian society where books are banned — still a problem today — while “The Shelter” and “The Monsters are Due on Maple Street” expose the façade of friendliness and humanity that exist in “typical” American communities. In the former, people form a violent mob as they fight to cram into the only available bomb shelter during a nuclear scare, while in the latter, a conspiracy theory that alien invaders have infiltrated bucolic Maple Street leads to a barbaric, bigoted response.

Prejudice reared its ugly head in “The Eye of the Beholder,” where a woman who appears beautiful by conventional standards is declared a defective outcast by her people, who are portrayed as humanoids with pig-like faces. Another episode showed a former SS officer tormented by the ghosts of everyone he murdered when he returns to a now-abandoned Dachau.

The Twilight Zone’s debut episode, “Where is Everybody?”, sees a man try to puzzle out why both a town and his memories are empty.

It’s a genuinely shattering episode, and at the end of it, when a character asks why the concentration camp must remain standing, Serling responds with one of his most chilling closing narrations. “They must remain standing because they are a monument to a moment in time when some men decided to turn the Earth into a graveyard,” he says. “Into it, they shoveled all of their reason, their logic, their knowledge, but worst of all, their conscience. And the moment we forget this, the moment we cease to be haunted by its remembrance, then we become the gravediggers.”

It was episodes like these — along with sci-fi outings like “The Midnight Sun” and “To Serve Man,” frightening horror stories such as “The After Hours” and “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” and cautionary tales about technology and corporate greed like “The Brain Center at Whipple’s” — that captured the imagination of audiences, as well as those of future creators ranging from Stephen King to M. Night Shyamalan to Jordan Peele, who executive-produced and hosted a short-lived third reboot of the series in 2019 and ‘20 (previous remakes aired in the late ‘80s and early 2000s, while a feature film was released in 1983).

The impact of Serling’s socially conscious program can be felt in Peele’s films, his twist endings almost certainly influenced Shyamalan’s work, and more recent anthology shows like Black Mirror have aimed for the same combination of speculative fiction and societal commentary that Serling perfected decades earlier. The idea that sci-fi, horror, and fantasy could be taken seriously as complex stories with resonance and urgency, meanwhile, is evident in nearly every genre show that airs today. That, in the end, is the most important lesson learned… in The Twilight Zone.