The World Wasn’t Ready for Hayao Miyazaki’s Most Surreal Epic

How do you live?

When The Boy and the Heron premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival last year, the air was humming with excitement for Hayao Miyazaki’s newest film. The mysterious cosmic epic, a whopping seven years in the making, had long been advertised as the anime titan’s last movie, before he announced he was once again delaying his retirement. Still, it had been a decade since his last final film had been met with a muted response, so people were ready to be wowed again by the director of masterpieces like Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle. But that hum of excitement was soon replaced by confused murmurs, as audience members trickled out of the screening of Miyazaki’s most bewildering movie yet.

The Boy and the Heron has been described as Miyazaki’s “most personal” film, taking inspiration from his wartime childhood and a novel he loved in his youth, How Do You Live. But to summarize it is difficult: in broad strokes, it’s about a 12-year-old boy named Mahito who, after suffering the loss of his mother in the firebombing of Tokyo, embarks on a surreal adventure through a waterlogged alternate world to rescue his pregnant stepmother, who also happens to be his aunt. There, Mahito encounters man-eating birds, seafaring women, and magical creatures, and strikes up a wary alliance with a talking heron who promises him a chance to see his mom again. It’s a strange adventure story, one that becomes more mystifying as it’s revealed that Mahito’s great-uncle created this alternate world after he encountered a powerful object from space, and who wants Mahito to take charge of it before the world crumbles into dust.

It’s easy to see the “semi-autobiographical” parts of The Boy and the Heron in the real-world scenes, where Mahito grows up in a wartorn Japan and struggles with his factory-owner father profiting from the conflict (Miyazaki had similar feelings regarding his own father’s management of a munitions factory). But it’s the idea that the alternate world actually resonates more with Miyazaki’s own life that puts off casual moviegoers.

At the end of The Boy and the Heron, Mahito is faced with a choice: return to a dangerous reality, or stay in the alternate dimension and create a better world for himself. Ultimately, he chooses to go back to the real world, as terrible as it may be, because the imagined world is already on the verge of decay. This choice feels like Miyazaki speaking to and about himself: he’s built beautiful imagined worlds, but nothing can beat reality.

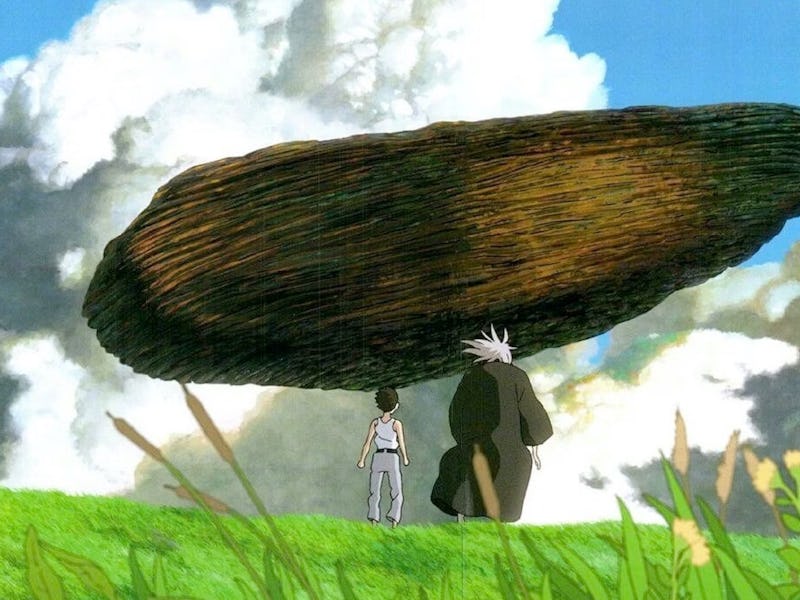

Mahito and the Heron form a troubled alliance.

Maybe he’s the old man, doomed to end with the fake worlds he made, as he encourages his grandson to live in the real world. Maybe he’s the young boy, ready to leave his imagined worlds behind and finally embrace reality. Or maybe the great-uncle is actually his longtime collaborator and fellow Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata, and The Boy and the Heron is his way of saying goodbye to him after his 2018 passing.

It’s a big bundle of metaphors that, even a year later, Miyazaki’s biggest fans are still unpacking. But it’s what makes The Boy and the Heron such a rich movie to revisit, even if it’s not the cozy, whimsical Ghibli adventure moviegoers might have expected. Its arrival to its new streaming home, Max, was even accompanied by a fascinating documentary on the seven-year making of The Boy and the Heron, and if a deep dive into Miyazaki’s psyche and childhood trauma isn’t what you’re up for, Robert Pattinson deranged voice performance as the Heron still makes it worth your while.