You need to watch the best steampunk sci-fi classic on Amazon Prime ASAP

This bizarre 1995 fantasy runs on a nightmare logic all its own.

What is steampunk? In this most giddily antiquarian of science-fiction subgenres, the past is no longer the past, but the future hasn’t exactly left it behind. Instead, steampunk blends the vanished worlds of yesterday with unrealized worlds of tomorrow. Calling upon direct anachronism and unfettered visual creativity to colonize our memories with the forward-thinking substance of dreams, it imagines strange days of future past.

Often, “steampunk” draws inspiration from the Victorian era, with all its steam-powered industrial machinery. A peculiar strand of retrofuturism, steampunk doesn’t mourn vintage futures that never came to pass. Instead, it actively tinkers with outmoded technologies to turn lost ages into playgrounds for science fantasy.

Few films, in this vein, capture the spirit of steampunk with as much peculiar daring and imagination as The City of Lost Children, Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro’s expressionist 1995 fairy tale about a mad scientist kidnapping children in an effort to share their ability to dream. Now that it’s streaming on Prime Video, here’s why you should revisit this dazzling cult classic.

How’s this for an opening sequence? Our first image is of a snowman through a window, its blackened eyes staring forward in a garish approximation of vision. The camera moves back to reveal a windowsill of spring-loaded toys, including a similarly wrong-looking toy soldier crashing its cymbals together. We’re in a little boy’s bedroom. It’s Christmas Eve.

As the wide-eyed Denree (Joseph Lucien) looks on from his crib, Santa Claus descends into the fireplace, lowered by a rope, and dusts himself off, winding up a tin circus elephant and presenting it to the boy. But much to Denree’s surprise, another Santa follows, then another. As the room fills with Santas, each creepier than the last, his initial fascination turns to terror.

The boy reaches for a teddy bear, the only comforting object in view, as more Santas appear at the window, and some enter through his bedroom door. They’re everywhere. The picture becomes warped, rippling as one particularly gaunt Santa approaches. This is the wretched Krank (Daniel Emilfork), though we don’t yet know this and share in the child’s panic — not that learning about Krank when we do, is a source of comfort.

Daniel Emilfork as Krank, in Santa regalia, in The City of Lost Children.

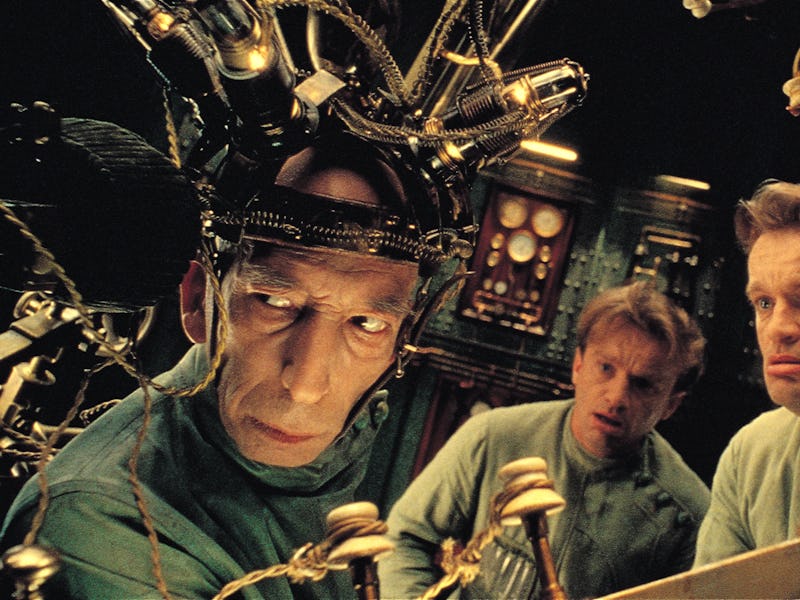

Abruptly, we cut to Krank screaming, strapped into some analog contraption in a sepulchral laboratory. Around him, narcoleptic clones (played by Jeunet regular Dominique Pinon) pick up his cries in a chorus that seems authentic in its bug-eyed befuddlement.

Soon, it’s revealed that Krank has indeed kidnapped Denree, who’s held in a carapace-like structure nearby. Like all the infernal devices in The City of Lost Children, the crudely mechanized contrivances in Krank’s lab feel both clumsily homemade and realized with a furiously off-kilter logic. They are glorious messes of rusted brass, wire, and tubing. Across the lab sits Irvin, a giant brain in a fish tank (voiced by Jean-Louis Trintignant), who intones:

“Who has stolen the child's dream? The mad genius Krank in his evil scheme. To what vicious depths will he not descend? Will the tale turn to tragedy... or have a happy end?”

As storytellers go, that disembodied brain is objectively peculiar and thus a tonally perfect choice to prelude The City of Lost Children. The febrile creation of some vanished scientist, Krank cannot dream and is aging prematurely. To stave off his encroaching demise, this strange man has developed a device that allows him to enter children’s dreams. Unfortunately, these always curdle into nightmares once the children become aware of his surreal intrusions, and Krank shares in their terror.

Ron Perlman in The City of Lost Children.

A subject of revulsion, to himself most of all, Krank is too pathetic to fear, but the grotesque nature of the mad scientist’s torment is exemplified by his Felliniesque compatriots, including Irvin, the clones, his deadly dwarf wife (Mireille Mossé), and a “Cyclops Gang” whose techno-monocles can see sound. Krank’s inverted hideout is revealed to be an abandoned oil rig near an ersatz port city populated by all manner of carnies. Members of the Cyclops Gang travel here to abduct children for Krank’s experiments.

Denree, it turns out, is the adopted brother of a circus strongman living on the mainland, named One (Ron Perlman), who teams up with a scrappy orphan named Miette (Judith Vittet) to rescue him. Along the way, they encounter a pair of conjoined twins called The Octopus (Genevieve Brunet and Odile Mallet), a circus performer (Jean-Claude Dreyfus) who commands an army of fleas, and a mysterious diver who lives under the harbor (to reveal who plays him would be a spoiler).

Ron Perlman and Judith Vittet in The City of Lost Children.

Though jovial in the screw-loose spirit of Terry Gilliam, the filmmaker to whom Jeunet and Caro owe the most, all of the adult characters also display a noirish cynicism. They haunt the shadows of the film like ghosts, in thrall to the pervasively hallucinogenic atmosphere. Jeunet and Caro execute some bravura sequences around these characters — such as one in which a single teardrop falls through space and sets off a Rube Goldbergian chain reaction — but none of them ever entirely escape the hazy half-reality they inhabit.

The distance at which The City of Lost Children holds us is intentional, allowing our eyes to wander the frames, which teem with bizarre objects and sight gags, rather than investing squarely in the actors' performances. Adding to the picture’s aesthetic vibrancy is a profoundly unsettling score (by Angelo Badalamenti, of Twin Peaks fame), capturing the sense of violation inherent in Krank’s evil scheme.

As a twisted kind of fairy tale, The City of Lost Children is about the end of childhood innocence in many ways. But it’s also a film about the lecherous, parasitic sides of our unconscious longing to recapture that innocence, embodied by a child-snatcher so abjectly piteous — and so ashamed of this fact — that he feels like the punchline of some dark, existential joke.

The Octopus.

Throughout, the film retains the feel of a fever dream, its color palette — visualized confidently by cinematographer Darius Khondji — continually unmooring the picture from reality. That port city materializes out of an aquatic-green mist but only partly, retaining a polluted semi-opacity. The film’s murkier browns speak to the drab disenchantment of the adults, whereas the children retain a sense of wonder, visualized in hues of bright green and red. Overall, the dour atmosphere of its overarching world is more dank and mottled.

The City of Lost Children was not Jeunet and Caro’s first collaboration — that would be 1993’s Delicatessen, an equally batty post-apocalyptic vision — but it would prove their last as co-directors. The film was such a success that Jeunet and Caro were shortly thereafter invited to direct their first big-budget Hollywood production: Alien Resurrection, the franchise’s fourth entry. Such a high-profile assignment enticed Jeunet more than Caro, though the latter still assisted with costumes and set design.

As such, it’s easy to see The City of Lost Children as the end of an era, but it also served to propel those behind its uncanny, nocturnal vision into Hollywood; special effects supervisor Pitof and cinematographer Khondji both joined Jeunet for Alien Resurrection. And for steampunk aficionados, the film has since emerged as a cult classic of near-mythic grandeur and bizarro integrity.

The City of Lost Children is now streaming on Amazon Prime.