The Oral History of Repo Man

Four decades after its debut, Inverse tracks down the ragtag crew behind one of the greatest indie films ever made. “If it was a Hollywood movie that had been made about punks and stuff, it would’ve died.”

Somewhere in the California desert, a police officer pulls over a 1964 Chevrolet Malibu as it lurches wildly across the highway. After interrogating the driver, he opens the trunk and is instantly vaporized by a blinding light that reduces him to a skeleton, leaving behind only a pair of smoldering leather boots.

Thus begins Repo Man, a sci-fi cult classic with a nihilistic worldview and a punk rock soundtrack that by all accounts probably shouldn’t exist. Thanks to a mix of very good luck and sheer force of will, what started as a student film from writer-director Alex Cox eventually became one of the greatest independent movies of all time.

“If it was a Hollywood movie that had been made about punks and stuff, it would’ve died,” Cox tells Inverse. “But because it was authentic in its origins and sincere in its intentions, it had more of a life.”

Released on March 2, 1984, Repo Man stars a young Emilio Estevez as Otto, a punk rocker from Los Angeles who loses his supermarket job and winds up repossessing cars after he’s taken under the wing of a repo man named Bud (played by Harry Dean Stanton). Otto is soon wrapped up in a struggle for the Malibu and the otherworldly object in its trunk, leading to a climactic showdown in which the car glows green and flies up into space (with Otto in it).

The plot is propulsive, but it’s the eclectic cast, ranging from real-life punk musicians to Jimmy Buffett as a CIA agent (“He just came to the set,” Cox says. “So we put him in a suit.”) and dreamlike dialogue that make Repo Man stand out four decades later.

To celebrate the movie’s 40th anniversary, Inverse spoke to Cox and seven other members of the cast and crew to tell the definitive history of Repo Man.

The beginning

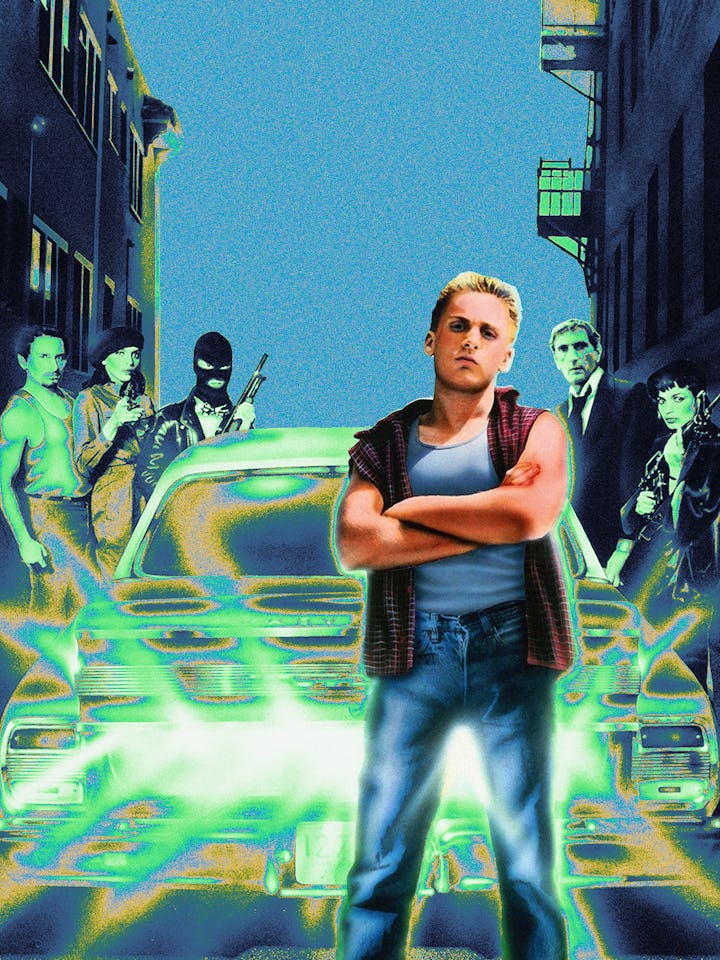

Emilio Esteves in Repo Man.

Still in film school, three students at the University of California, Los Angeles, team up with plans to make a feature.

Del Zamora (plays Lagarto Rodriguez): Repo Man started out as a student film.

Peter McCarthy (producer): We all went to film school at UCLA. Alex was a Fulbright Scholar. Jonathan had been a big sociology professor. I was just a Midwest kid who decided to go out to L.A.

Jonathan Wacks (producer): We were trying to make movies and short films and do edit work and whatever we could get to survive.

Peter McCarthy: There was an old funeral home that had gone bankrupt. I rented out the embalming room and turned it into an editing suite. Jonathan had a nicer office with stained glass windows. We started looking at each other's films. Then we got kicked out. So I found an office for 200 bucks in Venice Beach. The neighborhood was rough.

“I lived in that office on a mattress in the back.”

Jonathan Wacks: One day Alex came by. I was standing outside on Sunset Avenue, and he said, “Well, why don’t we make a feature?”

Alex Cox (writer and director): They said, “We have no dramatic feature scripts right now.” I said, “Well, I will bring you some.” Repo Man was the second script I brought to them.

Peter McCarthy: I hear a motorcycle outside, and Alex comes walking in. He couldn't believe we had an office.

Alex Cox: I lived in that office on a mattress in the back.

Alex Cox (right) and Abbe Wool in Repo Man.

Abbe Wool (video coordinator): It was such a hangout.

Peter McCarthy: I’d cut it into three sections, got some wood and found some glass in the alley. It was really funky, but it was an office. It had a little kitchen and a room off the kitchen that I turned into my bedroom. That was the genesis of Edge City Productions.

Jonathan Wacks: We had a meeting and decided we would write a screenplay for a feature, and whoever’s was chosen would get to direct. Alex came back in a couple of weeks with a script called The Hot Club.

Peter McCarthy: The Hot Club had an apocalyptic feel to it. It was going to be way too expensive.

Jonathan Wacks: We convinced Alex that nobody would make this movie. But that was really an alibi to buy us time to keep working on our scripts. But Alex, who writes at the speed of knots, came back with another script, which was Repo Man.

“Originally, I wanted to do it with Dennis Hopper and Dick Rude.”

Repo Man was the amalgamation of several ideas, mixing together plot elements from Cox’s script for The Hot Club along with dialogue borrowed from real-life repo man Mark Lewis and a story about punk kids originally written by an acting student named Dick Rude.

Peter McCarthy: Dick Rude was very influential for Alex. Dick was his filter into a lot of stuff about American culture, and especially punk culture.

Dick Rude (plays Duke): I was a teenager going to the Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute in Los Angeles. I wrote a script called Leather Rubberneck with a friend of mine from school, about two kids who get drafted. Alex wanted to make the film, but it didn't pan out. So he incorporated it into Repo Man. A lot of the characters, some of the dialogue, some of the ideas, there was quite a bit of it that was used in Repo Man.

Dick Rude in Repo Man.

Peter McCarthy: There was this repo man who lived next door to him. And Alex started going around with him doing repos and came up with this screenplay.

Alex Cox: Mark Lewis, he was our neighbor. I started riding around with Mark on these late night ventures to repossess people’s cars because it seemed like a good idea for a screenplay. And indeed it was. A lot of what is in the script is based on things that Mark and his colleagues told me.

Peter McCarthy: Edge City now owned the screenplay. We bought it from Alex for a dollar.

“All of a sudden, there were lines of actors coming to our dingy little office in Venice.”

Jonathan Wacks: We went through the Yellow Pages and looked up studios and producers and we sat and typed letters. We knew they wouldn’t pick up our phone. We sent hundreds of letters out and got zero responses. So we decided to raise $500,000 and shoot it at UCLA so we could use the equipment for free.

Peter McCarthy: The thing with UCLA is you never wanted to get your diploma. Once you did, you couldn’t go back and use anything.

Dick Rude: Alex and I started casting people for the film, just reaching out and bringing people in.

Jonathan Wacks: All of a sudden, there were lines of actors coming to our dingy little office in Venice.

A hand-made flyer announcing movie auditions for Repo Man.

Del Zamora: I was a struggling actor living in my van. So I came in to audition with my then-girlfriend, and immediately Alex freaked her out. He had a shaved head on one side and then really long shoulder-length hair kind of hiding one eye.

Olivia Barash (plays Leila): My agents didn't know about the movie, and they told me not to go because they didn’t know who these people were, and they thought it was dangerous. I went anyway, and I read in a garage.

From student film to studio movie

“Nesmith sent the script to Universal, and they rejected it.”

As Edge City prepares to start filming on a film school budget, the movie gets a major upgrade thanks to rock-star-turned-movie-producer Michael Nesmith.

Alex Cox: Abbe Wool, who was a very dear friend of mine, and the video coordinator on the film, knew a producer who was a friend of her father, a guy called Harry Gittes, and this Harry Gittes knew Michael Nesmith.

Abbe Wool: Harry asked me what’s up in film school, and I said, “Two of my friends just wrote these great scripts.” He goes, “Well, let me see.” And those scripts were both made into movies in long and circuitous ways.

Jonathan Wacks: Harry Gittes is the guy who J.J. Gittes is named after in Chinatown.

Peter McCarthy: He had done a film with Michael Nesmith called Timerider, and they were looking for more projects. Nesmith had made a lot of money as a Monkee that he had blown living large. One day, he looked out his window in Beverly Hills, and his Bentley was being repossessed. So the Repo Man thing really resonated with him.

Alex Cox: Nesmith sent the script to Universal, and they rejected it. And he went out for a drink with a guy who wanted to be his manager. And this manager looks over at the bar, and there’s Bob Rehme, the head of Universal. And the guy goes, “Hey, Bob, Michael here has got a great script, and you guys turned it down.” The next day, Nesmith got a disgruntled call from an executive at Universal saying, “Oh, I guess we’re doing Repo Man.”

Casting the movie

“Emilio’s agent didn’t want to show it to him.”

Under pressure from Universal, the team behind Repo Man begrudgingly agrees to cast some Hollywood stars.

Peter McCarthy: When Nesmith got Universal involved, the studio was like, “Who are any of these people?” So we had to start looking for alternatives.

Alex Cox: Originally, I wanted to do it with Dennis Hopper and Dick Rude.

Dick Rude: I was going to play Otto, but eventually that fell to the wayside because they needed someone a little more cached and experienced. I was a bit heartbroken, but I was also really stoked to just be making my film and my art.

Peter McCarthy: Emilio’s agent didn’t want to show it to him. But there was a woman named Mari Kornhauser who worked for Martin Sheen and the Sheen family in some capacity. She was a babysitter or something, but she was also a connection through UCLA.

Jonathan Wacks: So she set up a meeting for us at some sushi restaurant. He was a fun guy, and we said, “You want to do it?” He said, “Yeah, sure.”

Olivia Barash: He was a really great actor for our age range. So it was really easy. He was really natural, and it was great working with him.

Abbe Wool: Everyone was kind of suspicious about Emilio, like nepo baby, which we didn't have a term for yet.

Alex Cox: The nepotism of Hollywood was really taking off at that time. A lot of actors got their sons into the profession.

Casting the role of Bud proved slightly more difficult, and included a 14-hour drive from Los Angeles to Taos, New Mexico.

Peter McCarthy: We had thought of Dennis Hopper, but nobody could get anything to him. We thought, “Why don’t we drive to Taos and see if we can run into Dennis Hopper?” So we jumped in Alex’s pickup truck. It took us a couple days. This truck did not run super well. We slept on the side of the road. We had no money. I remember Alex playing “Mexican Radio” on this cassette the whole time. It was driving me crazy.

We found out Dennis bought his booze at this liquor store, and we sat outside there for a while, but we never ran into him. Then we came back to L.A. and were able to set up a meeting.

Jonathan Wacks: He showed up all dressed in white. White shoes, white tie, everything white. It was weird. And some young woman on his arm. He kept popping vitamin pills throughout the meal. We thought he was perfect for that role. But Michael said, “Absolutely not, the guy’s got an addiction problem.”

Peter McCarthy: We all liked Harry Dean. He’s an amazing actor. He was at the very bottom rung of what Universal would accept.

Jonathan Wacks: A friend of ours worked at a pizzeria on Mulholland and told us Harry came and ate there every Thursday night, pizza and beer by himself. So we went on Thursday night, and lo and behold, there was Harry, and he was delighted to have someone to talk to. So we sent him the script.

Del Zamora: Abbe Wool was saying, “Harry Dean’s face is the face of America.” So I went to Alex and I said, “You should cast him. He has that weird craziness.”

Peter McCarthy: Harry Dean’s agent suggested using Mick Jagger. It was sort of amusing in a way. I’m sure Mick Jagger could have done it, but it would’ve been a really different film, but it wouldn’t have been the kind of film that it was.

Chris Penn (Sean Penn’s brother) was also briefly cast in Repo Man.

Jonathan Wacks: We were able to get Chris Penn to play Kevin. He was a friend of Emilio, and he wanted to be in the movie. But Alex was absolutely adamant that he wanted Zander Schloss to play Kevin. So I think Alex found some alibi in which to fire Chris Penn, and we brought on Zander.

Behind the camera, Repo Man scored auteur cinematographer Robby Müller, who’d built up a career working with German director Wim Wenders and had some time to kill before his first U.S. project.

Alex Cox: I wanted to have a guy called Steve Fierberg shoot it, but Nesmith didn’t like the cinematography. I was depressed, but Peter said, “Now you can ask for whoever you want. Who’s the best cinematographer in the world?”

Peter McCarthy: Robby was coming to the United States to do Paris, Texas. But he had this window, and he liked the script. And suddenly it was happening.

Del Zamora: I told Alex, “I noticed you never tell Robby where to put the camera.” And he’s like, “If you hire great artists like Robby, you let them be creative and then they make you look good.”

Peter McCarthy: He was a real character. We got him a little motel room in Venice by the beach. He didn’t drive, so we had to pick him up all the time. He was kind of a quiet guy. Very thoughtful.

Making the movie

“We did try to get product placement through beer companies and nobody wanted to do it because they thought the film was so off the wall,” Wacks says. “Then we went with the generic, and that sort of became a joke in itself.”

Everyone involved pretty much describes production as either an extremely efficient shoot, a nonstop party, or both.

Olivia Barash: I was on the set every night, which is unusual. It was like a family. It was a party, It wasn’t like anything I ever did.

Dick Rude: Sometimes we’d wrap pretty late in the morning around 2 or 3 a.m., and people wouldn’t want to go home. They’d sit around and have a campfire around the barrel. Harry Dean was always leading the charge. He’d pull out the acoustic guitar and hit the bottle or the beers and keep going.

Olivia Barash: Harry Dean Stanton would teach me Spanish love songs, and we’d harmonize.

Dick Rude: The people involved were having a good time creating art, and I think you really see it in the end product.

“I actually think the whole thing was the teamsters fucking with us.”

Peter McCarthy: We tried to save money by only having one Chevy Malibu. The teamster said, “You should have a backup car.” We said, “No, we can save like $3,000.” And then Alex didn’t have a car, so it became his vehicle.

On the second or third night of production, we had a meeting because we’re already two days behind. And the car gets stolen from right in front of the office. So now we don’t have the car, the main prop, so to speak, and we’re behind schedule. That’s why I started getting gray hair.

Del Zamora: When the car got stolen, it was amazing how Peter, Jonathan, and Alex didn’t skip a beat. They just adjusted on the fly.

Peter McCarthy: After we lost the car, we ended up getting another Chevy, and we were able to make it look like the original. Then the original was found somewhere. I actually think the whole thing was the teamsters fucking with us.

Various celebrities stopped by the set at one point or another. Some people recall visits from Tom Cruise (who had worked with Emilio Estevez on The Outsiders), but one celebrity who actually wound up in the movie was Jimmy Buffett.

Alex Cox: He was between activities and he just came to the set. So we put him in one of those CIA agent suits because he already had blond hair. He’s one of the guys setting fire to the body on the burning bench in downtown Los Angeles.

There were plenty of big personalities already on set and tension between them, especially when it came down to an explosive confrontation between Alex Cox and Harry Dean Stanton.

Alex Cox: I don’t regret working with Harry Dean.

Jonathan Wacks: Alex got into a fight with Harry Dean because Harry wanted to use a real baseball bat in one scene. And Alex wisely didn’t want him to do that. They got into a fight, a real fight.

“Robby Müller was afraid and wanted everybody to have plastic bats.”

Peter McCarthy: Robby Müller was afraid and wanted everybody to have plastic bats; I understood why Harry wanted to use a real bat. A plastic bat is just a whole other fake thing.

Alex Cox: Maybe it was a failing on his part to believe that in order to play an angry character, he had to become angry. I think there was a certain misinterpretation of the method.

Jonathan Wacks: Alex basically wrote him out of much of the end of the script and put Sy Richardson in a lot of those scenes.

Sy Richardson (plays Lite): I don't remember any of that.

“It was the L.A. River, and it was the factories, and nobody hung out down there.”

Los Angeles also became an integral character in Repo Man, for better or worse.

Dick Rude: I remember being downtown and making the film, and it was pretty much a ghost town at that time. It was the L.A. River, and it was the factories, and nobody hung out down there.

Peter McCarthy: We were shooting one day in the valley, the scene with the shootout in the liquor store. We even had two motorcycle policemen there. And while we were in that shootout, somebody came pulling into the parking lot and just started the car spinning around in the parking lot doing this crazy thing. I’m paying these police guys $400 each. And they’re like just sitting there with their mouth open. And I’m going like, “You’re supposed to protect us from stuff like this!” There was a lot of crazy stuff that I don’t know how to explain.

The ending

“There was a big debate about whether the ending should be apocalyptic or transcendental.”

Repo Man famously ends with the glowing Chevy Malibu flying up into the sky, but that wasn’t always the plan. The movie originally featured a more explosive finale that was scrapped at the very last minute.

Peter McCarthy: We had run out of money. We had run out of days.

Jonathan Wacks: The way the movie was supposed to end was that there is in fact a nuclear device in the trunk and they open the trunk and it explodes, and L.A. goes up in a mushroom cloud.

Peter McCarthy: We were originally going to shoot it at a Minuteman’s site, those silo sites where ICBMs were in the ground.

Alex Cox: We had it scheduled to shoot up on a helicopter pad up in the Santa Monica mountains overlooking the ocean. But we got fogged in, and the fog was so thick the helicopter couldn’t land. So we had to cancel the night of shooting.

Jonathan Wacks: Alex just threw his hands up and said, “Fuck it.” So I sat down with Martin Turner, the on-set photographer, at my house in Venice after every shoot and we wrote it. Everybody seemed to like what we came up with.

Peter McCarthy: There was a big debate about whether the ending should be apocalyptic or transcendental. It literally came down to location.

Olivia Barash: There were three different endings. Alex wouldn't tell us what we were doing until we were on set, which made it interesting.

Peter McCarthy: The glowing car, how do we do that? We got this stuff called Scotchguard and painted it with buckets of the stuff. The car elevating? Oh, my God, please. We had a crane. We were literally picking the car up.

“We got this stuff called Scotchguard and painted it with buckets of the stuff.”

At the last minute, Repo Man also almost managed to score what would have been a memorable cameo for the final scene.

Alex Cox: Vicki Thomas, the casting director, told me that Muhammad Ali was at Gold’s Gym in Venice. So I ran around the corner, and there was Muhammad Ali sitting with all these guys. I approached him and said, “I’m making this movie, and I’d like you to appear in the final scene of the film, which we’re going to shoot tonight.” And in a very soft-spoken voice he goes, “Listen, I’ve got a manager now and he says, whatever I do, I have to get paid a million dollars. So if you can organize this in the next three or four hours, then get back to me, and I’ll be down there.” And we shook hands and I called Nesmith and Universal. I tried to get them to authorize a payment of a million dollars to Muhammad Ali, but they wouldn’t pay.

Peter McCarthy: After the film was over, we did reshoots. Every two or three weeks, we’d go out for a long weekend. Alex ended up being the stunt driver in a lot of those.

The soundtrack

“San Andreas Records has only released one record, the Repo Man soundtrack.”

Music, and punk rock in particular, plays a vital role in Repo Man. The cast and crew all recall a lively punk scene in Los Angeles at the time, which bled into the movie and ultimately may have saved it from total obscurity.

Peter McCarthy: The music is what saved the film, so to speak, distribution-wise.

Alex Cox: The L.A. punk scene was burgeoning and very exciting. That was the aesthetic of the film. That was our aesthetic. We liked that music, and so it was inevitably going to be a punk score.

Peter McCarthy: If you lived in L.A. in the ’80s, the music scene was just unbelievable. I remember seeing early performances of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. You’d go into The Lingerie Bar and there’d be Flea.

Del Zamora: I got to meet all of them, and I was in videos for the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

“Something was going on in Los Angeles that wasn’t happening in New York.”

Jonathan Wacks: We used to go to the Elks Lodge, and there was a lot going on. X was big and Suicidal Tendencies and Fear.

Olivia Barash: There was a club — it wasn’t a club; it was a store in Westward — but they had Devo play there on Sunday afternoon.

Dick Rude: At the time, people hadn’t heard of Black Flag or the Circle Jerks or the Plugz; all the bands that we had on the soundtrack.

“People were buying the record, and they kept saying, ‘When’s the film coming out?’”

Alex Cox: Iggy had come out to L.A. because he knew something was going on in Los Angeles that wasn’t happening in New York. He’d come to find his rock and roll quest.

Olivia Barash: I was talking to Alex, and I said, “Who are you going to have do the title track?” And he goes, “There’s one of two people. David Byrne, we have something out to his agent. But I really want Iggy Pop, we just don’t know where to find him.” And I said, “I know where to find him. He’s in my building. He’s my neighbor.” So Alex came over, and we rang the intercom outside, and Iggy answered. And that’s how we got Iggy.

Peter McCarthy: His life and career was not going well. We got him relatively inexpensive for an original song.

Jonathan Wacks: We put together the album, and then we took it to Kathleen Nelson at MCA Records, which owned Universal.

Peter McCarthy: They end up setting up a whole new label called San Andreas. They kept saying, “Oh, it’s going to be this new indie label.”

Del Zamora: San Andreas Records has only released one record, the Repo Man soundtrack. They created it just for that.

Peter McCarthy: I recently saw an interview of a guy who worked at MCA, and he talked about setting up San Andreas for Repo Man. And he said, “The reason we called it San Andreas is because that’s the fault that runs right through California, and we thought was going to be a disaster.” And I thought, “Son of a bitch.”

Releasing the movie

“The theater was empty. That wasn’t good.”

Repo Man premiered in 1984 with very little support from Universal before eventually finding its audience.

Jonathan Wacks: The first release was a disaster. Universal put it out in Chicago, and nobody showed up. It was just pathetic.

Peter McCarthy: The test release in Chicago didn’t go the way they wanted it to go.

Del Zamora: We were there watching the movie to see what the audience thought, and they interviewed us for Siskel and Ebert. They didn’t know it was us. So we gave it eight thumbs up.

Jonathan Wacks: Our deal with Universal was that they had to release it in 12 major markets. So now they were going to just dump it in these different other markets.

Peter McCarthy: We hated the original poster from Universal. So we got about a hundred of them, and we spray painted our own design on it. Right before it opened in L.A. in May, we went out and pasted up the posters ourselves. We almost got busted. We got stopped in Venice Beach, but the cops thought it was so weird they let us be.

Olivia Barash: Me and Emilio went to Westwood to see it. It had just come out. The theater was empty. That wasn’t good.

“It starts playing in art houses in all the big cities, and it never stops.”

Peter McCarthy: Universal wanted to just put it out on VHS. Get some awareness and then get it to Blockbuster.

Dick Rude: But people were buying the record, and they kept saying, “When’s the film coming out?”

Peter McCarthy: Irving Azoff, who was the head of MCA records, wanted to know what the hell was with this Repo Man. “Where’s the film?”

Alex Cox: They started bugging management at Universal to bring the picture out. And that’s how it got a second life.

Dick Rude: That punk rock soundtrack really spread across the U.S. Suddenly, you weren’t a freak if you had red spiked hair.

“Suddenly, you weren’t a freak if you had red spiked hair.”

Jonathan Wacks: Universal had just hired a guy named Kelly Neal to re-release the Hitchcock movies one theater at a time. He knew the whole independent distribution scene. That was his thing. We played the movie for Kelly, and he loved it.

Del Zamora: It starts playing in art houses in all the big cities, and it never stops. It ran at the Nuart Theatre in L.A. for two years. They’d play it at 10 o'clock, and then at midnight, Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Peter McCarthy: Suddenly, it became an art film that everybody wanted to see. A film about our society and culture and the world and whatnot — and Alex's brilliant take on it as an outsider looking in.

Sy Richardson: I was living in an area called Antelope Valley in the mountains. I got up one morning and went outside to wash my car. And these three preteens looked at me and they said, “Hey, man, are you that dude in Repo Man?”

Dick Rude: It was sort of like a comet. The people who saw the comet wouldn’t shut up about it, and the people who hadn’t seen the comet really wanted to know. And so once it started hitting the VHS market, it really blew up and became cult status.

Peter McCarthy: We had a cast and crew screening at the Fox Venice Theatre. The night of the screening, I look outside, and there’s 500 people. Then there’s more. It’s growing all the time. People start banging on the glass doors. It looked like the glass was going to break, so they finally just started flinging open the doors, and they all just came rushing into the theater like crazy. That theater was so full. Every fire hazard in the world was being violated. And I remember turning to Alex and just going, “Holy shit, the buzz on this thing is unbelievable. How do you think they’re going to react to it?” And Alex goes, “I hope they rip the seats out and throw it at the screen. I just hope they rip the theater apart.”

“Repo World”

“Universal didn’t want any sequels.”

In the years since Repo Man’s release, Cox attempted multiple sequels with mixed results.

Alex Cox: The graphic novel Waldo’s Hawaiian Holiday was supposed to be the sequel. It was originally called Otto’s Hawaiian Holiday, and it was a sequel that I had written in the 1990s to make on the 10th anniversary of Repo Man. Jonathan and Peter and Nesmith were going to be the producers, and we all went down to L.A. and tried to convince Universal.

Peter McCarthy: We had a reading of the script at Harry Dean’s house. Emilio wasn’t sure if he wanted to be involved, but Willem Defoe wanted to be in it. I even had a poster made. But Universal didn’t want any sequels. And that’s why Alex, in doing Repo Chick, kind of just went “Fuck them, I’m going to just do what I want then.”

Poster art for an unrealized Repo Man sequel starring Emilio Lopez, Harry Dean Stanton, and Willem Dafoe.

Alex Cox: Repo Chick isn’t actually a sequel. It’s a story in the Repo World, but it takes place not in Los Angeles but on a model railroad layout. The characters are classic model railroad figures, like 7 or 8 centimeters high. It’s very Barbie in terms of its visual aspect, or I should say Barbie is very like Repo Chick.

Released in February 2011, Repo Chick has no official connection to Repo Man.

In February 2024, Cox officially announced plans for a direct sequel, titled Repo Man 2: The Wages of Beer.

Dick Rude: It was only in recent years that he got the rights back to the film. Around the pandemic, he and I started emailing back and forth ideas about doing another sequel or series.

Sy Richardson: I was reading it when you called. I like it, and I like the direction they went with it. I can’t talk too much about it, but I like it.

Alex Cox: The advent of incredible technology means, for the repo man, that everything has changed — and nothing has changed.