Primate Is A Big, Dumb Chimpanzee Slasher

For better or worse, Paramount’s latest horror offering is an unwieldy mix.

Right from its opening scrawl — which confidently asserts that rabid animals are “literally driven crazy” by the sight of water — Johannes Roberts’ Primate inserts itself into the grand tradition of moron horror. That’s by no means a bad thing. Half the fun of B-movies with A-budgets is stupid characters bumbling through fantastical scenarios en route to certain doom. Roberts’ Instagram-infographic-as-science approach helps establish his clockwork concept, in which a pet chimpanzee goes bananas on its teenage owners. The film is rife with tongue-in-cheek thrills and violent charms, as though that one scene in Nope were turned into its own feature. But it’s also strung together haphazardly, and wields hefty imagery and clashing tones it doesn’t quite know how to handle.

The idea is simple at the outset: what if a slasher/home invasion thriller starred an ape gone wild? An in-medias-res prologue teases ludicrous outcomes, as a happy-go-lucky ape caretaker (Rob Delaney) approaches Ben (Miguel Torres Umba) — a pet chimp clad in human smart casuals — in his private enclosure, and has his face viciously peeled from his bones. Between Ben’s practical costuming, and all the visceral blood and muscle, this intro promises a wonderfully tactile creature feature, on which it largely delivers.

However, when the film flashes back to 36 hours prior, and begins to focus on its human characters, things begin to drag. College-aged Lucy (Johnny Sequoyah) flies home to O‘ahu with her best friend Hannah (Jessica Alexander) and their overbearing, free-spirited acquaintance Kate (Victoria Wyant). Their plane ride involves banal conversations, which vaguely reference dramatic backstories that don’t amount to much. Lucy’s mother, a primatologist, has passed away, and Lucy hasn’t been back to Hawaii to see her younger sister Erin (Gia Hunter) or their Deaf author father Adam (Troy Kotsur) in some time. Back at their cliffside mansion, the teens catch up with Lucy’s attractive childhood best friend Nick (Benjamin Cheng) and with her loyal chimp companion Ben, whose casual presence in the modern triplex spooks the newcomer Kate — perhaps with good reason. He’s a little more aggressive than usual, thanks to a bite on his arm, but the family thinks nothing of it.

The girls just wanna have fun, while Adam is off on his umpteenth book tour, leaving them in the presence of the mysteriously injured primate. Hawaii is largely rabies-free, as Adam mentions over text at one point, so the possibility of something being gravely wrong doesn’t cross their minds. By the time Ben starts acting up — which is to say, when the teens’ swimming pool unlocks some primal instinct in him, like a CIA activation phrase — any attempts to calm the domesticated animal are too little, too late.

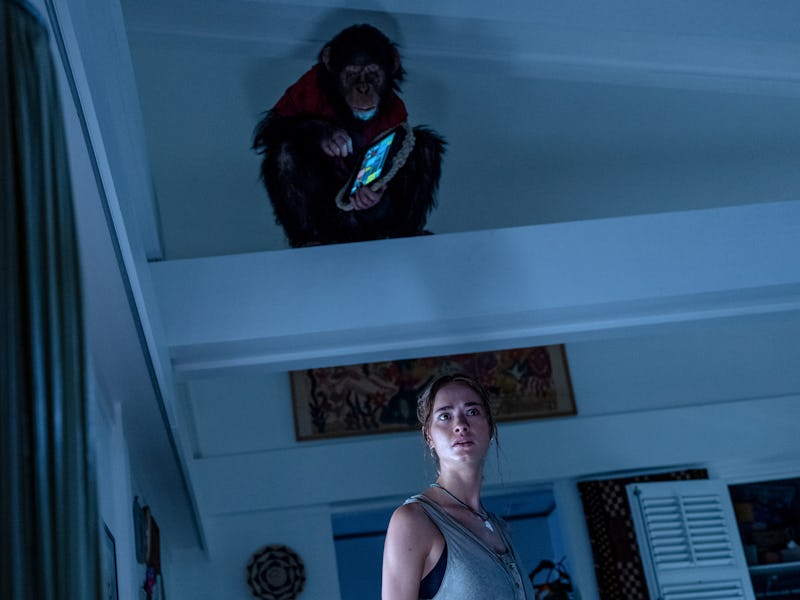

Ben and the teens, before all hell breaks loose.

The beginnings of Ben’s off-the-wall behavior are captured with visual flair: Roberts’ camera flips and rotates to reflect the ape’s madness setting in, like something out of the Twilight Zone. The advantage of having the teens be stalked by a familiar presence is that Ben can lurk in plain sight, adding a sense of unpredictability to Umba’s costumed movements, as cinematographer Stephen Murphy plays mischievously with visual focus. However, when things kick into high gear, and Ben begins to act less like a wild animal and more like a scheming secret agent — he scales walls and lighting fixtures, and shows up where you’d least expect — things start to get tonally iffy.

While introducing us to a more timid, pre-rabies Ben has the advantage of a gradual descent into “madness,” it also ends up positioning the poor, slobbering animal as an innocent victim of his own disease (and the carelessness of his owners), even though he ends up bloodthirsty and meticulous (a clear paradox, but whatever). The human characters are never three-dimensional enough to matter, nor are they offensive or bacchanalian enough to deserve their fates; they play by a more subdued slasher rulebook, committing the cardinal sins of LUST (some kissing), SUBSTANCE ABUSE (a joint) and CHAOS (a pizza box left open). This leaves Primate half way between a film that delights in its carnage towards its human characters, and one that tries to induce concern whenever they’re in danger.

The ensuing attempts at fun are colored by some strange visual tics that never quite settle. As the teens hide out in the family pool — hilariously, not because Ben has any real reaction to water, but because he cannot swim — they concoct various plans to get a hold of their cellphones and call for help, all of which go awry. But as they try to escape their dire circumstances, the movie loses its sense of geography and directionality. This occasionally leads to zany surprises, since Ben could be waiting around any corner, but it also obfuscates the thrills and stakes of its contained environment.

What’s more, Ben’s methodology when he gets a hold of his victims is also wildly uncomfortable. The way the ape mounts and pins his victims, and inserts his fingers in their mouths (not to mention, the intimacy with which all this is filmed) is reminiscent not of fights or animal attacks, but of distinctly human sexual assault scenes. Primate is, for the most part, an off-the-wall splatter movie filled with blood and bone, but it also introduces the specter of realistic sexual assault at random intervals, which really undercuts the enjoyment.

Primate has some promising ideas, some of which land, others of which do not.

There are distinct flourishes to be found, courtesy of the movie’s unique soundscape, but these are largely promises of a more interesting movie that wasn’t actually made. Kotsur, who won an Academy Award for his role in CODA, has a brief but congenial presence as a father caught between work and family, and each time he cheekily convinces Lucy to get closer to a boy, Primate approaches something resembling human warmth. That some scenes unfold in American Sign Language also separates the film from others of its ilk, and the fleeting moments of silence told from Adam’s point of view make for a uniquely engaging horror experience. But ultimately, not enough advantage is taken of this switch from sound to silence. The film’s acoustic quality isn’t so much “innovative” or “enrapturing” as it is reverential — and perhaps overly referential — thanks to a score that, bizarrely, takes on the (un)holy qualities of Jack Nitzsche’s music for The Exorcist, but without the prestigious sheen.

The visual compositions similarly riff on other classics (there’s a distinct shout out to The Shining, for instance), but none of these allusions ever enhance the story at hand, beyond signaling the film’s own shortcomings. At the end of the day, Primate is a horror romp filled with some fun ideas thrown at the wall — many of which stick — and some other heavily dramatic ones that severely misfire. In other words: It’s January, so you could do a whole lot worse.