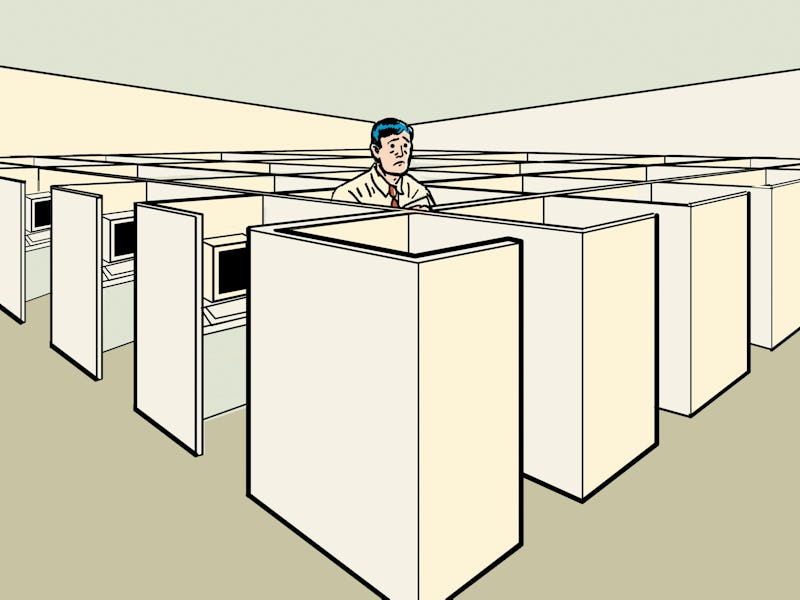

Could the much-maligned cubicle be making a comeback?

“The workplace will increasingly be called upon to provide what working from home cannot.”

There’s a scene in the classic 1999 movie Office Space where the increasingly carefree protagonist Peter takes out the screws from his cubicle and pushes down its wall, letting sunlight into his space. This scene may as well have been the death knell for the cubicle, which up until the ‘90s had been a staple of offices.

Many factors played a role in the fall of the cubicle, including the high costs of real estate to the influence of Silicon Valley office culture, but with open offices once again a source of ire among employees, will the much-maligned cubicle make a comeback? First things first, though, how did a private workspace used by medieval monks end up taking over America’s offices in the first place?

The problem

Workplaces in the early 20th Century resembled modern offices in one significant way: an open office plan. Yes, today’s biggest trend is not so new — you’d commonly find rows and rows of workers sitting side by side with nothing separating them, emulating factory assembly lines.

This original, spartan layout gave way to what the Germans dubbed the office landscape: desks grouped together by department and only separated from others by plants and room dividers. It was chaos, with plenty of noise and distractions. Concerns grew over the lack of privacy in these workplaces and the harm it caused to productivity.

"Today’s office is a wasteland," wrote Robert Propst, president of Herman Miller Research Corporation. "It saps vitality, blocks talent, frustrates accomplishment. It is the daily scene of unfulfilled intentions and failed effort."

The solution

Propst, ironically, invented the Action Office system in 1968 to save us from this open office "wasteland." As the precursor to the cubicle, the Action Office was "designed as a set of components that could be combined and recombined to become whatever an office needed to be over time." Propst worked with Jack Kelley, designer of the mouse pad, to create many of its components.

The invention caught on as an anathema to the messiness borne from open offices. Propst died in 2000, but two years before, around 40 million Americans worked in some kind of version of a cubicle.

"It gave office spaces more flexibility and versatility more than traditional walls would," said Verity Sylvester, co-founder of Branch, a venture-backed office furniture startup whose clients include Tumblr and SquareFoot. "Even back then, real estate was getting more expensive."

But the walls started closing in on the cubicle toward the end of the century. People hated them. They felt trapped in their workspaces and wanted space to breathe. Propst didn’t take this criticism laying down, placing the blame on companies that abused his creation.

"Not all organizations are intelligent and progressive," Propst said. "Lots are run by crass people who can take the same kind of equipment and create hellholes. They make little bitty cubicles and stuff people in them.”

Whether the criticism of cubicles was fair or not, their unpopularity allowed open offices to stage a comeback.

The evolution

As real estate has gotten more expensive, workspaces have been getting smaller and smaller, a trend that continues to this day. Nationally, companies dedicate about 120 square feet to each employee, a historical low, according to Sylvester. In New York, that average can be as low as 40 to 50 square feet.

“That’s shoulder to shoulder, essentially,” she said. “We’ve sold benches meant for four people [that customers] intended to use for six people.”

Of course, cubicles take up a lot of space and are expensive to install, but that wasn’t what sealed the cubicle’s fate. A lot of the credit (or blame) can go to Google. When the search giant established its office in 2005, it ditched cubicles for communal workspaces with some private spaces and meeting rooms.

“The workplace will increasingly be called upon to provide what working from home cannot.”

“The attitude was: We’re inventing a new world, why do we need the old world?” said Clive Wilkinson, the architect of the company’s Mountain View, Calif., headquarters. “We had [companies] come to us and say, ‘We want to be like Google.’ They were less sure about their own identity, but they were sure they wanted to be like Google.”

Now, about seven in 10 offices have an open floor plan. But echoing the past, these open offices have proven to be unpopular among the people working in them. Workers complain of an abundance of noise and distractions, according to SHRM. There’s a 62 percent increase in sick days at open offices, and most damning of all, a 70 percent decrease in face-to-face interactions with an increase in email use.

The future

This all seems like bad news for open offices, but it doesn’t necessarily indicate the cubicle will return. It just might mean that elements of the cubicle will be implemented into current open offices, especially as health becomes more of a concern.

“Individuals still value privacy and want their space,” Sylvester said. “Even three panels over their desks provide that. We’ve seen more and more clients requesting better privacy solutions. There’ll be some tradeoff between the flexibility of an open office and the cleanliness and privacy of the cubicle.” She's wary, however, of a cubicle comeback as people prioritize flexibility.

Colin Haentjens, a designer at The Knobs Company, agrees that personal space and cleanliness will be top of mind in the near future.

“Cubicles, or whatever the more palatable term is in the future, will be back in some fashion as long as business leaders listen to the desires of their employees,” he said. “They might have to financially rationalize it by understanding that more personal space leads to increased employee retention and fewer sick days.”

While it’s unclear what offices will look like next year, Chris Coldoff, principal and workplace leader at Gensler, said collaboration will take precedence.

“The workplace will increasingly be called upon to provide what working from home cannot,” he said. “Building community, reinforcing a company’s culture, and strengthening our relationships — with colleagues, clients, and partners — that’s what the workplace is and will continue to be all about.”