Freshman Congresswoman Calls Out US Health Officials for Gender Disparities

"I’ve seen the discrimination and institutional barriers firsthand."

In 2017, women in the United States earned 82 percent as much as men, meaning it would take women an extra 47 days to earn the same amount. A JAMA study published in early March revealed this financial discrepancy extends into the sciences, in the form of research grants. Men, on average, are awarded larger grants than women from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as first-time principal investigators — a difference that experts say places female scientists at a major disadvantage.

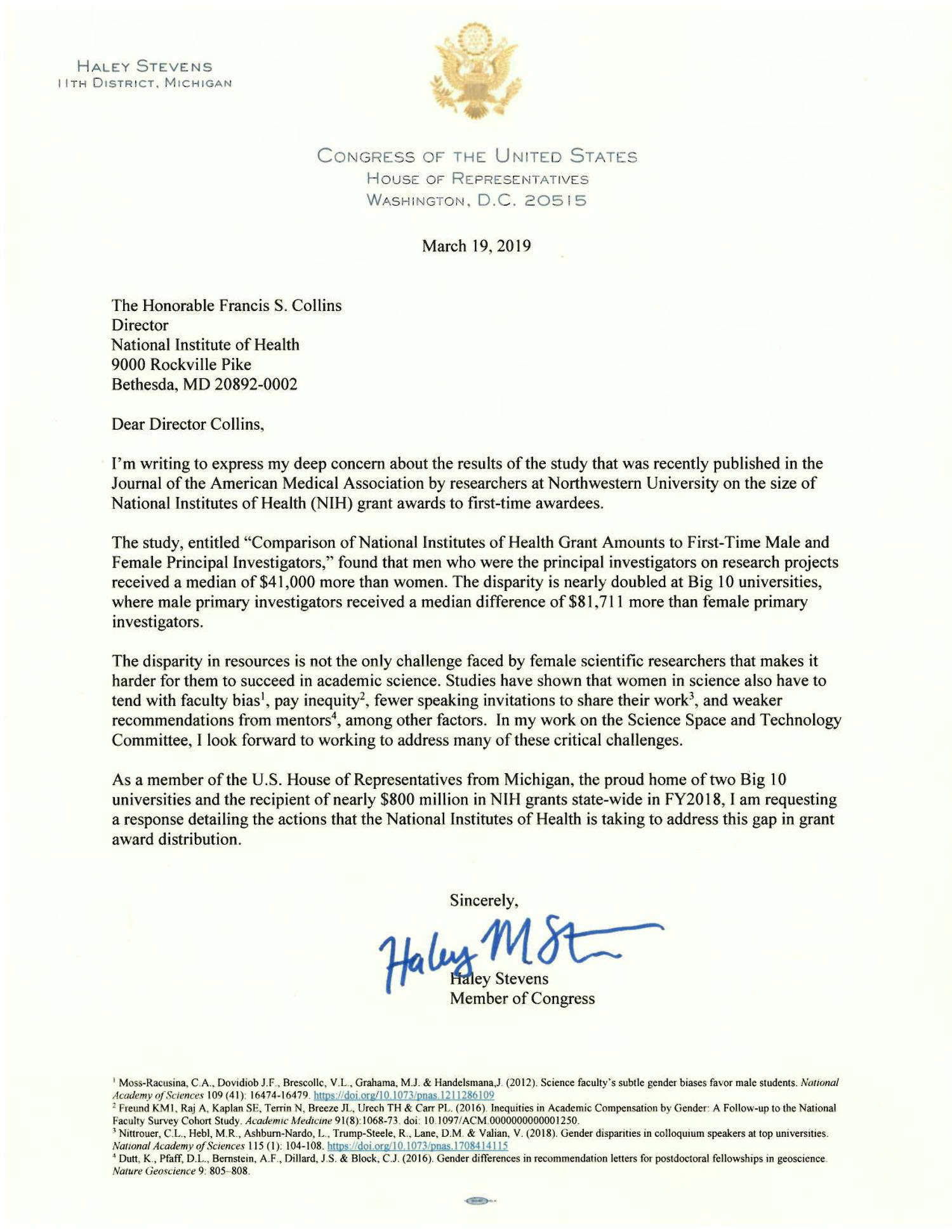

In response to this study, Representative Haley Stevens of Michigan is calling on the NIH to fix the problem. On Tuesday, Stevens, who chairs the House Research and Technology Subcommittee, sent a letter to the NIH expressing her concern. She requested a “response detailing the actions that the National Institutes of Health is taking to address this gap in grant award distribution.”

Before running for Congress, Stevens worked in a manufacturing research lab, and before that, she served as Chief of Staff to the US Auto Rescue and at the White House Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy under the Obama administration. She also launched a STEM education program that exposed 200 middle school and high school students to digital manufacturing concepts.

Because of her life experience, she tells Inverse, the issue hits close to home.

“As a woman in STEM, I’ve seen the discrimination and institutional barriers firsthand, and I know it’s holding our generation back from reaching that next great technological breakthrough,” says Stevens.

“NIH does incredible work, but the gender disparities in their grant funding must be addressed immediately.”

You can read the letter, which was shared with Inverse, below:

The letter is the second effort Stevens has made in March to bolster STEM efforts. Last Tuesday, she introduced her first bill as a member of Congress, the Building Blocks of STEM Act. One of the facets of the bill is an instruction to the National Science Foundation to financially support research on the factors that discourage or encourage girls to become involved in STEM and computer science.

The study in JAMA found that the median NIH award to first-time female principal investigators was about $126,000, while for first-time male principal investigators, it was $167,700. The researchers behind the study emphasized that receiving less money at the beginning of their careers means that women are less likely to succeed than men. With less federal funding, women can’t recruit the same number of grad students to work on their research projects, buy the same amount of equipment, or be seen on the same level as men.

It’s an open secret in the scientific community that the “right kind of grant” from the NIH means a researcher is more likely to be promoted, so a smaller grant early in a researcher’s career can directly hinder their long-term prospects.

The NIH has not disputed the study’s findings and says it is working to address this problem, as well as the overall issue of gender inequality in science. In a statement to the New York Times, the NIH responded to the findings: “We have and continue to support efforts to understand the barriers and factors faced by women scientists and to implement interventions to overcome it.”

Stevens is giving the medical research center a push to implement those interventions now.