"Catch-22 States" Face a Climate Change Food Crisis

This is scorched Earth.

Capitalism 101 suggests that countries should focus on producing things where there is a natural advantage and trade for the things where there isn’t. From this vantage point, growing food in the desert is downright foolhardy — better to concentrate efforts on drilling for oil and import your barley and wheat.

And yet, relying on world markets to supply things a population literally needs to survive is equally fraught. This is particularly true in a time of climate change, where shifting weather patterns are bringing droughts and pests to crops that are increasingly failing spectacularly, leading to conflict and war. In this new world, countries with poor agricultural resources are damned if they do, damned if they don’t — destined to either overstrain domestic resources for food production or rely too heavily on erratic international markets. This catch-22 is explored by Francesco Femia and Caitlin Werrell in Epicenters of Climate and Security: The New Geostrategic Landscape of the Anthropocene, a new report from the Center for Climate & Security.

Regions with high populations and low agricultural resources will struggle in a climate change future.

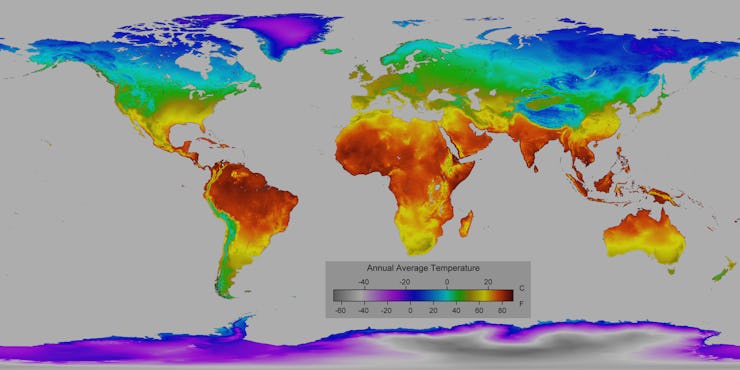

It’s not hard to identify catch-22 states at risk of future conflict; just look for the tan areas in a satellite image of the Earth. These highly desertified area in North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia are necessarily engaged in uncomfortable trade-offs when it comes to food.

The epicenter of this catch-22 risk is the Middle East. The idea that climate change will hurt crop yields and push strained countries to food wars is not some far off reality — it’s already happening and will continue to occur with increasing intensity and frequency in a world that keeps getting hotter.

Syria, plagued by brutal civil war since 2011, picked the nationalist route. Government policies shifted local production towards wheat, which kept people fed for the time being but pushed water resources to the edge. When droughts came, the wells had already run dry, and the government was ill prepared to manage an economically and physically starving population. Many blamed President Bashar al-Assad’s leadership for bad policy and shortsightedness, launching a fight for control of the country that continues to this day.

Egypt chose Option B — heavy reliance on imports to feed the people. In 2010 a heat wave and drought across Russia and China, made more intense by climate change, slashed global wheat production and saw bread prices jump 300 percent in Egypt. Protests already afoot in Cairo spread to the countryside, in part because of the extraordinary food costs.

Climate change doesn’t just make the world hotter. It shifts weather patterns, pests, and disease, and the net effect of all this change is that it becomes harder to produce food just about everywhere on the planet. As global warming intensifies, more and more countries will engage in this sort of catch-22, and they will fall deeper and deeper into it.