The Sex Robots Controversy, Explained

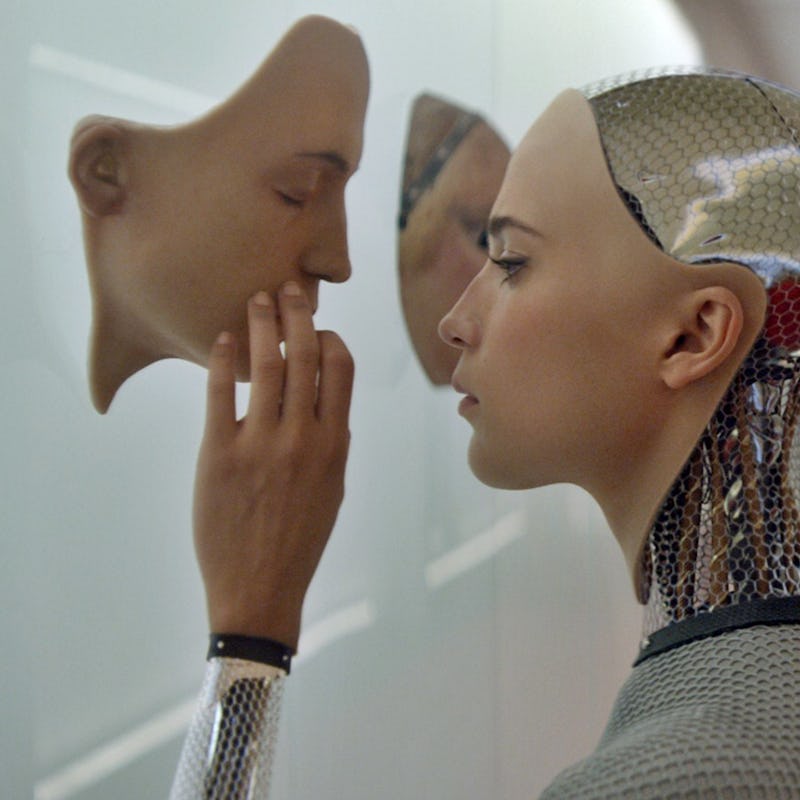

Can a robot ever gain consciousness?

Sex robots are coming. One futurologist believes that by 2050, sex with robots specially designed for human satisfaction will be the norm. Such a shift would represent a fundamental re-thinking of what sex is, our relation to robots in society, and what it means to give a machine artificial intelligence. These are big questions, and they’ve sparked an intense battle between pro- and anti-sex robot campaigners.

One group, the Campaign Against Sex Robots, is looking to educate the public on why robo-sex might not be such a great idea. The campaign was launched after its organizers presented a paper at Ethicomp 2015.

Girl on the Net, an anonymous blogger, writes about a range of topics within sex and sexuality. Last month, she responded to a tweet from the campaign that claimed humans couldn’t lose their virginity to sex robots. Girl on the Net responded by questioning the concept of virginity — drawing an arbitrary line around a very specific form of sex and referring to it as “losing virginity” is exclusionary, she argued, as it usually fails to account for experiences such as gay and trans sex.

But what is a sex robot? Simply put, it’s a robot designed for humans to have sex with. Early robots have focused on designs of women for men. TrueCompanion claims to have invented the world’s first sex robot, a female robot called Roxxxy. Later, the company introduced a male version called Rocky.

The focus on a very specific definition of sex robots, as women designed for men, is one that Girl on the Net feels misses the potential. “It’s really quite narrow,” she told Inverse. “I’m very keen on this idea that sex robots…can actually open up the discussion around sex that isn’t just man and woman.” There’s the potential for a vast array of specific machines, designed for a wide array of preferences and orientations.

TrueCompanion’s robot provides a basic level of social interaction, but it’s not clear that sex robots necessarily need to possess any emotional simulation to qualify. Futurologist Ian Pearson previously told Inverse, however, that the sex robots that exist today fall short of their potential as they lack sexual intelligence.

Kathleen Richardson, speaking on the ethics around sex robots at a TEDxULB event.

This drive to replicate human interaction is one aspect the Campaign Against Sex Robots objects to. “To me, it comes from an infantile fantasy,” Dr. Kathleen Richardson, head of the campaign and a senior research fellow in the ethics of robotics at De Montford University, told Inverse.

Richardson refers to The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, where a magician makes the broom come to life to make it carry out household chores, as an example of this “infantile fantasy” in media. Believing that inanimate objects can possess life of their own — animism — was a popular belief in medieval Europe.

“All we have is just a technological version of that,” said Richardson. “People think, oh it must be more true than it was in medieval times!”

This desire to attach human attributes to robots has been demonstrated in previous studies. Stanford University researchers found that participants recorded stimulation when asked to touch the areas of a robot that would be considered intimate on humans.

“The genuine desires that people have for connection are being warped by how we’re starting to think about sex today as a commodity,” Richardson said. “Not something that’s relational between persons, but as something that’s more shaped by sex trade, and that gets filtered more into the ideas of sex, and how they impact society.”

Girl on the Net argues that this aversion to sex as anything other than an emotional connection is one of the campaign’s major issues. Prostitution, or sex work, is an intensely-debated topic with a range of voices on both sides. Where Richardson sees sex robots as part of a wider commodification of sex, Girl on the Net rejects the conflation. Sex workers should always have the ability to consent and choose clients, something robots lack.

“When you dig a little bit deeper, it sounds like a lot of what the campaign believes is that any sex which is not loving…it’s not a religious argument, but it’s that kind of conservative, sex should be between two people who love each other very much, type of thing,” said Girl on the Net.

As time goes on, it becomes clearer that there’s a wider schism between the two arguments. On one side, there’s a belief that humans could develop consciousness (or something that resembles it) and place it inside robots, whereas the other side sees it as a dangerous confusion.

Richardson rejects what she describes as a modern animism. “Consciousness is a property of life, so you have to be living, but it’s also species-specific,” she said. “I do think it’s a property of being a living being.”

Girl on the Net argues that attaching attributes to robots previously reserved for humans does not necessarily come with any harm. Using robots for sex won’t mean that we stop caring about real peoples’ thoughts and feelings.

“Actually, the fact that this conversation is happening at all shows that we do care!” Girl on the Net said. “We can’t help but theorize about what people might be thinking and empathize with how a robot might be feeling.”

Accepting the idea of programmable consciousness raises ethical dilemmas that otherwise wouldn’t exist. Girl on the Net argues that if we develop robotic consciousness, not only would it be unethical to program them to be sex robots, but it would be unethical to program them to do anything.

“If we build a robot that can make choices and have free will, then we’ve essentially built a robot that can consent,” Girl on the Net said.

Assuming we could make robots with a simulation of consciousness, it could be unethical to make a robot without that consciousness, as it’s a conscious act to not give it that option of consent. On the other hand, if the robot never had a consciousness, perhaps there is no moral dilemma.

Rejecting the dilemma outright, Richardson sees the conflation as part of the “extreme neoliberalism” of Silicon Valley, to want to break down the barriers between humans and machines. Once you reach the point where you accept robotic consciousness, possibly the defining feature of being human, what’s left? “Everything is a potential commodity,” she said.

It’s a difficult discussion, mainly because of the number of questions both sides raise. Does empathizing with robots mean the next Zuckerberg could try and sell our emotions to us, or is it something we already do without the tech world’s help, so accepting it can help us better understand ourselves? There are no easy answers, but if Pearson is to be believed, it’ll be decades before sex robots reach the market.