5 Horrifying Revelations From the 'LA Times' Massive OxyContin Investigation

The drug company's claim that the painkiller lasts 12 hours was motivated by profit, not evidence, and consequences for public health have been disastrous, according to the report.

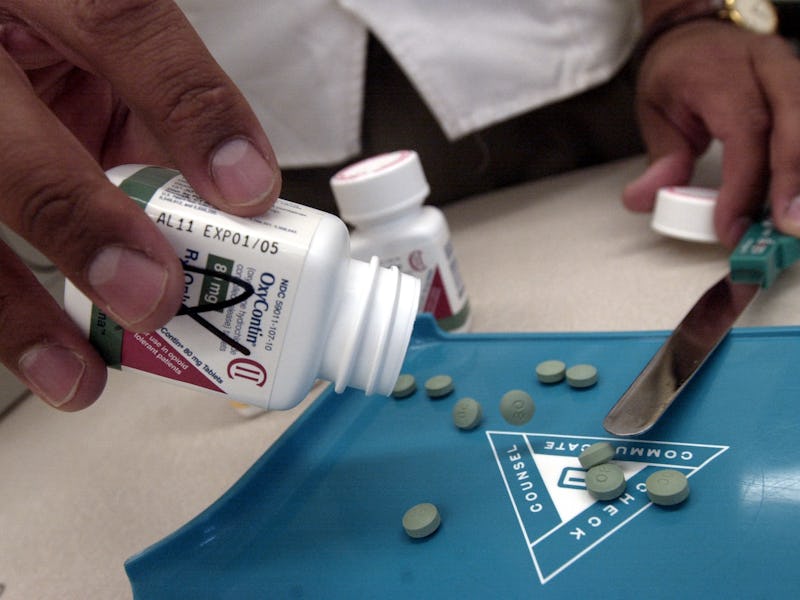

The Los Angeles Times dropped a bombshell of an investigation today, blaming Purdue Pharma for fueling an epidemic of prescription drug abuse by insisting that its OxyContin painkiller lasts at least 12 hours, despite evidence to the contrary.

The full report (with more surely to come) is worth every minute of your time. It contains extensive documentation, as well as the heartbreaking stories of several people who were prescribed OxyContin for pain relief, only to find that pain and withdrawal symptoms that surfaced before they were due for another pill left them contemplating suicide.

In a one-page response to the Times, Purdue noted that OxyContin had been FDA-approved for 12-hour dose intervals. “Scientific evidence amassed over more than 20 years, including more than a dozen controlled clinical studies, supports FDA’s approval of 12-hour dosing for OxyContin,” according to the statement.

Definitely go read the whole thing, but if you need to get up to speed quickly, here are the highlights, or lowlights:

Purdue knew that OxyContin didn’t last 12 hours for most patients, based on its own clinical trials.

In one clinical trial in cancer patients, 95 percent needed “rescue” painkillers to get them through to the next dose, according to the Times report. In another, where rescue medications were not permitted, a third of the patients dropped out because they found the treatment ineffective. The FDA approved the drug at a 12-hour dose based on one clinical trial where barely half of patients got through the 12 hours without requiring additional painkillers. The FDA official who led the review left the agency shortly thereafter, and within two years was employed by Purdue in new product development.

Despite this, Purdue aggressively marketed OxyContin as a 12-hour drug

“Q12h,” which is doctor-shorthand for “take every 12 hours,” was at the center of the OxyContin brand, the Times alleges. The logo was emblazoned on clock and fishing hats that were gifted to doctors by sales reps for the drug. “Remember, effective relief just takes two,” read ads in medical journals, accompanied by a photo of two dosing cups, one labeled 8 a.m. and the other 8 p.m..

The twice-daily dose was Purdue’s main competitive advantage over generic painkillers — without it there would be no reason to pay hundreds of dollars a bottle for brand-name OxyContin.

Pharma reps told doctors to prescribe higher doses, not more frequent doses, when patients complained of effects wearing off.

When doctors began prescribing doses every six or eight hours to patients who complained that effects wore off, as is common for other painkillers, Purdue fought back aggressively, the Times investigation found. Sales reps told doctors to prescribe higher doses instead of more frequent doses. This was the headline of a memo to Tennessee sales reps, reminding them that higher doses are the key to a bigger payday:

“$$$$$$$$$$$$$ It’s Bonus Time in the Neighborhood!”

The problem with higher doses is that it doesn’t necessarily prolong the effects. In fact, it can give the patient a higher high and a lower low, strengthening the incentive for them to take pills more frequently than prescribed. It could be “the perfect recipe for addiction,” on researcher told the Times. Higher doses increase the likelihood of overdose and death.

Purdue and other drug companies intentionally and successfully expanded prescription narcotics beyond the end-of-life care market.

Before OxyContin came on the scene, narcotics were mainly reserved for cancer patients and palliative care, because of their strong potential for abuse. “We do not want to niche OxyContin just for cancer pain,” a marketing executive said at a 1995 meeting, according to minutes reported by the Times. The push worked, and other drug companies elbowed their way into the game, too. By 2010 one-in-five doctor’s visits where pain was the main complaint resulted in a prescription for a narcotic painkiller.

Today, more than half of long-term OxyContin users have been prescribed dangerously high doses.

According to an analysis of insurance claims for about seven million Americans, 52 percent of people on OxyContin for more than three months in 2014 were taking more than 60 milligrams a day. That’s a level that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tells physicians to either avoid or carefully justify, because of the potential for overdose. Doctors wrote 5.4 million prescriptions for OxyContin in 2014, and 80 percent of those called for 12-hour dosing.