Dr. Charlie Hunnam, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Television

I was in pain and I was alone -- except I wasn't.

I watched from my couch as Charlie Hunnam smashed a guy’s skull with a snow globe, its lullaby tinkling pleasantly as blood stained his blonde hair. My position was precarious and uncomfortable, that of a mountaineer descending a peak of ice packs and pillows. I’d been stuck there for a while, clicking back and forth between murder and mayhem on TV.

Two months into my recovery from back surgery, I couldn’t do much but lie uncomfortably still. Scoliosis curved my spine 20 degrees by the time I was 10 years old. Many people have curves of 8 to 10 degrees and live perfectly normal lives. 20 is the point at which doctors get concerned. Though I went through puberty in a back brace, my spine never got the message. In college, I had the wheeze — if not the casual cool — of the smokers, my unearned pack-a-day breathlessness a product of pressure from my vertebrae on my lungs. By the time I graduated, my curve was 58 degrees.

The situation needed fixing, so I went to a surgeon who described his plans to suit me up like Wolverine. He’d cut me open neck-to-waist and bring my spine in line with titanium rods. My doctor gave me pamphlets about the procedure and recovery, but I ignored them out of a stubborn refusal to acknowledge that this was happening.

In retrospect, I’m glad I did. Had I known what my hospital stay would involve or that I’d spend the next year with fictional blood-soaked characters, I might have said, “let’s just chance that lung compression thing.” Had I known that Jax Teller and Charles Vane would become significant parts of my life, I would have asked, “who the hell are they?”

If body trauma and recovery taught me one lesson, it was how pain strips away at your identity. If it taught me a second, it was how distraction — and specifically television — can tether you to sanity.

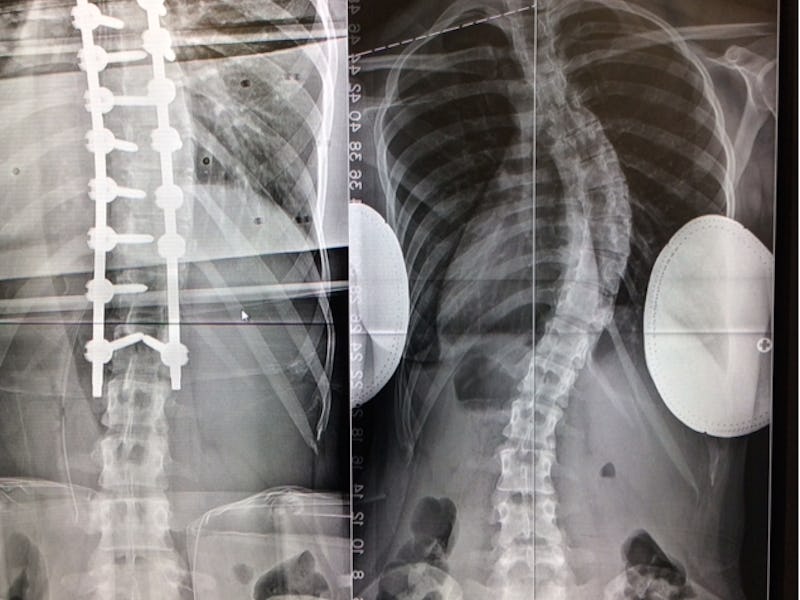

Me pre-surgery. I'm not leaning -- that is what standing straight looked like

I thought I’d at least be able to distract myself with books during my hospital stay. The first clue that wasn’t going to happen arrived in the form of vomit. When my nurses wheeled me to my room, that small movement made me as nauseous as if the bed was a boat in storm-tossed waves. Then I fainted from the the spine-shredding, ribcage-stabbing pain of puking.

Narcotics, it turns out, don’t agree with me. I couldn’t keep food down post-op. I was too weak to stand on my own, so I peed only with assistance from a bathroom sherpa. The books I’d asked my mom to bring (the Harry Potter series; my favorite Margaret Atwood novel) sat untouched. I couldn’t pick them up or focus.

Outside in the real world, my friends were starting new jobs, going on dates, backpacking to exotic places. I was learning what it felt like to want to molt like a snake and trade your body for another. On the Fourth of July, I spent hours locked in a cycle of puking and squirming in my hospital bed because — since I couldn’t keep the pain meds down — being in a position for longer than two minutes was excruciating. I looked out the window hoping to catch a glimpse of fireworks, but the act of turning my head made me so dizzy I threw up again.

When I left the hospital paler, scarred from waist to neck, and thinner-haired from the stress, I needed to get out of my reality; it made me the perfect target for cable television.

I'm a cyborg.

When you break your wrist, you can throw a baseball again after a couple months. When doctors screw 20 titanium bolts in your spine, it’s a full year until you can function in a manner approaching normalcy. I wasn’t allowed to bend, twist, or lift anything, and sitting upright for long was uncomfortable.

I couldn’t watch TV for the first month; the Oxy rendered me unable to look at screens without feeling vertigo. (Seriously, how are people addicted to that? Coke and heroin at least make you feel good, and meth is in vogue thanks to Breaking Bad). But once I was downgraded to regular painkillers, I self-prescribed television.

Previously, I’d always treated it as a social activity: I discussed Game of Thrones with friends; quoted It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia with my brother. But during my recovery, I found myself more isolated than ever before. Friends visited occasionally, though I wasn’t sure if that made it better or worse. I didn’t want to be a bummer, but because I was doing nothing all day, I felt like I had nothing to talk about.

In my copious alone time, I got sucked into two shows no one I knew watched: Sons of Anarchy (biker Hamlet) and Black Sails (pirate Deadwood). While most people my age spent weekends at parties, Saturday nights saw me spending quality time with Charles Vane and James Flint while they snarled at each other. When Charlie Hunnam, in the leather kutte and biker boots of Jax Teller, pondered his late father’s legacy, I pondered it too.

I didn’t realize the irony until later: That after being violently torn open and put back together, I found my escapism in blood-spattered knuckles, motor oil, and the brine of the sea. (For the record, I get seasick, have no particular inclination towards motorcycles, and a low tolerance for gore). There’s more to each show than that, but the main allure was that they were dramatically different from my reality.

Both were also shows I would have overlooked at any other time: Black Sails had an uneven first season, Sons of Anarchy had a lackluster final three seasons, and I had no one to discuss either with. But the former is still ongoing, and I find myself even more devoted to it than my other pop culture followings, because it will always be special for helping me get through this time. Also because it’s actually great and I stand by that.

At the time, I struggled to stand by anything. I couldn’t even open my parents’ fridge. The metal in my back wasn’t fully fused yet, and I could feel it with every movement, like I was a human version of a half-played game of Jenga.

Months later, when I started physical therapy, the therapist’s assistant also watched Black Sails. I had been apprehensive about therapy, in part, because it involved interacting with strangers for the first time in a year — and I was rusty with my people skills, having lived as a shut-in — but lo and behold, the machinations of Nassau eased the way.

Me mid-recovery with my cane and pillow mountain

Thinking “there’s always someone who has it worse” is not as helpful as I was led to believe. On one hand, it can help you keep things in perspective. But it can also give you cause to dismiss your own pain. Any time I felt down, I would immediately feel like an asshole. Wouldn’t someone who is a permanent invalid be disgusted if they saw me moping? Be envious I would eventually be mobile again?

I was lucky my parents even had a couch for me to recover on, lucky they had insurance, lucky this was not a permanent situation, but a strange and terrible sort of tourism into a very different kind of life. Even though it was unwilling tourism, to indulge in negativity felt like I was stomping over someone else’s territory. Armed with a fancy camera, a shell necklace, and a garish floral shirt; telling the natives I totally understood their plight and somebody should really help them.

I can’t presume to speak for others who are rendered less mobile, whether it’s permanent or temporary. But television was my lifeline, and in a strange way, my social connection. When my friends came by, I felt like I needed to perk up so my low spirits weren’t contagious. But Jax Teller and Charles Vane and the rest didn’t know I fucking existed, because they didn’t. In spending time with them, I could alleviate my sense of isolation without having to pretend to be handling this with grace. They didn’t care much for social graces themselves — and unlike real people, they required nothing from my end.

Drugs take you out of your mind temporarily, but there’s no limit to the time you can spend engaging with stories. When you’re in a state like this, fiction is your second kind of tourism. The welcome kind.

Day 1 home from the hospital����

When a person is deeply invested in a fictional world, it can be hard to gauge the nature of their relationship with reality. There’s a reason the token response from those who don’t understand is, “Get a life.”

But during this time, these shows were my life, or at least more favorable alternates. As I lay on my couch between cane-assisted strolls around the block, I sailed the open seas with the crew of The Walrus and The Ranger and traveled the California highways with SAMCRO. For an hour, a day, a week, I could be distracted from my pain-laden body and listless thoughts. I didn’t get to be someone else — I wasn’t drugged up enough for that — but I got to be somewhere else. And that mental relocation mattered. “All the world’s a stage” is particularly resonant when your world is a couch.

Recently, I consulted with someone who is an expert in a show I cover for work. She lives and breathes it more than anyone I know, and most of her free time is dedicated to dissecting it. In the past, I might not have felt like I could relate to her, simply because she lives her life on a different level of engagement than I did. But now? I can’t pass judgement; I don’t know what needs this show is fulfilling in her.

If you watch too much TV, you should probably get outside and smell the roses. But that doesn’t negate the fact that it can offer something essential to those who have need of it. The notion that only critically-buzzed about prestige dramas matter is foolish: Any show that someone cares about matters, because it matters to them. Except if you care about the Kardashians — then I’ll still make a polite excuse and back away. My experience didn’t change me that much.

The before (right) and after (left)

After spending so much time inside with fictional characters for company, it was jarring to re-enter the world at the end of that year. My status as a “regular person” felt like I was playing a part on a show for which I hadn’t received the script.

On the Fourth of July, exactly one year after my worst day in the hospital, I went to a friend’s party. It was nothing out of the ordinary: burgers sizzling on a grill, sun-soaked conversation, beers. On TV, it would be cued with a trendy score and it would be a perfunctory, forgettable scene. Shiny Young People Being Shiny and Young; as pretty and vapid as a moving Instagram. To me, it held the utmost significance, because it marked how far I’d come.

A few friends at the party were among those who visited me that year. I thanked them for spending time with me when I couldn’t move much and talked too much about pirates and bikers. They seemed bemused. “It wasn’t a big deal,” one said. And for him, it wasn’t. It might have been my A-Plot, but stopping by to see me wasn’t even B-Plot material for him.

I didn’t know how to express, without getting weird and sappy, how big a deal it was. How much it meant; how I’d never forget it. To be lonely — whether it’s induced by situational isolation like my recovery, or whether it’s induced by something else — is to be at the bottom of a well. When you look up to the glimmer of its surface, it seems insurmountably far away. During that year, my friends and family were above, bathed in the light of normalcy. For all they cared, they couldn’t truly understand my circumstance, and I had no desire to drag them down with me.

Everyone who finds themselves down that well hopes for different kinds of help. For me, the bucket on the string came from bikers and pirates. I’ll always be as grateful to them — and the people who create them and play them — as I am for the family and friends who cared. If you can find the right mental vacation, no matter how ridiculous it might sound to someone else or even to your former self, the well’s depths don’t have to be dark and dull. Sometimes, the rope you need to climb out plugs straight into the cable box.