A private mission wants to find alien life on the Solar System's most unrelenting planet

The Venus Life Finder mission wants to find microbes on the place they shouldn't be able to survive.

The last mission to enter the mysterious cloud layers of Earth’s superheated twin Venus was long enough ago that it was launched by the Soviet Union, a country that no longer exists. Vega 2 spent two days floating through the clouds in the summer of 1985, and its lander survived for 56 minutes on the unrelentingly hostile surface.

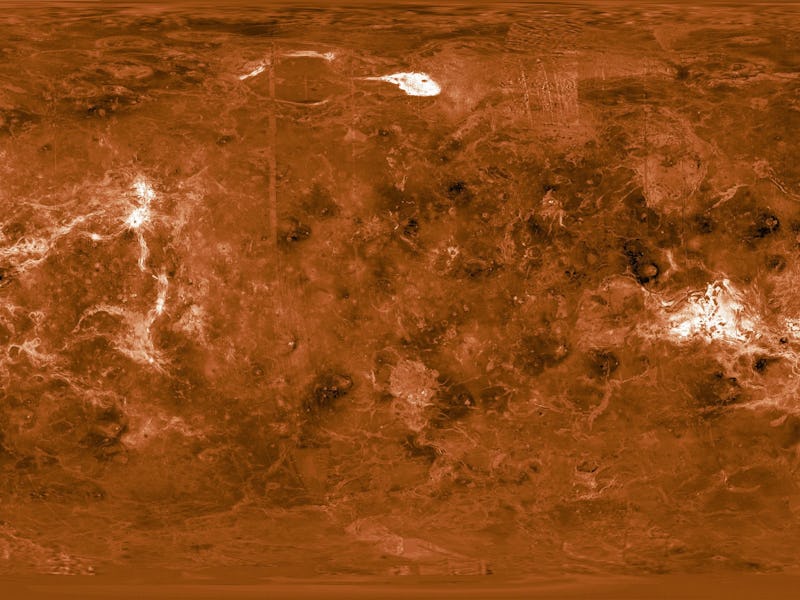

Since then, missions to Venus have remained in the comparative safety of orbit. The last American mission to visit Venus itself was the Magellan, which visited in 1989 and hung out until 1994. But that will soon change.

While NASA has plans for VERITAS and DAVINCI+ to orbit Venus and for the latter to drop a probe into its cloud layers, a privately-funded mission to Venus could chase a controversial 2020 discovery indicating microbial life in the upper cloud layers of Venus.

The Venus Life Finder Mission team, based at MIT, wants to send a small, single-instrument probe to descend through the clouds that permanently huddle over Earth’s nearest neighbor next May, according to the team’s latest mission summary.

WHAT’S NEW — Venus Life Finder team proposes three increasingly complex missions, with the first already prepared in collaboration with Rocket Lab. (Rocket Lab CEO Peter Beck spoke with Inverse about his interest in the planet in 2021.)

The “small mission,” as the team refers to it, involves sending an instrument known as an autofluorescence nephelometer (really rolls off the tongue) plummeting through Venus’ three layers of clouds to look at the makeup of the clouds. The instrument will shine an ultraviolet laser into Venus’ atmosphere and watch it pass over the particles that fly by.

Artist’s rendering of the Venus Life Finder fleet and what it might look for

According to Janusz Petkowski, an astrobiology researcher at MIT and deputy PI on Venus Life Finder, “many atmospheric anomalies have accumulated over decades from the time of Pioneer-Venus and Venera from the Soviets,” from the presence of ammonia and oxygen, to non-spherical particles in the clouds that might be salts, to the controversial presence of phosphine first announced in 2020. Venus Life Finder’s mission would mark the first direct observations of the cloud layer in nearly four decades.

Petkowski says Venus Life Finder will give scientists a chance to determine which of those anomalies are actually present in Venus’ atmosphere — or “maybe even discover some new anomalies in the process.”

MIT astrophysicist and Venus Life Finder principal investigator Sara Seager tells Inverse, “if there’s ringed carbon molecules they’re very easy to fluoresce. And that would be really a big breakthrough. It doesn’t tell us if there’s life there, but if there’s organic molecules it means there’s organic chemistry, and that would definitely be a step in the right direction.”

The tight focus of this mission means that the question of phosphine, which drew the team together during the pandemic, will have to wait for subsequent missions. Current plans call for a medium and a large follow-up to the nephelometer. A medium mission would involve floating a balloon through the harsh clouds for several days.

The more ambitious large mission would involve returning a Venusian sample to Earth. These missions have a much longer timescale, and rely on other parts of the community to solve critical engineering problems – like NASA’s Mars Sample Return, scheduled to collect Perseverance’s samples sometime after 2028.

A panorama of images from Venera 13.

WHY IT MATTERS — Since the last time probes visited Venus’ atmosphere, Seager says, “there’s this quiet revolution happening about thinking about Venus as a habitable environment.”

“Most of our life's biochemicals can’t survive in it, it was kind of the accepted wisdom that it was sterile,” she adds.

But laboratory experiments have begun to demonstrate that even an environment made up of sulfuric acid is not necessarily anathema to complex organic chemistry, or even life.

“Our organic chemistry might not be able to survive it, but that doesn’t mean that all organic chemistry is impossible,” Petkowski say. Finding organic molecules in Venus’ clouds would be the first step toward determining if there’s a rich hydrocarbon chemistry within the clouds.

Additionally, some of the anomalies observed by previous Venus missions point to the potential for much more habitable spots within a planet that is still hostile to life. The presence of ammonia would mean that “the clouds are not exactly what we think they are,” Petkowski adds, and that while Venus overall is extremely dry, local measurements from Pioneer and the Soviet Venera probes indicate that there may be local patches where there are anomalously high amounts of water. “Venus’ clouds are a Pandora’s box — each time we dive into the old data collected by the Americans and the Russians we discover there is much more to the clouds than we actually thought and they are much more mysterious than we previously thought.”

WHAT’S NEXT — NASA and the European Space Agency each have missions planned for the end of the decade. But if it launches on schedule in May of 2023, Venus Life Finder would be the first privately-funded scientific mission to another planet. “This is kind of the opposite approach,” notes Seager. The mission would launch aboard a Rocket Lab vehicle, marking that company’s first interplanetary mission.

Compared to these larger, multi-mission probes, VLF’s first mission has only one instrument, and one focus as a project: determining if there is organic chemistry in Venus’ clouds. “Instead of waiting 10 years or 40 years to go back to the atmosphere of Venus, we’re trying to do things that are focused–but still very expensive–missions that can answer questions sooner,” Seager says.

The team hopes that Venus Life Finder’s small first mission will inspire a new focus on Venus’ present, not just its past. Notes Seager, “The search for life on Venus is taboo, still kind of crazy, and despite people having thought of this half a century ago starting with Carl Sagan, it’s kind of out there. And so there’s a real niche for small focused privately funded missions to fill because there could be something big there, but if people are too conservative to search for it, it leaves an opening for a new way of doing things.”

This article was originally published on