The Gulf of Mexico "dead zone" is the worst science summer ritual

A new NOAA report forecasts the 2020 dead zone.

While summer 2020 is shaping up to be a very distinctive summer, one annual environmental event is back with unfortunate regularity. According to a new report, the "dead zone" that forms every year in the Gulf of Mexico is forming, and this year it's expected to be "larger-than-average."

A dead zone, or hypoxic area, is an area of low to no oxygen where marine life struggles to survive. It's often caused by an algal bloom: Too many nutrients in the water cause algae to flourish beyond its normal levels, which chokes out fish and other animals, eventually killing them.

In the Gulf of Mexico, a massive low-oxygen area forms every year — it's the world's largest recurring hypoxic, or extremely low-oxygen, mass. It's been happening since at least 1950 when it was first noted by shrimpers in the area. This dead zone equates to 4.3 million acres of potential habitat loss for fish and other animals.

On Wednesday, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Organization (NOAA) released its latest report, a forecast of the 2020 dead zone.

NOAA scientists predict an above-average dead zone that spans about 6,700 square miles, according to the report. This prediction is based on river-flow and nutrient data collected by the U.S. Geological Survey.

While this is larger than the average of 5,387 miles, it is much lower than the biggest on record. In 2017, the dead zone spanned 8,776 square miles.

The dead zone is bad news for marine life, and for fishers who rely on a healthy fish population to make a living. The Gulf of Mexico supplies 72 percent of shrimp harvested in the US, 66 percent of oysters, and 16 percent of commercial fish overall.

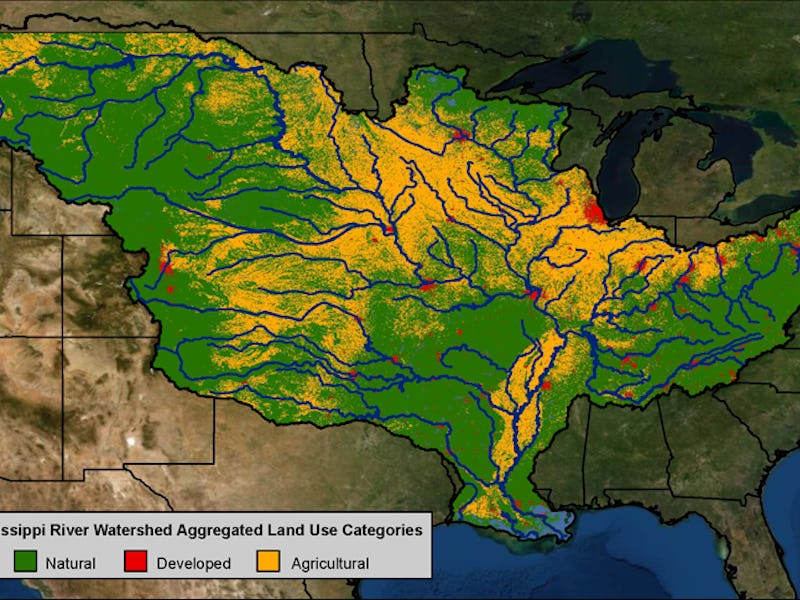

NOAA reports on land use along the Mississippi River.

“Not only does the dead zone hurt marine life, but it also harms commercial and recreational fisheries and the communities they support,” Nicole LeBoeuf, acting director of NOAA’s National Ocean Service, says.

“The annual dead zone makes large areas unavailable for species that depend on them for their survival and places continued strain on the region’s living resources and coastal economies.”

Why does the dead zone happen every year? — As the Mississippi River runs throughout the United States, it picks up excess fertilizer from farms. Then, at the point where rivers run into the Atlantic Ocean, that fertilizer — as well as treated wastewater — is pushed into the Gulf of Mexico.

That pollution contributes to eutrophication, a spike in nutrients like phosphorous and nitrogen. In turn, those nutrients stimulate algae overgrowth. Decomposing algae deplete oxygen as they sink to the ocean floor and, as a result, life can't thrive in the bottom layers of the Gulf.

"Fish, shrimp, and crabs often swim out of the area, but animals that are unable to swim or move away are stressed or killed by the low oxygen," the USGS website states.

In order to curb this effect, groups are working to reduce the number of nutrients that end up in the water. By targeting where exactly the pollution is coming from, groups like the Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force hope to shrink the size of the dead zone over time.

They have a specific goal in mind: reduce the size of the dead zone to a 5-year average of 1,900 square miles. Researchers also suggest limiting the pollution that enters waterways by:

- Using fewer fertilizers, and changing the timing of fertilizing farmland, to limit nutrient runoff

- Controlling animal waste to prevent it from entering waterways

- Monitoring human septic and sewage systems to reduce nutrients entering groundwater

- Regulating industry to limit the discharge of nutrients, organic matter, and chemicals from manufacturing plants

NOAA will confirm the official size of the 2020 dead zone in July.

This article was originally published on