Scientists capture ‘twisted’ jet erupting from black hole in unprecedented detail

It took a virtual network of telescopes around the world to get this image.

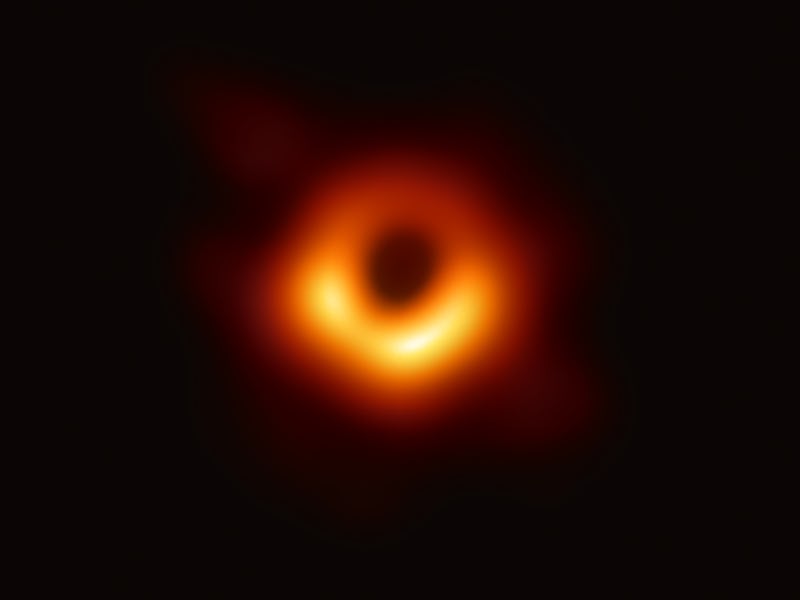

On April 10, 2019, the world got its first glimpse at a blackhole, revealing the massive cosmic being surrounded by a bright halo of light and presenting the strongest evidence to date of the existence of supermassive black holes.

The same telescope used to capture the iconic image has now gotten a rare glimpse at a powerful jet of plasma shooting out from near a supermassive black hole that’s about one billion times the mass of the Sun.

The Event Horizon Telescope, a telescope array that combines the power of various radio satellites ranging from the Chilean desert to Hawaii to the South Pole, just released an image depicting the jet in the finest detail ever captured. The image reveals an odd, twisted shape at the base that scientists had not expected. The new finding is detailed in a study, published Tuesday in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

The image reveals the shooting jets of plasma from the proximity of a supermassive black hole in great detail.

The image shows a disc of swirling gas and dust around the black hole, with the jet of plasma shooting out from it in the form of a stream of red.

ODD AND TWISTED

The team behind the image were using the Event Horizon Telescope to observe a quasar, dubbed 3C 279, located 5 billion lightyears away in the constellation Virgo. A quasar is an extremely bright and active galactic nuclei, which contain supermassive black holes at their center.

This particular object was identified as a quasar because of its super bright light that shines in its center, and flickers as material such as gas and stars fall into the black hole. Black holes feed on surrounding material, gobbling them up as they grow in size.

The black hole at the center of 3C 279 was shredding the gas and stars within its vicinity, forming a surrounding accretion disk, and spitting some of the gas out in the form of two jets of plasma at nearly the speed of light.

Capturing the image of the jets in this great detail allowed the scientists to observe their base, and what they found was unexpected.

Scientists believed that the base of the jets would start off in a straight stream like the rest of their body. However, the new image revealed a twisted shape at the base.

“This is like finding a very different shape by opening the smallest Matryoshka doll,” Jae-Young Kim, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany, and lead author of the study, said in a statement. “We knew that every time you open a new window to the Universe you can find something new. Here, where we expected to find the region where the jet forms by going to the sharpest image possible, we find a kind of perpendicular structure.”

The team of researchers behind the new study are not quite sure what causes this kink at the base of the jets, but they believe it may have something to do with how the jets interact with the accretion disk surrounding the black hole.

Aside from a twisted base, the image also creates an optical illusion. One of the jets points directly towards the Earth, and appears to be moving towards us at about 20 times the speed of light.

It appears to be moving at a much faster speed because the material is chasing after the light that it is emitting.

TELESCOPIC ACHIEVEMENTS

Similar to the unveiling of the first ever image of a black hole, this first detailed image of the plasma jets is also a major astronomical feat.

In order to capture the image, telescopes from different parts of the world worked together to essentially act like one very large Earth-sized telescope by collecting the raw data as the Earth rotates. The observations were done in April, 2017.

The raw data was then transformed into a highly detailed image. The resulting resolution was 20 micro-arcseconds, which is equivalent to identifying an orange on Earth as seen by an astronaut from the Moon, according to the researchers.

"The EHT array is always improving," Shep Doeleman founding director of the Event Horizon Telescope and an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astronomy, said in a statement. "These new quasar results demonstrate that the unique EHT capabilities can address a wide range of science questions, which will only grow as we continue to add new telescopes to the array.”

The Event Horizon Telescope observing campaigns take place once a year. However, this year’s campaign was cancelled in response to the coronavirus outbreak. Instead, scientists at the observatory will focus on data that they had gathered the years before.