“Beyond” Artemis 3: NASA’s next lunar lander won’t be made by SpaceX

A new round of proposals will see private companies develop new Moon-landing technology.

As NASA makes its first step toward the Artemis I launch, the agency is already thinking ahead. NASA announced on Wednesday that it would launch a round of proposals for a new lunar lander — one for use past the Artemis III mission, currently targeted for 2025.

“Additional landers will help increase the cadence of the missions at which we help astronauts land on the Moon,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said in a press conference.

The round of proposals will see various private companies submit proposals for both crewed and uncrewed landers, specifically for missions “beyond the third Artemis,” Nelson says. The agency expects to eventually launch about one landing mission to the Moon every year, all with an eventual launch to Mars in “the late 2030s or 2040s.” Because of existing contracts with the Human Landing System, SpaceX proposals will not be considered on this particular proposal.

That could open up the doors for Blue Origin to once again vie for a lunar contract after it lost out last round. Its round of legal challenges with NASA delayed some of the agency’s ambitions to actually get to the Moon for a few months.

Full details have yet to be released, but the agency expects to take input from industry partners early in April before sending out a final request for proposals “later in the spring,” according to Lisa Watson-Morgan, Human Landing System program manager at NASA.

Artemis I has been rolled out to the pad, awaiting an upcoming “wet dress rehearsal.”

What is the Artemis program?

The Artemis program is NASA’s ambitious program that will eventually see humans land on the Moon for the first time since 1972. The program was started in 2017 under President Donald Trump, combining aspects of previous programs under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama that developed the Space Launch System and Orion human capsule. Prior to Artemis, the Bush administration sought a human return to the moon under the Constellation program, while Obama focused on the Asteroid Redirect Mission as the first step toward a trip to Mars.

The Biden administration has kept Artemis largely intact. The initial fleet of missions will see the launch of three missions:

- Artemis I, an uncrewed mission to the Moon as a test for the Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System to work out any technological hiccups along the way. NASA expects to launch the mission later this year, no earlier than June.

- Artemis II, a crewed mission that will see NASA astronauts return to the Moon, but stop short of landing. NASA intends to launch this mission no earlier than May 2024. It won’t orbit the Moon — rather, it will swing around its far side before returning to Earth.

- Artemis III, the final scheduled mission, will see humans set foot on the shadowy South Pole of the Moon. NASA wants a woman and a person of color to be part of this mission, though astronaut selection has yet to be announced. The mission will rendezvous with a space station known as the Lunar Gateway (that has also yet to be launched) before sending a crew of two down to the surface in the Starship HLS vehicle. This makes NASA’s existing partnership with SpaceX critical to the success of the mission.

The new round of proposals sees the agency looking beyond its initial three missions and into a continuous set of lunar missions — something necessary if the agency intends to make good on its plans for a Moonbase.

What about Mars?

A photo of Mars taken by NASA’s Perseverance rover.

Several times throughout the press conference, Nelson, Watson-Morgan, and NASA associate Jim Free, associate administrator for NASA’s Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate, reiterated the agency’s commitment to a Mars landing. Free says everything the agency does with Artemis also has Mars in mind, and Nelson says the lessons learned from Artemis will tell the agency how humans will fair in deep space.

NASA wants to land humans on Mars in the late 2030s or early 2040s, using much of the same architecture as the Artemis program. But rather than a few days flight, a mission to Mars will take six months, during which astronauts will be exposed to the dangers of space radiation and the expedited wear and tear of the human body in a microgravity environment. The Lunar Gateway even ties into this — while the International Space Station orbits a couple hundred miles above Earth, the Gateway will be in deep space, away from the protective shield Earth provides astronauts from the harsher space environment.

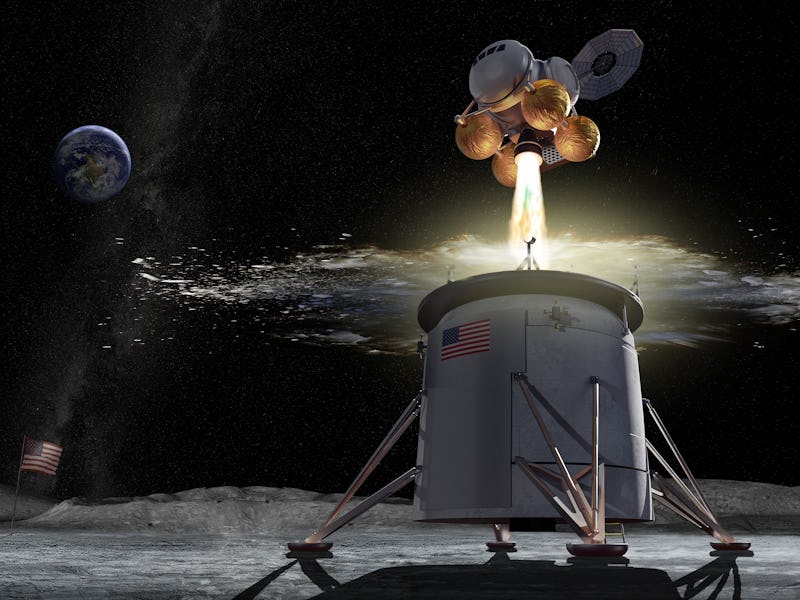

The SpaceX HLS will deliver NASA astronauts to the surface of the Moon for the first time in more than 50 years.

Is SpaceX still involved in Artemis?

During the call, the agency reiterated its support for the existing HLS contract and called for new developments in the existing contract with the extended Artemis missions in mind. The new RFPs will serve as something more of missions to be done in tandem with the HLS or as a backup.

“Competition leads to better, more reliable outcomes,” Nelson said. “It benefits everybody, it benefits NASA, it benefits the American people. It’s obvious, the benefits of competition.” Existing Artemis III plans thus remain in place, but in concert with the RFPs, NASA will work with SpaceX to further develop the sustainable lunar outpost development.

Money for the program — both the new RFPs and NASA’s existing lunar partnership with SpaceX — are expected next week, when President Joe Biden will release the Fiscal Year 2023 budget.

“Artemis is a complex campaign with many exciting milestones ahead of us,” Free says.

This article was originally published on