The scientific reason why Olympians are embracing this new fitness trend

“Literally every single day of the Olympics, I've had calls.”

What do Olympians, Navy SEALs, and many women over the age of 55 all have in common? They’ve embraced a new kind of physical therapy and training method called blood flow restriction (BFR).

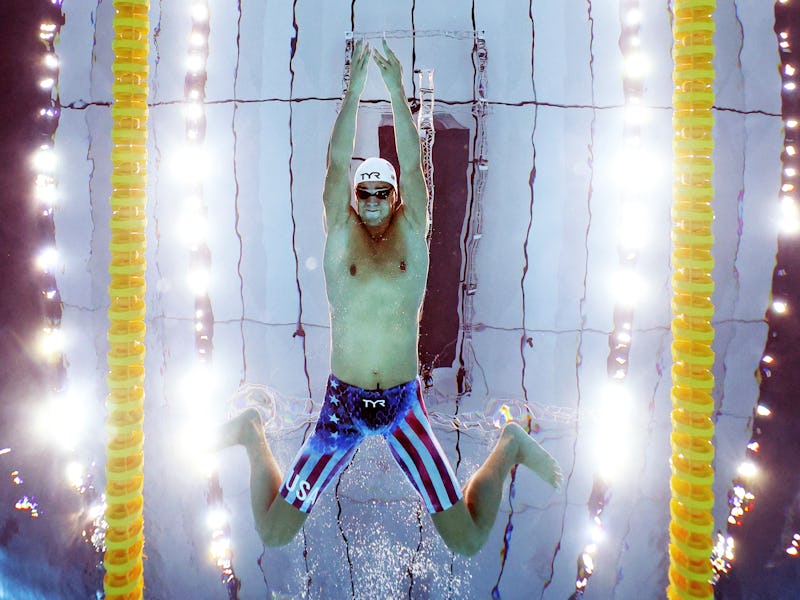

In Tokyo, athletes (and sometimes brand ambassadors) like Michael Andrew and Galen Rupp have been spotted in the tell-tale bands, reducing blood flow in their arms and legs as part of a post-sport recovery.

Steven Munatones is the CEO and co-founder of KAATSU, a company that developed the original BFR method under its inventor, Yoshiaki Sato, and sells specialized equipment for it. An inventor and researcher, Sato developed the method — also referred to as kaatsu — in the 1960s. Munatones, meanwhile, is an International Marathon Swimming Hall of Fame inductee.

“Literally every single day of the Olympics, I've had calls from discus throwers from Australia, rowers in Romania, powerlifters from Poland, you name it,” Munatones tells Inverse.

“These athletes are saying, ‘Hey, you know, I just found out about your product here in the Olympic Village, is there any way I can get my hands on a unit?’”

Turns out, there might be something to it. While a trend to spectators — remember cupping during the 2016 Olympics? — sports medicine doctors have already given their modest approval to the practice as a supplement to strength training and post-operative physical therapy.

Olympian Michael Andrew trains with his KAATSU product on. He’s a brand ambassador for the company.

However, the science remains mixed: For example, in a 2020 study, blood flow restriction is described as an “innovative training method for the development of muscle strength and hypertrophy,” while a 2021 systematic review of the practice argued there was “limited evidence” that it actually improved vascular function in healthy young adults.

Munatones, as well as some professional athletes, give it much more credit, claiming it can help with recovery, rehabilitation, even resetting circadian rhythms.

What is blood flow restriction?

This is how blood flow restriction works: Specialized bands — a little like a blood pressure cuff at the doctors’ office but narrower — are placed around the top of an arm or a leg.

“Suddenly your hand goes from very light pink to rosy pink to a beefy red.”

They are inflated via a small electronic unit to induce light pressure on the muscle. The wearer engages in low-intensity resistance training, like repetitions of a bicep curl, but with less weight than usual. Blood flows to the muscles past the band, and the muscles progressively swell with more blood as their trip back towards the torso slows.

“Suddenly your hand goes from very light pink to rosy pink to a beefy red,” Munatones explains.

“When it gets beefy red, what's actually happening is all the very small capillaries that we don't even think about — that we don't even realize we have — are totally engorged in blood,” he says.

In traditional strength resistance training, stress is put on the muscles by lifting weights or using your own body weight, which essentially leads to small tears in the muscle fibers and eventual repair when you rest. With enough training, muscle fibers grow in size in a process called hypertrophy — something weightlifters are normally seeking.

According to Lance LeClere, an orthopedic doctor with the U.S. Navy who co-authored a 2019 review on BFR, there are two components to the practice: “More muscle fibers are being used during exercise, and they are being signaled to become larger as well,” LeClere told Inverse.

Repetitions for therapy or exercise can be done with “20 to 30 percent of normal maximum effort, which means patients or athletes can get a strenuous workout at much lower levels of weight,” he says.

(The U.S. Military academy has partnered with KAATSU on research projects.)

There’s some promising evidence supporting BFR in certain contexts:

- In 2018, scientists found that older adults doing BFR with low-weight resistance training experienced gains in strength and size in their leg muscles comparable to high-load resistance training after 12 weeks.

- In a 2017 study, knee recovery was more successful after operations in 17 people with BFR than without it, when it was combined with physical therapy — but only with certain exercises.

- In 2002, scientists found rugby players who underwent low-intensity training paired with BFR, compared to those who did not, saw increases in knee extensor muscles.

What does blood flow restriction do?

A 2013 review of BFR published in The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research lists seven potential mechanisms that may stimulate the body’s response to the method.

One theory is that it mimics traditional weight training with much heavier weights. A limb with a BFR band on it may receive the same kind of “stress” under mild resistance training as one without it, lifting heavy weights.

Laura Wilkinson, an Olympic diver, uses BFR. Here she is competing in the 2017 USA Diving Summer National Championships.

Another theory revolves around proteins called insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) found in muscles. Bodies produce this in response to exercise, which can help muscles grow. BFR, some studies suggest, increases circulating IFGs in muscles.

Other chemicals involved in strength training may also be at play: For example, metabolites like lactate build up in the part of the body restricted by the bands. This can later lead to muscle growth.

“When our vascular tissue fills up with blood, we are imitating exercise,” Munatones says.

“We're mimicking a lot of exercise with KAATSU and we're just sitting at our desk or sitting on our couch,” he claims.

LeClere says, “By using lower weight but still building muscle, BFR allows for more aggressive early rehab after surgery.”

Who should use blood flow restriction?

Practitioners of KAATSU, which is headquartered in Huntington Beach, California and distributes products and training in over 49 countries, say it’s not just about lifting weights.

The practice — and certainly, the countless BFR products that have branched out from KAATSU — seems to be most popular with weight-lifters and gym-types. But its initial growth began with research on elderly patients with cardiovascular and orthopedic conditions. Older folks are still a huge portion of KAATSU’s business.

Diver Laura Wilkinson posts about her KAATSU bands.

Munatones says 70 percent of KAATSU’s market is women over 55. His mother, who is 83, and his two sisters use BFR regularly. They “use KAATSU so often, and it's simply because it's so gentle, they can do it while they're reading a book, they can do it while they're walking their dog,” he says.

Sports medicine doctors seem to agree that it can work in both athletes and people with a reduced capacity for exercise, if not as a replacement for exercise altogether.

In an article from a 2017 newsletter of the American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine, LeClere and another doctor, Ashley Anderson, write that with normal resistance training, BFR “could result in increased strength and muscle hypertrophy in healthy athletes,” and that “BFR while exercising at lower intensity could be used with subjects after surgery or in populations unable to perform higher levels of exertion with routine resistance training.”

The method is not without its risks when done overzealously: too much pressure on a muscle, or ischemia, can or cut off blood to the muscles and lead to tissue death.

This is perhaps why Munatones is quick to point out that, when done correctly, the pressure is as gentle as “a really tight T-shirt” and says comparisons to a tourniquet are unfounded.

Why is blood flow restriction popular now?

BFR’s rise to prominence is a long time in the making.

Sato, who invented the BFR or kaatsu method, was inspired to investigate BFR after realizing that the restricted blood flow he felt while kneeling during a Buddhist ceremony resulted in the same sort of swelling experienced after he lifted weights.

For years, he experimented on himself, using bicycle tubes to put pressure on his muscles.

One pulmonary embolism, a miraculous recovery from a ski accident— where Sato describes actually building muscle inside a cast during recovery with BFR — and much trial and error later, led him to a patent. In the early 2000s, Sato collaborated with professors and cardiologists at the University of Tokyo and honed the method in trials with elderly patients.

Also in 2000, Munotones — then a member of the US national swim team — wasn’t making much headway in promoting it to his colleagues.

“I could not convince my coach and my fellow coaches — people that had known me for a long time — I could not convince them to use KAATSU,” he says. “It took me a long time. It took me seven years.”

Now, however, the tide has changed: kaatsu has become KAATSU, a brand. Munotones credits mostly word-of-mouth marketing. There are even competitors who branched off after training with the company.

“At first, to be honest, I was rather pissed off. I spent all this time to educate people and pay them, and then they go off and copy it,” he says.

But then he started getting more phone calls. “I realized,” Munotones says. “‘oh, I would much rather be part of a growing market.’”