Chloroquine: The strange story behind the "cure" for COVID-19 that's going viral

"People are looking for quick solutions of course and this bubbled to the top."

We know how to slow the spread of COVID-19 (social distancing, hand washing, etc). But as more people become infected, scientists are moving quickly in search of a cure.

But the internet is moving faster.

Update, April 7 — On Tuesday, March 17, a small, preliminary study on the anti-malarial drug chloroquine (pronounced klaw· ruh·kwn) as a treatment for COVID-19 published in a peer-review journal online. While the findings appear tentatively promising, the society that publishes the journal issued on April 3 a statement expressing their grave concerns about the paper's standards and methods, calling its findings into question.

The internet does not wait for peer review and scientific debate, however. As soon as it published, the study blew up into something far bigger, thanks to the power of Elon Musk's 32 million followers on Twitter and a Google doc.

Here's the story of how chloroquine went from anonymity to a proposed cure for a pandemic, in a matter of days.

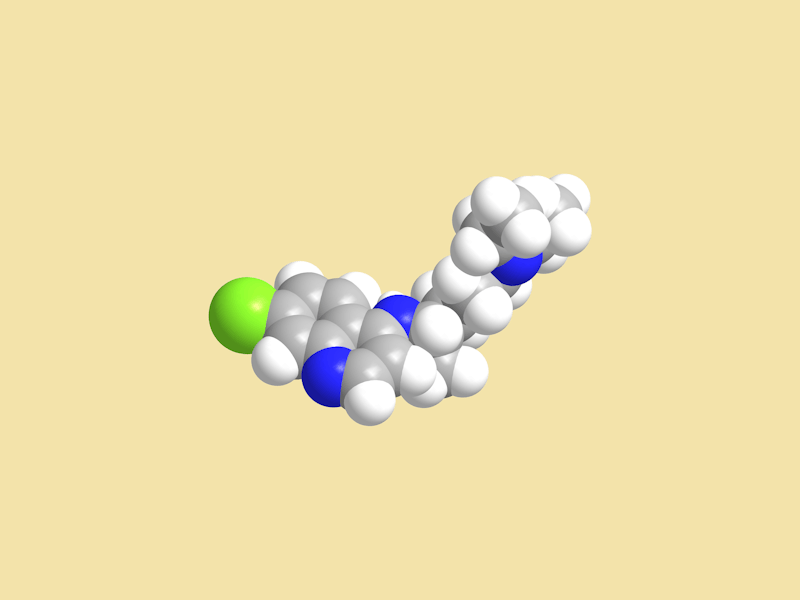

At the time of writing, the global case count for COVID-19 surpassed 211,000, there is ongoing research on drugs like Remdesivir, which was used to treat Ebola. Chloroquine is an anti-malarial drug that has treated and prevented malaria since the 1940s. It is the subject of at least three clinical trials registered with the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

It is important to note: chloroquine does hold promise as a treatment for COVID-19. A paper published on Monday, March 16, in the journal Bioscience Trends, suggests that chloroquine is a "breakthrough treatment" for Chinese patients. The drug has since been added to treatment guidelines in South Korea, Belgium, and China. However, Belgium's guidelines stipulate chloroquine should only be used in hospitalized patients, and the "results of ongoing clinical trials are eagerly awaited, ie., the evidence is still preliminary.

On Thursday, March 19, Trump suggested during a White House press conference that the Food and Drug Administration, which has not previously recognized any drug as a treatment for COVID-19, had approved the use of chloroquine to treat COVID-19.

"They've gone through the approval process. It has been approved. They [the FDA] took it down from many many months to immediate," Trump said. "We're going to be able to make that drug available by prescription."

As chloroquine is already FDA-approved for the treatment of malaria, it does not have to undergo the traditional rounds of safety testing that a new drug would have to, before it could be put to market.

Inverse has contacted the FDA seeking confirmation that the agency is now approving the use of the drug as a treatment for COVID-19.

But at the time of writing, Bloomberg news has reported that the FDA has not officially approved the use of the drug for COVID-19.

The confusion is symptomatic of the drug's incredibly rapid rise from obscurity to national news.

In the past week, Cholorquine has gone from anonymity to the forefront of medical conversation using channels outside of academia and drug development.

On Monday, Musk tweeted a link to a google document titled "an effective treatment for Coronavirus."

"Maybe worth considering chloroquine for C19," the billionaire founder of Tesla, SpaceX and the Boring Company commented.

But the subject of Musk's tweet is not a scientific paper, rather a Google document that has since spawned a new conversation around the drug's efficacy for COVID-19 treatment.

The Google document is not peer-reviewed, but it cites several peer-reviewed studies, as well as phone calls and email conversations with scientists. Despite zero evidence, it has has been reported on by other news outlets like Fox News and the English-language French news website, The Connexion, as if it is a scientific study.

This is just not the case. Still, it served as the opening act for a far larger conversation that has unfolded this week.

Gregory Rigano is a co-author of the Google document. Rigano is not a scientist. He's a lawyer who has spoken about chloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment three times on Fox News this week.

Rigano tells Inverse he has been organizing scientists across the biopharmaceutical world for over a decade. He makes big claims — including that chloroquine and the antibiotic azithromycin (used to treat infections like pink eye) are "cures" for COVID-19. He also says he is working with scientist Didier Raoult, the director of the Mediterranean Institute of Infection, on a chloroquine-based treatment. Inverse contacted Raoult for comment multiple times, but he did not respond to repeated requests.

Rigano was reluctant to take full credit for the findings touted in the document.

"I need to let [Raoult] have his day here," Rigano tells Inverse. "It’s the first well-controlled study showing that hydroxy chloroquine and azithryomycin are cures to coronavirus."

"Him and his team are saving us," Rigano says.

Raoult is reported as the lead author of a study that claims to be published in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents as of Tuesday, March 17. As of the time of writing, the cited link to the study returns no results, but Raoult's institution has released a manuscript of the paper on their website.

Hartmut Derendorf, a professor emeritus of pharmaceutics at the University of Floria is an editor of The International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. He confirmed to Inverse that the study has been peer-reviewed and submitted to that journal:

"The paper will be published shortly and is currently being processed," Derendorf says.

The study was conducted on 36 participants with confirmed COVID-19 infections. It found that all six patients taking hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin tested negative for COVID-19 after 6 days of treatment. A further 14 patients took only hydroxychloroquine, and 8 of them tested negative after the study period. In the control group, 2 patients tested negative at the close of the study.

But the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, which publishes the journal, has since questioned the rigor of the that peer-review process.

The group's statement, released April 3, notes that "the article does not meet the society's expected standard." It also mentions that there wasn't adequate explanation for why some patients were included in the study at all, and questions whether steps were taken to ensure patient safety. The concerns put the study's findings into doubt, and reinforce that further work is needed to determine the drug's effectiveness for Covid-19.

The doi listing for Raoult's paper is not functional, as of publishing. The paper however, was accepted to the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents.

The study was conducted on 36 participants with confirmed COVID-19 infections. It found that all six patients taking hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin tested negative for COVID-19 after 6 days of treatment. A further 14 patients took only hydroxychloroquine, and 8 of them tested negative after the study period. In the control group, 2 patients tested negative at the close of the study.

Importantly, Trump did not discuss the use of azithromycin when he endorsed the use of chloroquine during the press conference on Thursday.

"For ethical reasons and because our first results are so significant and evident we decide to share our findings with the medical community," the authors write.

"Him and his team are saving us."

Mattias Gotte is chair of the University of Alberta's Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology (he is also researching Remdesivir). He tells Inverse that the paper's findings are interesting.

"I do think that the results are potentially interesting, and warrant further investigation with respect to both efficacy and underlying mechanism of these drugs as potential COVID-19 treatment," he says.

"The authors pointed out that this study is preliminary in nature and there are limitations."

The budding research on chloroquine suggests that it may be time to take it seriously. But the way that research has gained mass attention is unorthodox, to say the least, and moving at lightning speed.

Gregory Poland is a professor of medicine and infectious diseases at the Mayo Clinic. He's the director of the Mayo Clinic's Vaccine research group.

"I would urge us to take these with a grain of salt."

"I would urge us to take these with a grain of salt," he tells Inverse regarding the hype around chloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19. "Until randomized clinical trials are published we can't tell if it's anecdote. Is it due to some unforeseen or improbable set of circumstances?"

"The medical literature is littered with tens of thousands of case reports like this where there is a claim of efficacy only to fall apart when randomized clinical trials are done."

When Inverse asked him why chloroquine seems to have experienced such a meteoric rise to the forefront, he offered a simple response.

"I think, panic," he says.

The Elon tweet and the Google doc

Musk's tweet referencing the Google doc generated over 1 million impressions, Rigano says. It's been liked nearly 50,000 times. But the Google document is far below the standards of a scientific journal paper, even if the results of Raoult's subsequent study do seem promising.

When the document was first released on Friday, March 13, there were three co-authors on the document, including Thomas Broker, a professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics at the University of Alabama. Broker's name has since been removed.

He calls the Google document "a pastiche of previous published research articles and recent news reports." He also tells Inverse that his name had been "gratuitously attached" to the document.

"I asked the actual authors to remove my name."

"I asked the actual authors to remove my name. I am glad that they did," he says.

"I neither contributed to, wrote any part of, nor had advance knowledge of this google.com document. I have never conducted research on RNA virus pathogens," Broker confirms.

The Google doc also cites a 2005 study on primate cells, showing that chloroquine may slow the spread of SARS coronavirus, at least in cell culture. When Inverse reached out to the researchers behind that study, they directed the inquiry to a CDC spokesperson.

"CDC is aware of reports of various medications being administered for either treatment or prophylaxis for COVID-19, including those demonstrating in vitro activity against SARS-CoV-2," CDC spokesperson Kristen Nordlund tells Inverse.

"At this time, it is important to ensure robust clinical data, gathered from clinical trials, are obtained quickly in order to make informed clinical decisions regarding the management of patients with COVID-19."

In essence, the Google document doesn't present any new information. Instead, it highlights the fact that chloroquine has been used in other countries as a possible COVID-19 treatment, and has a history as an anti-viral.

That said, the document has generated a great deal of coverage on its own, and perhaps raised the profile of Raoult's legitimate research.

After the study was released on Wednesday, Rigano appeared again on Fox News. Speaking to Tucker Carlson, he said that the study reports a "100 percent cure rate" for coronavirus. That 100 percent cure rate refers to the six patients who received both hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in Raoult's study.

"What we're here to announce is the second cure to a virus of all time," said Rigano.

He also plugged his Twitter account and argued that this should be disseminated to the scientific community immediately.

Carlson, for his part, appears stunned on the newscast. "So, I only know what you're telling me," Carlson says. "I do know that it's very unusual of a study of anything to produce results of 100 percent."

There is some evidence that hospitals are starting to use hydroxychloroquine in their treatment regimens. On Twitter, Arun Sridhar a Cardiac Electrophysiologist at the University of Washington, tweeted out treatment guidelines that include the use of the drug.

Rigano, appearing on Fox Business also stated that hospitals "around the country" are using chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine to treat their patients.

Rigano is effectively working as a spokesperson for Raoult's work. And that study has also served as a launchpad for Rigano's new project, which plans to operate outside of the traditional clinical trial framework.

"People are looking for quick solutions of course and this bubbled to the top."

Rigano claims to be the co-leader of a "decentralized organization" of scientists who are looking into the effects of chloroquine on COVID-19.

"We’ve been in contact with each other for years, exchanging different research operations. We decided to come together to solve this issue collectively. We are in touch with doctors and pharmaceutical manufacturers across the world," he says.

Rigano is attempting to start an "open data clinical trial" for COVID-19 prevention. Raoult is listed a "leading scientist and physician" on the project's website. The Google doc is referred to as a "draft paper" on that website. The trial is intended to enroll medical doctors, and "front-line healthcare workers" who would take the drug themselves.

"Unlike a typical commercial drug trial, our objective is to share trial data with the public* and health-care professionals as close to real-time as possible (with a reasonable level of data quality assurance)," the website reads. [Emphasis theirs]

"We cannot wait for the government or a publicly traded corporation to go through the traditional route of a clinical trial. It will take too long and the disease will spread immediately," Rigano argues.

"It would be outside the norm for medicine as we know it..."

Qualms about speed aside, accuracy is also important. That's the reason the randomized, controlled clinical trial is the gold standard for drug development, Gotte says. The new study makes a compelling case for scientists to look into chloroquine, but it isn't a justification for an overhaul of drug development.

"Randomized controlled clinical trials are the gold standard to evaluate investigational drugs," he says. "Other clinical data could be of potential interest, but randomized clinical trials are required to evaluate treatments."

Poland agrees. He acknowledges that people are desperate for a solution, which means that "under protocol" we should investigate things that hold promise, like chloroquine. But we just don't know for sure if something is really a treatment until you do clinical trials.

As for Rigano's proposed experiment, he says that it is not the same as a traditional clinical trial. The protocols are there to ensure both safety and efficacy.

"It would be outside the norm for medicine as we know it to just assume that they're beneficial and not harmful, and that it would benefit in the specific case of COVID-19."

What's next for Chloroquine?

At the end of the day, chloroquine has potential, says Vincent Racaniello, a virologist at Columbia University. He tells Inverse that chloroquine can clearly stop COVID-19 from replicating in cell culture. How the translates to human bodies is a different matter, however.

"The mechanisms, studied with other viruses, are known. However it needs to be tested in people," he says.

"As it is a licensed drug for malaria it can be used in people in clinical trials to test its effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 [that's the official name for COVID-19 used by virologists]."

"People are looking for quick solutions of course and this bubbled to the top."

When Inverse sent the study to Racaniello, he noted that the methods are solid and in line with what you might expect in the field. But he adds that chloroquine can have many side effects. And though these authors don't report any side effects from the use of azithromycin and chloroquine, this single, small, and preliminary study isn't enough to suggest we should be using the drugs to treat all or even some COVID-19 cases.

"The paper does not report adverse effects of using both drugs together, but the number of patients is small. In larger numbers this could change," Racaniello says.

With weeks (or months) of social distancing ahead of us, we are looking for answers fast. Chloroquine may provide one. But one study tweeted by a celebrity and the President's erstwhile enthusiasm won't make or break it. Rather, this is only the beginning.

Correction: A previous version of this story misidentified the class of the drug Chloroquine. It is an anti-malarial drug.

Update 4/7/20 9:34 a.m.: This story has been updated to include the International Society of Microbial Chemotherapy's April 3, 2020 statement of concern regarding Raoult's study on chloroquine and azithromycin.

This article was originally published on