Legend of Zelda Game & Watch reveals Nintendo's most powerful weapon

I didn’t need it. But I couldn’t help myself.

I picked up my kid at pre-school and drove to Target. We walked toward the electronics section, my little dude excitedly pointing to the giant paper Christmas ornaments. I didn’t see what I was looking for, so I asked a red-vested worker shelving accessories.

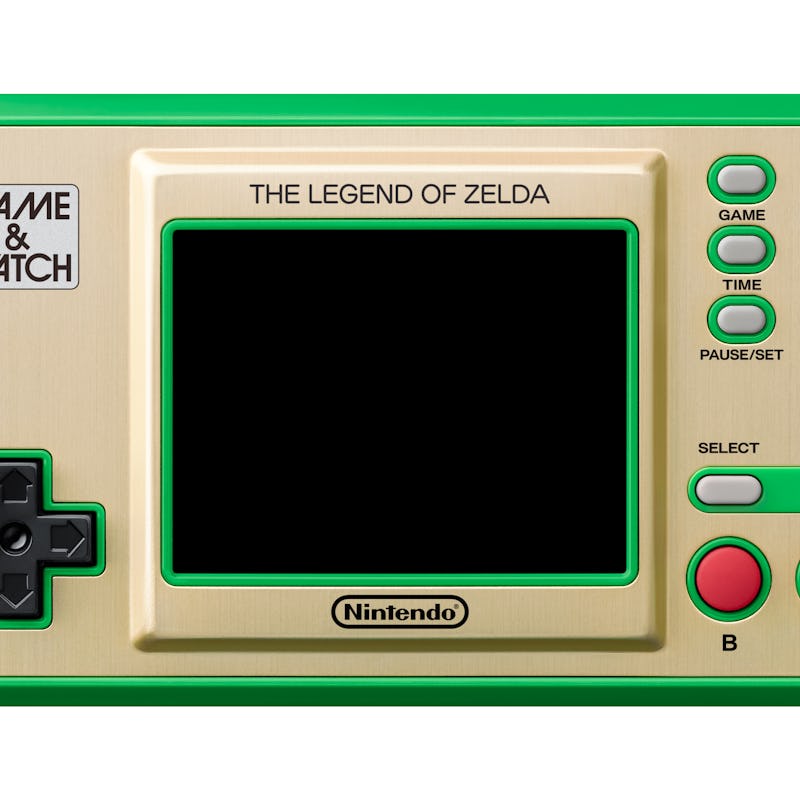

“I know where one is,” she said. Moments later, she returned with it: Nintendo’s new Game & Watch: The Legend of Zelda edition.

“New” is a bit of a misnomer. Technically it’s a new product, but the underlying technology and form factor are over 40 years old. The Game & Watch, first released in 1980, was Nintendo’s precursor to the Game Boy. Each device was a self-contained unit with a single game. But once the Game Boy and its swappable cartridges launched, the G&W line was fully relegated to “novelty” status, making periodic returns in collections, downloadable one-offs, or as frequent buyer reward freebies.

In 2020, Nintendo blew the dust off the old molds and manufactured a special Super Mario Bros. 35th anniversary edition. This year, it repeated the trick with Zelda, Link, and Ganondorf, selling a Game & Watch that plays the original Legend of Zelda, its sequel Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, and the Game Boy classic The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening. And like it’s done many times, Nintendo successfully convinces millions of people to buy something they don’t need — and those fans are utterly delighted to do it.

“I love this thing,” tweeted out GamingBible’s Head of Content Mike Diver, sharing pictures of his new device that plays three games he undoubtedly already owns in several formats.

“If I’m making fun of anyone, it’s myself.”

He’s not alone in his enthusiasm for the darling pocket-sized toy; all release day my Twitter feed was lined with people’s photos of the thing: on their desks, in their hands, turned around to show off the rear-side Triforce that glows. For $49.99 (the same price as a year of Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack), you, too, can buy both a “Game” and a “Watch” that, let’s be honest, will likely return to its shelf after a ten-minute session on Day One. And in our modern age of cynicism and myopic anger, I have not yet heard one complaint.

If I’m making fun of anyone, it’s myself and my ilk. And we are legion.

Do not be fooled, Nintendo’s decision to repackage and repurpose 1980s tech to the exuberant hordes is more marketing savvy than “withered technology” innovation. Sony employed a similar scheme, selling a commemorative 40th Anniversary Walkman in 2019. But that device was an MP3 player in a tape player’s clothing. This was no throwback, but a modern gadget with a cheeky screensaver. It also cost 440 Euros and was only available in Europe and Australia.

Nintendo’s Game & Watch basically works the same whether you play it in 2021 or 1981. (To be fair, the originals relied on LCD screens, same as calculators, for their clever animation; the new versions sport crisp color displays, so there’s been an upgrade or two.) The Legend of Zelda edition even comes with Vermin, an original G&W game that appears too easy until the little Octorok-styled moles emerge from the ground with increasing speed.

Vermin is a lot tougher than it looks.

When Vermin was first released in Japan in 1980, it cost 6000 yen, or approximately $60. Nintendo’s Mario and Zelda Game & Watches are similarly priced at $49.99. These are not “collectibles” released to a ravenous crowd eager to spend top dollar for something to be encased in glass. These are, essentially, the same product for the same audience as forty years ago: an affordable toy sold to children (or their parents) who want to play a fun little game.

The object itself is a tiny little miracle of restraint. In 2021, you could stuff some serious horsepower even into something as small as a Game & Watch. But the point is to deliver a single experience in the palm of your hand. (Okay, two experiences; you can also see the time or set a timer in an interactive clock-version of Hyrule. Surely these should have always been called Game & Clock?)

The first time I took it out of the package, I was surprised at how vibrant the unit itself looked. The screen and buttons are a Hyrulian green that makes every pushable or viewable surface pop. The face of the device is coated in something that looks like brushed metal, with the “Game & Watch” logo embedded in its own silver tile. The design and manufacturing polish are spot-on and provide a spark of recognition to those who were around for the G&W’s heyday. That’s what Nintendo is selling with these retro devices — memories made tangible at mass-market prices.

That same authenticity is why so many forked over the same fifty dollars to hold a Nintendo 64 controller or Sega Genesis controller in their hands again (or both). You can buy cheaper controllers with modern features to use with old games. But nostalgia is a strange and powerful thing. It’s always in high demand, and the only supply chain issue is within our weakening neocortex.

Nintendo has something its gaming competitors do not: a long history. The company’s success in a turbulent and unpredictable industry is in part due to its remarkable ability to tap into players’ memories in a way that feels intimate and personal. This is not a new phenomenon. (To list even a smattering of Nintendo’s attempts to mine its past would take up more words than my editor afforded.)

In the intervening years, Nintendo has experimented with how to sell its old games. The Wii, Wii U, and 3DS offered robust virtual consoles with individual downloadable titles. Then came the NES and SNES Classics, miniature plug-and-play boxes with a couple dozen titles. The latest strategy is tying back catalog titles to its Nintendo Switch Online service, a practice unpopular with a vocal minority but good enough for 32 million subscribers.

But whereas previous anniversary releases would often be ROMS printed to a disc (as was the case with both The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time’s re-release on GameCube and Super Mario All-Stars’ ignoble fate on Wii), now Nintendo is aiming to take its classic franchises beyond your television — to your LEGO box, your local movie theater, and indeed, in your hands.

I’ve never beaten Zelda II or Link’s Awakening. But I might now, if only because it’s so easy to pop this new Game & Watch in my back pocket and power it up at a moment’s notice. Though these games are over three decades old, to have them wrapped in such a slim, light form factor still feels oddly magical.

At a time when our phones can do everything a gigantic room-sized computer would have done decades ago, it takes a lot to be impressed by technology. So when the creative minds at Nintendo go the other way, as is their nature, they impress you with a feeling.

It’s the little glint of surprise when you turn the device around to see the glowing Triforce on the back panel. Or the inescapable delight of hearing that tell-tale chime emit from its tiny speakers the first time you turn the device on, like discovering a secret hidden decades before.

Sure, there are other, better ways of playing these games. But you’re not buying this to play the opaque, divisive sequel with its side-scrolling swordplay and maddening random battles. You’re buying this to play Zelda II on a portable the size of a business card. Or just to slot the beautiful thing into its included cardboard display case and set it, happily, on your desk.

Cult of Nintendo is an Inverse series focusing on the weird, wild, and wonderful conversations surrounding the most venerable company in video games.

This article was originally published on