Michael Crichton’s Pulpiest Thriller Set the Stage for Jurassic Park

Crichton’s infamous grudge against novelty theme parks began back in 1973.

Michael Crichton became famous for writing novels drenched in charts, science, and insights on our relationship with technology. But he wasn’t afraid to get pulpy — most of his early novels were potboilers drenched in tawdry sex and cheap drama. These stories of gangsters and smugglers contain traces of his later skill and style but, in his own words, they were disposable.

The Andromeda Strain, Crichton’s 1969 bestseller about humanity battling a terrifying microorganism, changed his fortunes. Using his medical training as inspiration, Crichton established himself as a fresh voice in popular sci-fi, and with some screenwriting experience and a desire to direct thrown in, he found himself writing and helming Westworld

Set in a theme park populated by robots almost indistinguishable from humans, Westworld is a bridge between Crichton’s old pulp impulses and the thoughtful sci-fi of Jurassic Park. The latter would make him a superstar, but in the early ’70s, all Crichton had was a $1.2 million budget, a television movie under his belt, and the question of what would happen if robots went haywire.

For $1,000 a day, tourists can visit Roman World, Medieval World, or Western World, which blend historical realism with pop culture stereotypes. While returnee guest John (James Brolin) explains to his newcomer friend Peter (Richard Benjamin) that their western hotel rooms are authentically decorated, they’re not spending all that money to enjoy the ambiance. Their first priorities are to drink whisky, gun down a robot gunslinger (Yul Brynner), and bed mechanical prostitutes. Robots exist to serve every urge, and guests are encouraged to indulge liberally.

You can probably guess that things go wrong, but you probably can’t guess how long it takes; the placid robots don’t go rogue until the 88-minute movie is almost an hour old. Westworld’s age is further revealed by the control room’s preponderance of magnetic tapes, and with the concept of a computer virus not having entered the popular lexicon, technicians speculate the robots are troubled by an “infectious machine disease.” When they finally go haywire it’s kind of just because the script said it’s time, one of the film’s many contrivances.

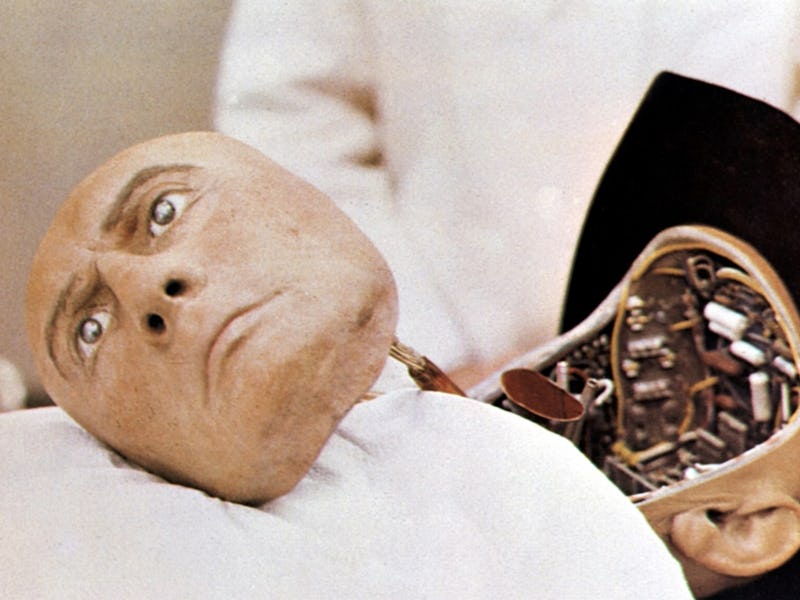

You can’t walk around like this at Knott's Berry Farm.

The glacial pace and dated terminology don’t make Westworld the most thrilling watch, but it remains an intriguing one. The robots’ stilted movements and dead eyes are unsettling, as is how quickly Peter goes from feeling ridiculous in his new duds to wholeheartedly embracing gunplay and sex. The world’s most advanced technology is being used to sate violent horndogs: Peter and John are likable enough, but it’s not a stretch to imagine the park as a paradise for sociopaths.

We don’t really get to know our heroes, which makes Yul Brynner the standout here. His gunslinging robot is programmed to pick fights with guests, and though he dutifully loses duels with Peter, you know trouble is coming. A deliberate inversion of the heroic wanderer Brynner played in The Magnificent Seven, his eventual rampage and Peter’s struggle to survive as a feeble human remains the film’s highlight. It feels like a taste of ’70s future shock, as the thrills of the old West give way to the concerns of science fiction.

Brynner, who took the role out of financial desperation, is chilling as a calm, implacable stalker. He’s a clear precursor to Michael Meyers and the Terminator, and their charming simplicity as villains. There’s no tortured tale about robots gaining sentience and plotting to overthrow us. He wasn’t secretly reprogrammed by terrorists or freedom fighters. An arrogant technology company made a dangerous product they didn’t fully understand, and then it broke. The tech may be dated, but the warning is timeless.

Even acid to the face is barely a deterrent to Brynner’s relentless stalker.

Speaking of dated technology, Westworld was the first Hollywood feature to use computer-processed imagery, as 151 seconds are shown through the gunslinger’s robotic eyes. This was such a cutting-edge idea that Crichton initially thought he’d need the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to help, and while animator John Whitney, Jr. eventually handled the job, he needed four months and the most powerful mainframe computers available to complete a pixelated effect that can now be rendered in moments by free websites. It’s a quaint landmark, as Brynner’s supposedly relentless killing machine appears to have less computing power than a modern fridge, but there’s still a thrill in seeing the switch to Brynner-vision and witnessing the ur-effect that led to today’s Marvel and Avatar movies.

Westworld, like Crichton’s early novels, is fun but disposable, and it’s somewhat baffling that it spawned a television drama infamous for a tedious, overcomplicated mystery box plot. It’s even more surprising there’s never been a theatrical remake, although there was an effort to put Schwarzenegger at the forefront of one in the early 2000s. A lot could be done with modern special effects and its simple premise, especially in a cinematic landscape begging for simple, self-contained thrillers free of endless lore drips.

Crichton would go on to far greater accomplishments, but there are hints of Jurassic Park all over Westworld’s big premise, grand reveal, and hubristic collapse. It doesn’t still wow like Spielberg’s film; it’s too slow, and a little too silly, and Crichton’s direction never rises above workmanlike. But when the gunslinger finally starts his hunt, you’ll understand how the future he once envisioned looked terrifying.