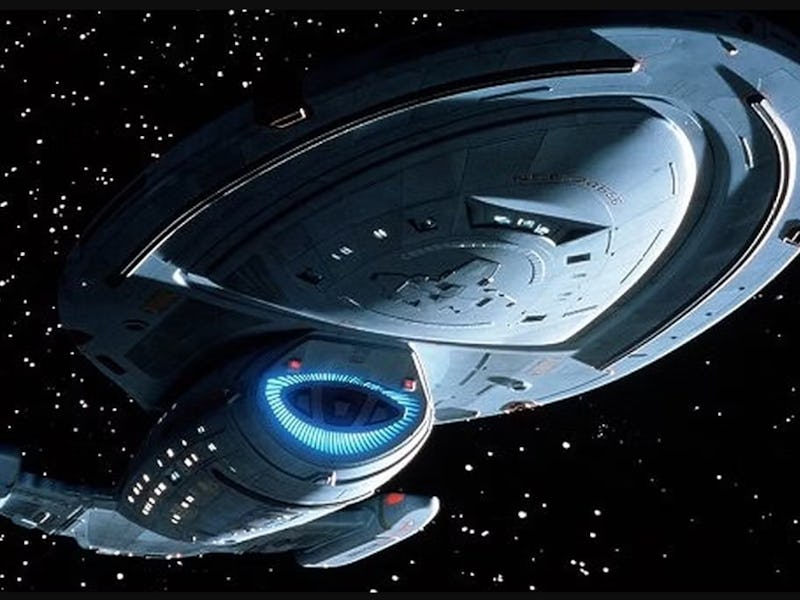

Star Trek: Voyager Remains A Monument To Wasted Potential

The mediocre voyage home.

When veteran Star Trek writer Ronald D. Moore joined Voyager’s writers’ room in Season 6, he was struck by how directionless it felt. The stressed and detached staff seemed interested only in getting the next episode out the door, with little thought to what it meant for long-term storylines and character development. Serialization wasn’t common in late ‘90s and early ‘00s genre television, but Voyager seemed almost aggressively disinterested in challenging itself, and the result was a competent but soulless product that left the entire franchise feeling like it was on autopilot.

Those problems weren’t present when Voyager aired its debut episode, “Caretaker,” 30 years ago today. It’s a strong premiere that briskly sets up a unique premise; unfortunately, the show soon began running away from it.

Voyager’s initial cast.

For the USS Voyager’s inaugural mission, Captain Kathryn Janeway (Kate Mulgrew) is tasked with hunting down a Maquis vessel. The Maquis, for those who don’t speak fluent Trek, are rebels who object to the Federation’s definition of utopia, but in “Caretaker,” both crews soon find themselves with far bigger problems. Their ships are caught in a technobabble plot point that flings them 70,000 light-years across the galaxy, and not everyone survives the journey.

To make matters worse, they’re trapped in the machinations of the powerful and enigmatic alien who nabbed them. An uneasy mutual investigation leads the crews to discover that the alien and his high-tech space station are caring for a coddled species called the Ocampa, but he’s about to breathe his last, and a violent race called the Kazon is threatening to seize his station and enslave his people. Despite the station offering their only apparent way home, Janeway does what any good Starfleet officer would do and orders its destruction, sparing the Ocampa from the Kazon’s degradations but dooming the Starfleet and Maquis crews to a 75-year journey back to Earth.

“Caretaker” was critically acclaimed, and it still deserves the bulk of that praise for being a fun, efficient introduction to Voyager’s stakes and heroes. Most notably, Janeway is established as an empathetic but steely leader, Tom Paris (Robert Duncan McNeill) gets a compelling introduction as a self-serving but secretly good-hearted mercenary who’s a pariah to both the Federation and the Maquis, and Neelix (Ethan Phillips), a bumbling but clever scrap merchant, makes it clear just how far from home Voyager and its crew are. It all feels like a fresh twist to the Trek formula.

Behold the true form of the Caretaker, in all his mid-’90s glory.

Unfortunately, time has also made “Caretaker’s” warning signs flash all the brighter. Janeway’s decision to separate her crew from their loved ones feels rushed and perfunctory. Chakotay (Robert Beltran), the Maquis leader and a supposed firebrand, raises no objections, then immediately agrees to merge their crews, like he knows the plot demands it of him. By the time the episode ends and they set out into the unknown, he already looks comfortable in a Starfleet uniform.

In isolation, these are promises, not flaws. Will anyone resent Janeway for her difficult decision? Will the Federation and Maquis crewmembers — two groups with diametric philosophies — manage to work together? How will a lone ship survive without any support from Starfleet? Fans were presumably looking forward to finding out.

But such questions would be addressed only sporadically throughout Voyager’s opening episodes, then largely ignored throughout the rest of its run. Chakotay soon became indistinguishable from the Federation mold he rejected, Paris had his edges sanded off, and everyone else on the supposedly squabbling crews apparently got together and sang “Kumbaya” off-screen.

Voyager isn’t a bad show — pick a random episode and you’ll probably encounter a decent sci-fi yarn — but it is a show that rejected its own premise. Moore observed that a ship and crew cut off from their society offers a lot of storytelling potential — would they develop their own traditions? How would they contend with dwindling supplies? Could they maintain a sense of discipline and meaning? Voyager didn’t have to ask those specific questions, but it was disappointing that it decided to not ask any at all. By the time Season 2 episodes introduced Amelia Earhart and turned Paris and Janeway into lizards, it felt like it had tossed its potential out the airlock to become an unremarkable adventure-of-the-week factory.

Voyager would eventually introduce Jeri Ryan as Seven of Nine, who’s since become a Trek mainstay allowed to dress properly.

Ratings slipped accordingly. Voyager was never unpopular, and it aired on the relatively niche UPN, but it still seemed clear that the magic and inventiveness of the ‘90s Trek boom was fading. After Voyager ended, Nemesis underperformed at the box office and Enterprise struggled through four shaky seasons before being canceled, and an 18-year run of Trek on television came to an anticlimactic end.

By the time 2017’s Discovery brought the franchise back to the small screen, genre TV had embraced the serialized storytelling Voyager shied away from. One of many contributors to that pivot was the success of Battlestar Galactica, created by Moore in the wake of his frustrations with Voyager. Moore and his creation are hardly infallible, but it’s hard to deny that Battlestar and its storytelling strategy have left the larger legacy.

All of this leaves Voyager as Star Trek’s most shrug-worthy installment, an awkward middle child stuck between the venerable Next Generation and modern Trek’s streaming empire. It can still be fun to revisit. But 30 years on, as Star Trek is again wrapping up many of its TV shows and facing questions about how to stay fresh, you can’t help but see it as a cautionary tale. Just because your characters are searching for safe harbor, that doesn’t mean you should retreat there too.