One of the Most Faithful Comic Book Adaptations Ever Brought Pulp Back to the Big Screen

Welcome to Sin City.

In 2005, three years before Iron Man was launched into the stratosphere and kicked off the juggernaut we now know as the Marvel Cinematic Universe, one of the most faithful comic book adaptations ever made stylishly hit the screens — and became an instant classic.

It’s also an early aughts time capsule, for better and for worse, with producers Bob and Harvey Weinstein to prove the latter. Directors Frank Miller and Robert Rodriguez, as well as guest director Quentin Tarantino, who helms the movie’s opening sequence, have also all had their own share of controversies since, to put it in the gentlest way possible.

So it’s certainly harder to do what is required for nearly anyone who decides to give the pulpy neo-noir a watch: turn off some of that critical thinking. True to the 2000s from whence it sprung, in Sin City, torture is considered a viable way to collect reliable information, heroes survive stunts that include jumps from soaring heights, massive explosions, and even if a woman isn’t a stripper or a prostitute, there’s still gonna be a shot of her in lingerie at the very least, along with some gratuitous violence.

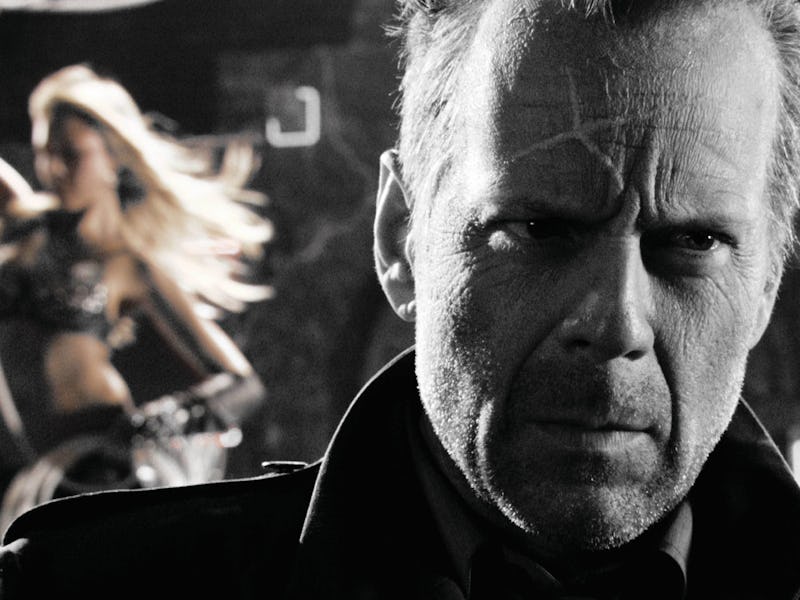

But there’s also a sprawling ensemble cast to bring these interconnected crime tales (which double as blood-soaked love stories) to grimly glorious life. Each is instantly recognizable as they’re introduced via their graphic novel counterparts, and readers of the source material will no doubt note several shots that are exact recreations of the original panels.

As the nonlinear narrative proceeds, with a few colorized elements thrown in for good measure, some of the casting choices allow its various celebrity talent to deviate from, or play with, the image that the industry and audiences had of them at the time. For Alexis Bledel, it’s a way of channeling her role as the naively bookish Rory Gilmore into a deceptively wide-eyed sex worker. As for Elijah Wood, he was clearly determined to leave the innocently vulnerable Frodo Baggins behind by giving a genuinely creepy turn as a cannibalistic serial killer. In the case of Mickey Rourke, it was a chance to resuscitate his career as the grizzled, unstable Marv. And if you really squint, you just might recognize Nick Offerman as the incompetent henchman Shlubb. If others are more heartrending, it’s by circumstance, as is the case with the monumental talents of Brittany Murphy and Michael Clarke Duncan, who have since passed.

Yet for all the fantastic performances on display (along with mostly female flesh), the most essential ingredient Sin City possesses is its willingness to go all in — a quality its sequel lacked. Like many a noir, its (male) heroes are searching for connection and meaning in a society they feel has spat them out, leaving them isolated and disillusioned. If this weren’t obvious, Clive Owen’s Dwight laments the state of things by musing, “There’s no place in this world for our kind of fire,” as he and Rosario Dawson triumphantly gun down their foes. It’s how Dwight sees violent ex-con Marv (Mickey Rourke), who has his own quest to avenge the murder of the mysterious beauty (Jaime King) he spent the night with, musing that Marv would be better suited for a time when he could unleash his natural tendencies in a gladiator arena.

Sin City allowed its sprawling cast to break out of whatever niches they’d been trapped in.

You get the idea. Meaning comes in the form of gleefully unrealistic violence, of rescuing and avenging the women caught up in it — if they’re the right kind of victim, of course. If Sin City had shown any kind of unwillingness to endorse this perspective, it would’ve been as adrift as its follow-up, the 2014 critical and commercial flop Sin City: A Dame to Kill For, which even failed to do justice to the femme fatale its predecessor lacks. It’s likely a very good thing that the formula was never quite right again, with Frank Miller’s attempt to replicate his success in the 2008 movie The Spirit failing so spectacularly that Roger Ebert opined, “To call the characters cardboard is to insult a useful packing material.”

The true spiritual successor to Sin City is likely Zack Snyder’s action-heavy racist fantasia, 300, which takes Sin City’s queasy values to fascist extremes. If ignorance is bliss, then comparison may be a saving grace: With such peers, the politics of Sin City, which at least sympathizes with those it objectifies and indicts wealthy criminals and enablers that include crime bosses, priests, and senators, are a lot easier to swallow.

The movie’s legacy remains complicated of course, and to some, rightfully unpalatable. But a little sympathy for the underdog can go a long way.