20 years ago, Donnie Darko ruined sci-fi with one tedious trick

One of the worst trends in modern movies can be traced back to Richard Kelly’s 2001 cult classic.

Movies used to be closed circuits. They begin, they end, and the credit scrawl is our signal to leave the theater or stay and find out who played Hotel Clerk #2. But once a movie is over, it’s over.

Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko missed the memo.

Released 20 years ago on October 26, 2001, Donnie Darko defined “cinema” for the generation coming up through high school on its release by mistaking obfuscation for depth. You can watch the film and walk away with a basic comprehension of Kelly’s angsty time travel plot, but you’ll nonetheless have more questions than he has answers.

This likely explains why, in 2003, Kelly published The Donnie Darko Book, 200 pages and change containing his original screenplay, a lengthy interview with Kelly himself, photos and drawings from the movie, and a facsimile document for The Philosophy of Time Travel (the fictional text serving as the narrative’s MacGuffin).

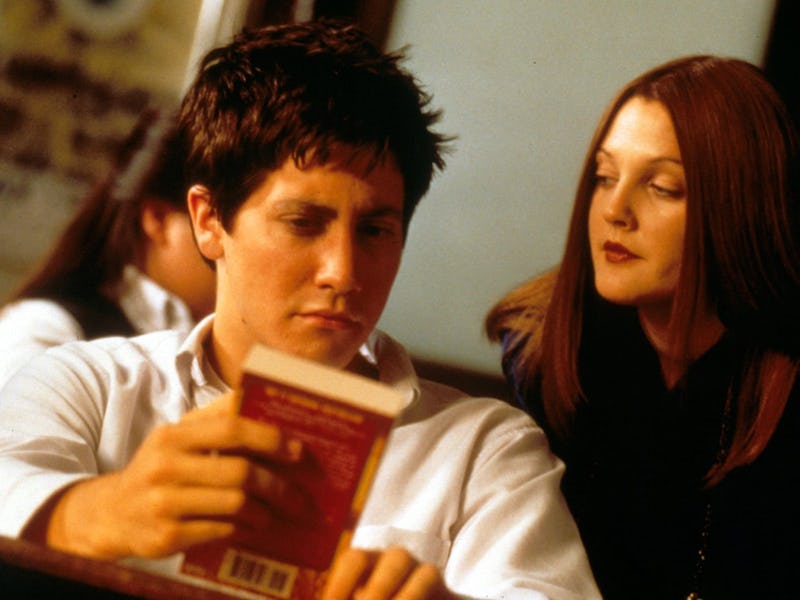

Why a book? The official (and presently nonfunctioning) Donnie Darko website, similarly based on The Philosophy of Time Travel, couldn’t suffice as a resource for unpacking the film’s countless peculiarities. Donnie, Kelly’s protagonist (played by Jake Gyllenhaal in an early lead role), meets a man wearing a grotesque rabbit costume who informs him the world will end in 28 days, 6 hours, 42 minutes, and 12 seconds. Donnie spends that month-long buildup to the apocalypse researching time travel, exposing a child molester, falling in love, and reconciling with his parents. Ultimately, the end – his end – arrives via the business end of a detached jet engine in free fall.

The Philosophy of Time Travel is central to Donnie Darko’s narrative, thus the many efforts over the years to disseminate its contents. But given that the text is so integral to understanding the film, its absence in the theatrical cut feels like an oversight.

The Philosophy of Time Travel.

To Kelly’s credit, he tried to correct the oopsie in his director’s cut, which premiered at the Seattle International Film Festival in 2004. But superimposing excerpts from a book written by a madwoman – Roberta Sparrow (Patience Cleveland), an ex-nun short of all her marbles – over key sequences in the film is an inelegant solution to Donnie Darko’s coherency problems. The Philosophy of Time Travel must be cryptic by its very nature. (“The Living Receiver is often tormented by terrifying dreams, visions and auditory hallucinations during his time within the Tangent Universe,” goes one line, should proof of its riddling quality be necessary.)

In the grand scheme of movie history, these are venial rather than mortal sins. Donnie Darko makes obscure sense without supplementary materials, and the supplementary materials don’t lessen the obscurity. Kelly isn’t the first director to err this way and he isn’t the last. Likewise, he didn’t invent multimedia franchising with Donnie Darko. Together, however, they did make it worse.

Go back to 1999, when Lana and Lilly Wachowski changed pop culture with The Matrix, that seminal sci-fi action blockbuster. A series of comics were commissioned and posted free of charge on the Matrix’s website between 1999 and 2003, the year the third movie in the trilogy, The Matrix Revolutions, premiered. Over time, the Matrix franchise grew to include a host of video game titles, too: Enter the Matrix, The Matrix Online, and The Matrix: Path of Neo. Taken as a collective, they present a cohesive whole, but taken for the movies only, the cohesion remains. You did not, in the early 2000s, need to soak up the ancillary products to retroactively “get” The Matrix. The film worked on its own. Heck, even the convoluted sequels work without doing extra homework.

Neil Gaiman was one of many writers who contributed to the wider Matrix lore.

Now return to our current cinematic moment. The Rise of Skywalker, the embarrassing capstone of J.J. Abrams’ Star Wars sequel trilogy, demands that its viewers read Rae Carson’s novelization to learn how Emperor Palpatine, last seen plunging down a reactor shaft in Return of the Jedi, somehow survived to serve as the antagonist anew. Meanwhile, it’s become impossible to watch the latest Marvel whatsit without revisiting half a dozen movies (and now 6-hour miniseries) beforehand.

Richard Kelly didn’t lead metaseries like these to adopt incompletion as their structural format single-handedly. It isn’t his fault, or Donnie Darko’s, that movies and shows exist that are too thin without accompanying media. But his film did lay the groundwork for a phase in pop culture where storytellers can make up for their shortcomings after the fact instead of getting things right the first time.

This would be unremarkable if not for Donnie Darko’s aesthetic value. Kelly’s film has a singular look and brims with instantly memorable imagery, most of all that rabbit suit, to this day one of the creepiest symbols born from 2000s-era American filmmaking. But the aesthetics are dwarfed today by the enormity of Donnie Darko’s deficiencies, no matter how many times Kelly tried to patch them.