Today’s Big-Budget Sci-Fi Can Be Traced Back To A Forgotten B-Movie

The conquest of space had to start somewhere.

When Paramount Pictures gave producer George Pal a then-sizable $1.5 million to make Conquest of Space, his idea was to create the most realistic film about space travel yet. Released in 1955, Conquest of Space followed several other sci-fi hits — including 1951’s Destination Moon and When Worlds Collide, and Pal’s arguable masterpiece, 1953’s The War of the Worlds — that established Pal as a purveyor of the kind of sci-fi spectacle that still puts butts in theater seats today.

With Byron Haskin, his War of the Worlds director, returning to the center seat for Conquest of Space, Pal went against standard Hollywood practice and eschewed hiring expensive stars for his movie. In fact, the opening credits don’t even list a single actor; the little-known ensemble, none of which distinguished themselves here, was relegated to the end credits scroll.

Instead of spending money on big-name actors, Pal used his budget on four scripts and the film’s visual effects, none of which were ultimately up to par. With the movie based on a non-fiction book by science writer Willy Ley and illustrator Chelsey Bonestell, Pal and his team had to come up with an original story to build around the central premise of a journey to another planet, with different versions of the script cycling through Jupiter and Mercury before settling on Mars as the eventual destination.

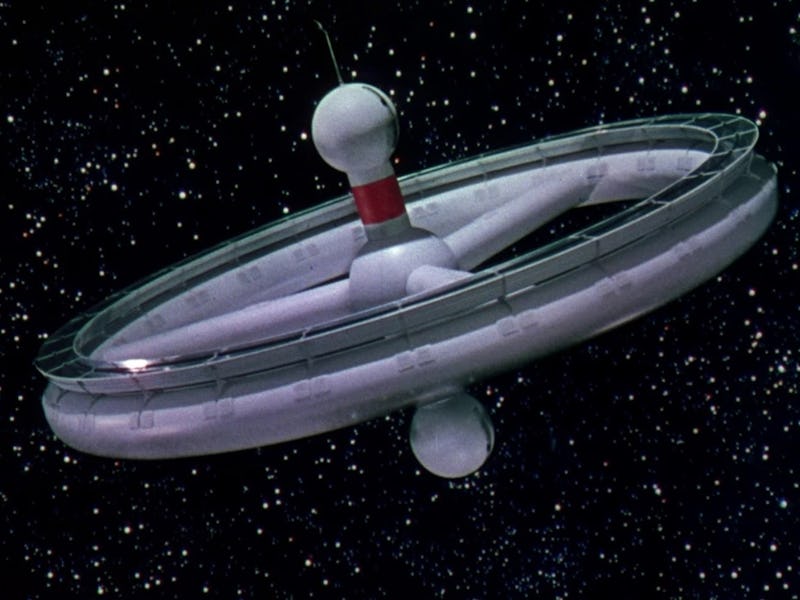

The screenplay that was finally used revolves around an international team of astronauts stationed on a massive space station above the Earth called the Wheel. Their commanding officer, Colonel Sam Merritt (Walter Brooke), is at odds with his son, Captain Barney Merritt (Eric Fleming), who wants to return to Earth to see his wife of three months. But his request is denied by his stony father, as the Merritts and three other astronauts are given new orders to explore the Moon... which abruptly becomes a mission to Mars instead.

Once on their months-long journey, however, the accidental death of a crew member prompts Sam to suffer from “space fatigue” and become a religious fanatic who questions the mission’s purpose. His attempt to end the voyage by crashing the ship on Mars is thwarted by his son, who unintentionally kills his father during the melee. The rest of the crew is then trapped on the red planet for the better part of a year, and when they’re finally able to leave, the surviving astronauts agree to cover up the circumstances of Sam Merritt’s mental collapse and death and instead honor him as “the man who conquered space.”

Albeit on a sort of ‘50s space toboggan.

Some aspects of Conquest of Space are accurate for the era, including the length of time it would take to get to Mars, and certain scenes still make an impact (the funeral in which a crew member’s body is released into space foreshadows a similar scene in Alien 24 years later). Real-life concerns about space travel are addressed (albeit with clunky exposition), and the scenes on Mars are also fairly well-conceived in terms of what scientists knew about our closest planetary neighbor... until it snows near the end, providing the astronauts with much-needed water.

Aside from the overly melodramatic plot and the generally unpleasant characters (some of the “comic relief” is embarrassing), Conquest of Space’s biggest letdown is the special effects. While Chesley Bonestell’s background paintings are striking, the ships and the Wheel are clearly models, and some otherwise impressive scenes of ships and people in space are ruined by thick matte lines. Overly bright lighting (necessitated at the time by the film being shot in Technicolor) only exacerbates the visuals’ hit-or-miss nature. The effects were created by VFX legend John P. Fulton, who worked on James Whale’s The Invisible Man and parted the Red Sea in 1956’s The Ten Commandments, but his work just isn’t as effective here.

Still, give George Pal points for ambition. Conquest of Space certainly feels like it’s striving for a sense of awe and optimism, even if its less-than-stellar cast, insipid script, and weak visuals let it down more often than not. But you can draw a direct line from the movie’s Wheel to the rotating space station in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, released 13 years later. According to Kubrick biographer Vincent LoBrutto, Kubrick screened literally every sci-fi film in existence while developing 2001, and could certainly have been influenced by Conquest’s visual ideas.

In similar fashion, modern movies that deal with the nuts and bolts of interplanetary travel and deep space exploration — exquisitely detailed and immersive films like Gravity, Ad Astra, and The Martian — all carry Conquest of Space’s DNA in them. George Pal’s “B-movie with A-movie values” may not have featured Hollywood stars, but it opened a cinematic path to the stars that sci-fi movies have been following ever since.