The Dumbest Bond Rip-Off Shows How Big 007 Was

“I’ll be at the Judo Range.”

We have Dr. No to thank for starting one of film’s most iconic franchises, although it’s a slow, cheap-looking ride compared to a modern Bond film. At the time of its 1962 release, however, it shook up the spy genre and unleashed a tidal wave of imitators looking to replicate its box-office fortunes. Most, whether serious stories like The Quiller Memorandum, copyright-dodging rip-offs like 008: Operation Exterminate and Agent 077: Mission Bloody Mary, and parodies like the Vincent Price-starring Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine, are long-forgotten. One, meanwhile, is only remembered thanks to its sheer lousiness.

Immortalized by an episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000, Agent for H.A.R.M. sees smarmy spy Adam Chance (Mark Richman) work to foil a Soviet plot to dust American crops with a deadly spore that reduces human skin to a bubbling green slurry. In theory, this involves a cat-and-mouse game between hardline communist Basil Malko and Soviet defector Dr. Jan Stefanik, who’s developed a deadly spore pistol. In practice, it involves a lot of Chance sitting around Stefanik’s house, occasionally stepping outside to shoot at something.

Hitting theaters 60 years ago today, Agent for H.A.R.M. was conceived as a television pilot in the vein of The Man from U.N.C.L.E., before being converted to a one-off theatrical release. The reason for its demotion has been lost to time, although between H.A.R.M.’s general ineptitude and the glut of spy shows already on the air (aside from U.N.C.L.E. and its Girl from U.N.C.L.E. spinoff, televisions were being graced with Get Smart, I Spy, The Avengers, and The Saint, among others), it’s not hard to make an educated guess.

H.A.R.M. is too lousy to recommend even ironically; rather than so bad it’s good, it’s just bad. Richman, a workaday actor best known for appearances in The Twilight Zone, Star Trek: The Next Generation, and Friday the 13th Part VIII, has a certain callous charm, and the film has the odd fun idea, like an eccentric morgue technician who treats his bodies like guests at a hotel. But to call H.A.R.M. glacial would be to insult the Ross Ice Shelf, as the movie drags through interminable conversations and establishing shots with occasional bursts of thrills like “Adam jumps out of a van” and “Adam rides a motorcycle slightly above the speed limit.”

Our suave superspy.

What makes H.A.R.M. fascinating is the insight it offers into a world where everyone and everything was trying to be Bond. From the tortured backronym (Human Aetiological Relations Machine, an apparent reference to the bulky computer that monitors Chase’s medical status) and sci-fi touches to Chase flirting with his boss’ secretary and grappling with a distinctly dressed goon, it’s not even trying to disguise its intentions; a poor example of spy craft. The funky theme music and Chase’s lame gadgets make H.A.R.M.’s franchise aspirations obvious, but while all the pieces are there, they feel like they were dumped in from different puzzles.

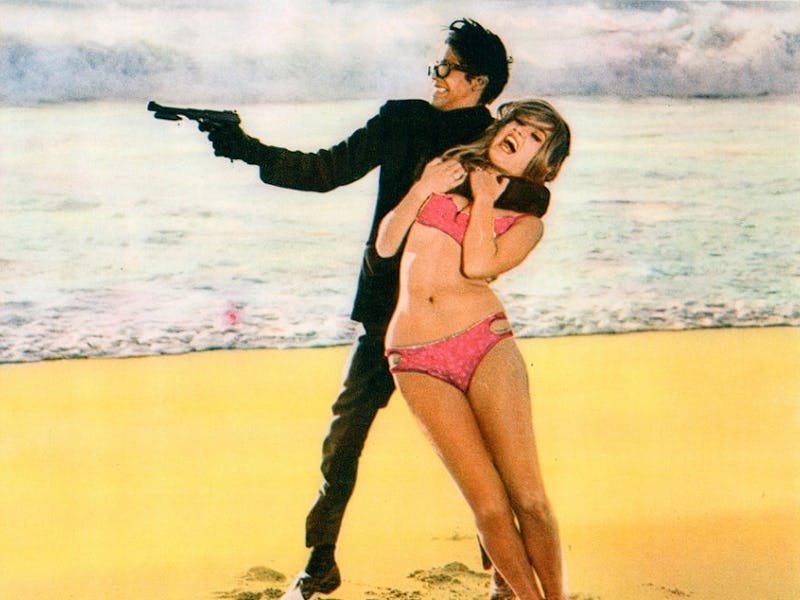

The handful of cheap sets make the film’s financial limitations obvious, but H.A.R.M. is really doomed by odd decisions. Much of the plot revolves around Malko’s attempt to coerce the spore’s antidote out of Dr. Stefanik, even though it appears irrelevant to his poisoning plans. A young, bikini-clad Soviet double-agent (Barbara Bouchet, who would soon play Moneypenny in Peter Sellers’ spoofy Casino Royale) is supposedly an expert archer, but practices with a target set within spitting distance. Even when Chase strangles a goon with a coat hanger, it reads more sociopathic than thrilling. Perhaps the film’s ineptitude is best summarized by a scene where Adam uses his electric razor to secretly record a conversation with Stefanik, even though he has no reason to do so — it just feels spy-y.

It’s not a great sign when your climactic shootout looks like an old Police Squad gag.

H.A.R.M. probably would have been better served as a TV pilot after all — strip out 30 tedious minutes and the budgetary expectations that even B-movies bring, and the thought of seeing a second Adam Chance adventure isn’t offensive. But the last thing the ‘60s needed was another acronymed spook, especially one who spouted insights like “Apple pie and all that jazz? Well, it's my job to keep the pie on the table.” If Bond set the era’s gold standard, then H.A.R.M. fell on its face at the starting line and was promptly trampled by its many rivals.

Amazon’s upcoming Bond reboot is unlikely to generate another batch of movies like Our Man Flint, which told the tale of Z.O.W.I.E. agent Derek Flint tangling with the nefarious Doctor Wu. Barring complete ineptitude from the streamer, however, it will remind us why Bond has shown decades of staying power while his countless imitators fell by the wayside. His critics may gripe that Bond is tired and formulaic, but his formula works for a reason. Decades of attempts to recreate it in Hollywood labs have proven as fruitless as Malko’s attempt to get his hands on that antidote.