Infrared Imaging Is the Future of Finding Invisible Natural Gas Leaks

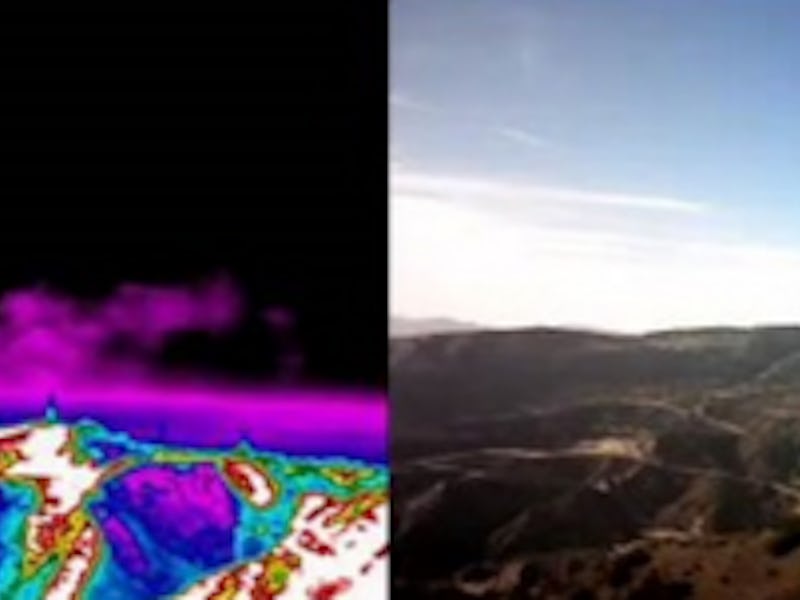

Dramatic video of the gushing Aliso Canyon gas leak points to the value of the technology.

Since October, a ruptured injection well just northwest of Los Angeles has been spewing volatile methane gas at a rate of 62 million cubic feet per day. This is something of a slowly congealing disaster, as methane, the second-most commonly produced greenhouse gas, is a silent killer. Its atmospheric warming power is 80 times that of carbon dioxide across a 20-year period. Odorless and invisible, it often defies simple detection.

But lately, infrared video has allowed filmographers to capture images of methane and other greenhouses gases. The world caught glimpse of the thick plumes jetting up from Aliso Canyon in a video shot and posted online this week by the Environmental Defense Fund. Tim O’Connor, a program director at the EDF, tells Inverse he would like to see infrared tech become part of the standard regulating process in the oil and gas industries because, as he says, it’s highly safe and cost-effective. Many regulators “are already seeing the value of it,” he says.

“The use of Aliso Canyon is really sort of the next step in the direction of understanding major pollution sources and how we can use this technology to see them,” O’Connor says. “What’s happening in Aliso Canyon, combined with the fact that so many people are seeing the value of [infrared], is really going to help overall understanding of the capabilities of the technology and push it further towards mass-market use.”

While infrared technology has long been a military staple, the advent of a lens or camera that can detect harmful pollutants is a relatively recent phenomenon. The hifalutin tech isn’t really the bailiwick of hobbyists, per se — an individual device can run you $90,000 — but players in the oil and gas industries could afford them and head off the consequences of future leaks. The Aliso Canyon leak right now is the greenhouse-gas equivalent of 7 million more cars driving around Los Angeles County.

“Major oil and gas companies that are some of the most profitable companies in the world, have the resources to utilize [infrared tech],” O’Connor says. “We also know that when regulators show up at their doorsteps with one of these cameras and show that it’s going to be part of the regulatory routine, they snap up the technology quickly.”

Strides have been made using infrared processing, and O’Connor says its incorporation in the regulatory process has “been leading to dramatic reductions in pollution,” namely in Colorado. Still, O’Connor is adamant that “there’s Aliso Canyons happening all over the world — maybe not to this extent in terms of a single leak — but there’s a ubiquitous problem of leaking infrastructure that we need to get a handle on.”

Making the process more daunting for the EDF are some EPA prescriptions for relatively arcane instruments to measure gas leaks. O’Connor says these rules are “cumbersome” and often put workers in harm’s way. Infrared, on the other hand, is safer. “You don’t have to send a worker right into a plume,” he says. “You can measure it by standing a few feet away, and you can see it with the naked eye.”

The Aliso Canyon leak will continue until about late February or early March, when the city of Los Angeles and Southern California Gas — the company that owns and operates the facility — can plug the hole.