Scientists discover massive structure connecting the Milky Way's stars

This gigantic stellar nursery redefines how we look at our home galaxy.

When observing the night sky, star gazers look for the most famous constellations in the Milky Way such as Orion, Perseus, and Sagittarius. But hidden from plain sight is a massive, wave-shaped structure that connects star-forming cosmic nurseries together, stretching across trillions of miles above and below our galaxy’s disk.

This week, scientists detailed this gigantic web of gas connecting our nearby stars together for the first time. They also created the most accurate 3D map of our galactic neighborhood ever produced, detailing the distance and position of the stars within it. The discovery fundamentally alters astronomers’ conception of nearby stars in the Milky Way, and may prompt a rethink of an age-old view of our galaxy.

The incredible structure, described in the journal Nature this week, is dubbed the Radcliffe Wave after the Radcliffe Institute For Advanced Study at Harvard University, where the team behind the collaborative study originates.

Hidden in plain sight

Catherine Zucker, a graduate student at Harvard University’s Department of Astronomy, and an author of an earlier study that led to the discovery of the Radcliffe Wave, describes it as the largest coherent star-forming structure of its kind.

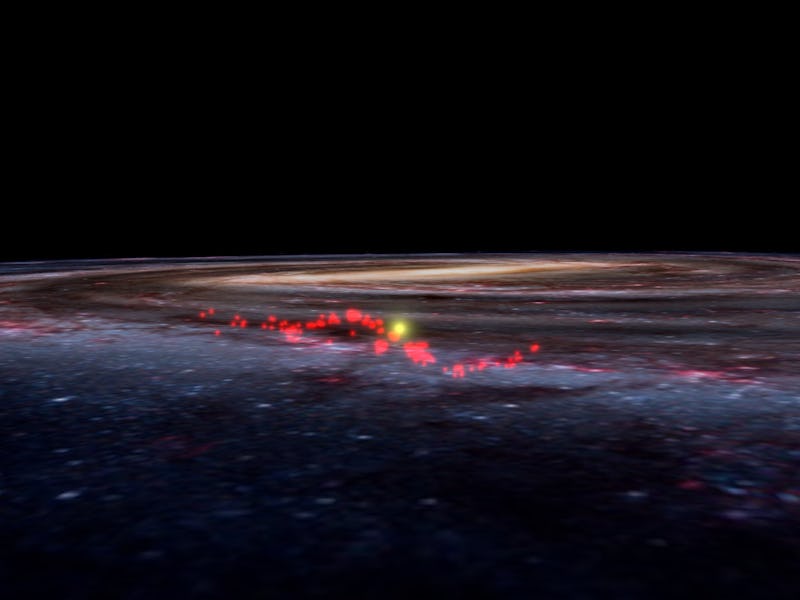

The Radcliffe Wave was discovered along the spiral arm of the Milky Way closest to Earth. The yellow dot represents the Sun.

“All of the star constellations that people have been studying like Orion, most of them are connected in ways we’ve never seen before,” Zucker tells Inverse.

The researchers used data gathered by the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft, which launched in 2013 to accurately measure the positions and distances of nearby stars. First, they created a 3D map of interstellar matter in our galactic surroundings. By looking at that map, they noticed something unexpected: A pattern that had previously eluded scientists near one of the Milky Way’s spiral arms —the one closest to Earth. It turned out to be the structure that makes up the Radcliffe Wave.

“At first, we didn’t actually believe that it was real because it’s gigantic,” Zucker says. “We were in shock, this thing is right under our noses.”

You can explore a 3D view of the newly discovered Radcliffe Wave here.

Surfing the Radcliffe Wave

The Radcliffe Wave is around 500 light years away from the Sun, stretching in the shape of a long, thin, S-like structure. It is about 9,000 light years long and 400 light years wide. The wave is made up of stellar nurseries, interconnected through filaments of gas which themselves stretch 500 light years above and below the mid-plane of the Milky Way’s disk.

In this image, filled circles indicate the Radcliffe Wave's stellar nurseries. The unfilled circles indicate the connections between nurseries.

The reason why we have had no idea it was there until now is because it is only visible from Earth when looking in three dimensions, the researchers say. Similar structures have been observed in other galaxies, but never quite so large, nor so linear.

The researchers are still trying to figure out exactly how it formed, but there is one leading theory.

“One scenario is that it’s possible there was a collision between the Milky Way and smaller, dwarf galaxies,” Zucker says.

If that is the case, then the Radcliffe Wave could possibly offer clues to ancient galactic collisions between the Milky Way and its smaller neighbors. Galaxies often exist in groups, and if one large galaxy happens to have an equally large or smaller sized galaxy next door, then their gravitational pull will inch them closer and closer together before they eventually collide.

It is also unclear how old the Radcliffe Wave is, but scientists discovered that it is still producing stars — in fact, the massive structure is currently home to tens of thousands of baby stars.

The wave could help astronomers better understand star formation and whether or not these interconnected webs of stellar nurseries are common throughout the universe.