New technique could reveal 'hidden' exoplanets scattered throughout the cosmos

The break from traditional methods has already bear fruit for exoplanet hunters.

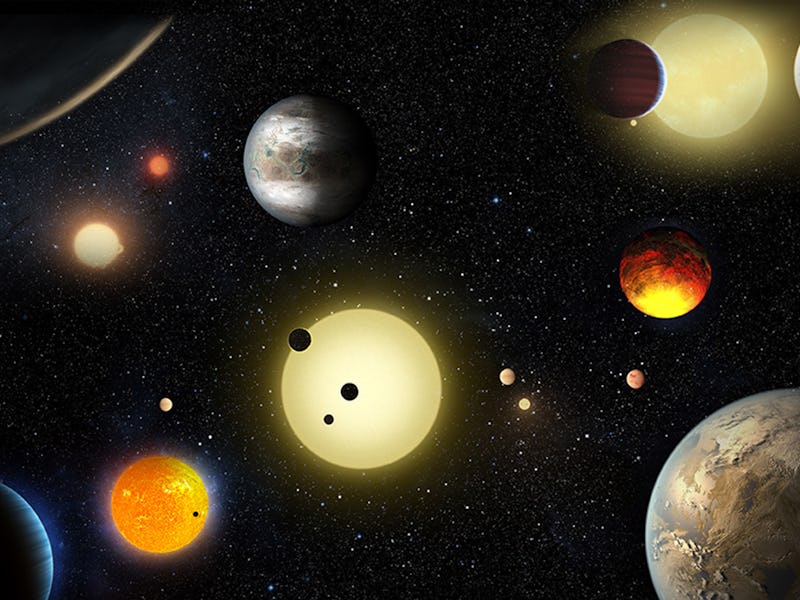

Since the discovery of the first exoplanet in 1992, astronomers have been on the hunt for these alien worlds, finding thousands of them all over the cosmos. But there are some that — though they should exist — we just haven’t been able to spot.

One such planet type are low mass, rocky planets that orbit very close to their host stars. But in a study published this week in the journal Nature Astronomy, a team of astronomers claim a new technique to detect these planets could result in a new exoplanet bonanza.

Rather than trying to find the planet by chance, the method targets seemingly misbehaving stars and predicts what kind of planets could be orbiting around it. It could enable astronomers to find a whole new population of exoplanets, and offer a better understanding of our own planet.

Already, the new technique has yielded six new exoplanets, the researchers say.

Searching for exoplanets

Carole Haswell, professor of astrophysics at The Open University in the United Kingdom and lead author of the study, was observing a known hot Jupiter exoplanet by the name WASP-12b back in 2009 when she noticed something odd about its host star.

“The star that had this very rare planet orbiting around it that looked completely different to all other stars of the same type,” Haswell tells Inverse.

A star like the Sun has a chromosphere, visible as a rim of rosy-colored light during a total solar eclipse, as the second layer of its atmosphere. But the host star of WASP-12b appeared to be missing its chromosphere.

“It seemed to me very unlikely that we have a situation where there’s this very peculiar star that’s structured differently than all other stars, that also hosts a very rare type of planet,” Haswell says.

Instead, Haswell hypothesized that the planet, which was losing mass because it was orbiting too close to its star, was forming a gas shroud around the star from the mass that was escaping it — obscuring Haswell’s view.

Previously 'hidden' exoplanets may soon come to light thanks to a new technique.

When you shine a light through gas, the chemicals of that gas absorb the light and imprint their chemical signature on it, she says. In this case, the gas shroud emitted by the planet absorbed the light of the star’s chromosphere.

From there, Haswell and her team began looking at other stars that appeared to be missing their chromosphere.

They started with a sample of 6,000 bright stars then narrowed it down to 2,700 stars structured the same way as the Sun. Out of the 2,700, 40 stars appeared to be missing their chromosphere.

“My hypothesis was that those 40 stars are also hosting very hot exoplanets that are losing mass, basically being baked alive by the star that they’re orbiting very close to,” Haswell says.

The team found a total of six low-mass, rocky planets from a total of 148 observations between December, 2015 to January, 2018.

A new approach yields new discovery

Their method is unique in its targeted approach: Traditionally, astronomers look for exoplanets by observing a large number of stars, surveying them every week or so to look for exoplanets. But in this case, the team selected target stars. They also had clues as to what kind of planets they might find, allowing them to tailor their observations specifically for them.

“It’s the first time that anybody has been able to use clues from just the starlight to figure out which planets are present,” Haswell says. “The thing that’s remarkable is how successful it has been.”

Interestingly, one of the planets they found orbited a star originally observed about 10 years ago. The planet, which is half of Jupiter’s mass, came as a surprise to Haswell, who thought that all planets of its size around the star had already been found.

“But because the star had been misbehaving, it was tough to measure the velocity,” she says. “People had looked at it 10 years ago [and thought] this star is not behaving well, let’s move on to something easier.”

The method also allows scientists to get a rare look at the composition of these far-away planetary bodies. Because the planets are essentially being evaporated by their host star, astronomers can use spectrography to figure out the different materials being lost from the planet.

“That gives us a lot more information about what planets are made of, how they’re built and…how planets form and devolve,” Haswell says.