Apps Have Made It Easy to Shame Your Non-Voting Friends, but Should You?

It's easier than ever to shame your non-voting friends.

When it comes to political organizing, the data suggests that being annoying can be effective. This thinking follows the wildly successful (and widely mocked) email marketing operation that helped then-presidential candidate Barack Obama pull in close to $700 million in online fundraising ahead of the 2012 election.

By 2018, the conversation about getting people to vote and contribute has moved to text message, which is even more effective: A study by the non-profit Vote.org examined close to a million voters, some receiving emails and some receiving “aggressive” SMS reminders, and found that people who received texts were about 65 percent more likely to show up at the polls.

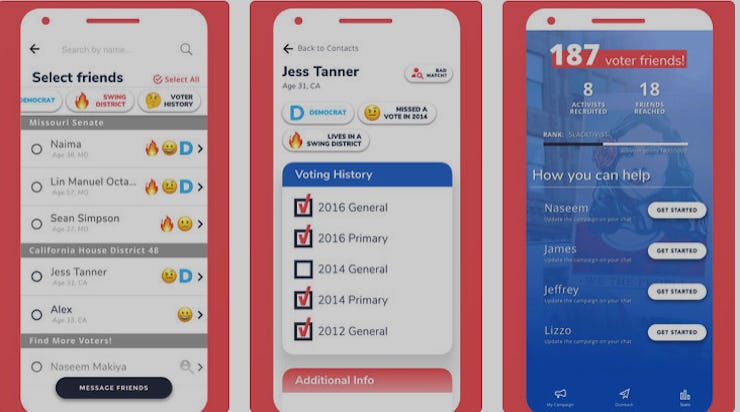

To help you text out the vote, OutVote is here with a new app that makes it easier to prioritize who you reach out to by combing your contacts list and checking it against publicly available voting records. Some states make this information easier to access than others, but depending on where your friends live, OutVote can tell you things like whether they are registered in a swing district, their party affiliation, and whether or not they’ve voted in certain elections and primaries.

OutVote’s founder told the New York Times that the object wasn’t to “shame” voters, but this sentiment isn’t always mirrored in the app’s design, which places an “eye roll” emoji next to non-voters and a sleepy emoji next to infrequent ones. Election privacy experts have even raised concerns about whether making this information — which has always been gathered by pollsters but traditionally has not been super public — too far out into the open has the potential to backfire.

“I don’t think there are any particular safeguards to prevent people from just assembling a contact list for more malicious purposes, acquiring this information and using it to harass or coerce people,” Ira Rubinstein, a fellow at NYU Law who studies election privacy, told the Times.

But on the other hand, the fear of being outed as a non-voter might be one of the most effective ways to get people to turn out. That’s according to a 2008 [study]https://isps.yale.edu/sites/default/files/publication/2012/12/ISPS08-001.pdf), written by researchers at Yale and the University of Northern Iowa, which compared the effectiveness of mailers that encouraged voting as an act of good citizenship with mailers that warned voters that they were being studied. Mailers that promised to publicize household voting records to their neighbors were far more effective at increasing turnout, adding evidence to the idea that social pressure is an important motivator for getting people to the polls.

And even on a hotly contested Election Day filled with down-to-the-wire contests, lots of eager voters can still feel like they’re watching history unfold from the sidelines. Only 80 or so out tomorrow’s 435 congressional races are competitive, according to BallotPedia. That’s lots of people eager to be involved who don’t necessarily have a competitive race that they can vote in.

It’s important, then, that the people who aren’t lucky enough to live in an exciting election district or near candidates that inspire them have ways to feel politically engaged without having to donate money, which, after all, is expensive for people with tight budgets. Texting friends to get out the vote is a worthy way of doing so, and it’s probably good that there are increasingly better resources for would-be volunteers who want to know that their time is well-spent.

Just bear in mind that not everyone shares your zeal for the American electoral system, and coming in hot with a series of judgmental texts is unlikely going to be the best way to change that.