DFW, FTW: Rename the Dallas/Ft. Worth Airport for David Foster Wallace

No airport is named after an American author. Let's change that.

This is a major week in the legacy of author David Foster Wallace. With the release of the movie The End of the Tour, adapted from author David Lipsky’s book Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, the late author enters into the tiny pantheon of writers immortalized in their own movie. For what it’s worth, people seem to think it’s a fairly great tribute to his tortured genius. But then, it is only a film. Wallace is among the preeminent literary voices of the past generation — surely we can do him better than to position Jason Segal for a Golden Globe nomination. Let’s aim bigger. Like Americans. Or bigger yet: like Texans. It’s high time to honor Wallace on a canvas befitting his stature. Let’s go bold and Infinite Jest big. We’re thinking: The David Foster Wallace International Airport, airport code DFW.

Hear us out.

Louis Armstrong has an airport. Bob Hope has an airport. John Wayne has an airport. Charles Schulz has an airport. Ian Fleming even has an airport in Jamaica. So why not David Foster Wallace? When will America honor the airport novel with a novelist airport? Now seems about right.

Enter the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. It’s one of the top 10 airports in the world by size and by passenger traffic, and unlike many of its peers — Heathrow, O’Hare, Hartsfield-Jackson, JFK, Dulles, Reagan, Bush — it doesn’t yet have a namesake. It also carries the letter code DFW, the prefix assigned by the International Air Transport Association, which just normalizes the easily recognizable codes for travelers on baggage tags, check-in desks, maps, etc. Some of these make perfect sense — JFK for John F. Kennedy Airport, LHR for London Heathrow, ORY for Orly in Paris, LAX for Los Angelex, and so on. But others are kind of baffling — ORD for Chicago’s O’Hare or MCO for Orlando International are semi-head-scratchers. Yet DFW is there like a gift from the literary gods, held in place by two great American cities with downright fantastic-working initials.

Some people would say such a change is outside of the realm of possibility — we know; we ran this idea past them, and they used that exact phrase in a bit of a huff. But then, logical validity is not a guarantee of truth. The IATA usually doesn’t change airport codes, due to inertia. Switching codes confuses employees and travelers alike. Such is not the case with DFW. The real hurdle is convincing the airport’s board of directors of the merits of sharing the name with an American author. That seems, to us, quite surmountable.

Because the airport is owned by the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth, and operated by a board of directors comprised of businessman and the mayors of both cities, the reality of the David Foster Wallace International Airport, née Dallas/Ft. Worth International Airport, comes down to that handful of folks. Perhaps a few copies of Infinite Jest would sway them toward becoming an instant international literary destination (or layover).

But the connection between author and airport goes beyond the monogram. This is a match that has deeper roots.

Naming an airport, among all the available infrastructure, after David Foster Wallace would be oh-so wildly appropriate given its relation to his considerable body of work. Had he lived another decade, it’s perfectly reasonable to imagine Harper’s or Conde Nast Traveler would’ve assigned him a 9,500-word (plus footnotes) vivisection of a week spent in the terminals there, circa Thanksgiving.

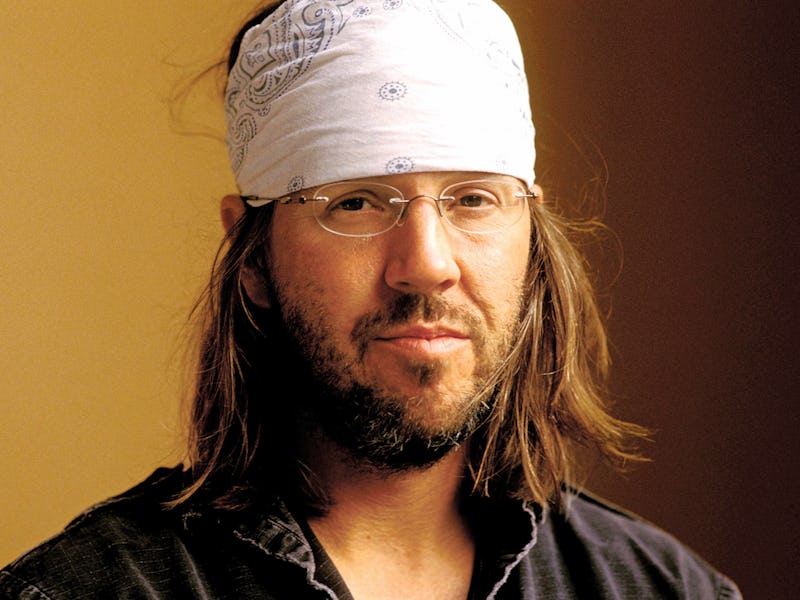

Wallace

Wouldn’t it be the piece de resistance of literary integrity to create the living embodiment of his ridiculously savvy yet sardonic work in a real place for everyone to experience? He was a master at deconstructing the bureaucratic absurdities of American social behavior in confined spaces, and that was just his non-fiction. Reading Wallace makes a person feel more insightful, more aware — and calmer — in the face of a supposedly fun thing you never want to do again. Wallace made us all happier travelers. His narrative voice was not one to raise hell at minor inconveniences, to berate a worker for things out of either of their control. He would have been the sort of person you want to see more of at your gate.

In its review of his posthumous novel, The Pale King, the Los Angelex Times wrote that the book “dares to plunge readers deep into [a] Dantean hell of ‘crushing boredom,’” a perfect companion tome for Terminal B — for in that very book, Wallace writes of surviving the vicissitudes of air travel. “To be, in a word, unborable,” he wrote, “it is the key to modern life. If you are immune to boredom, there is literally nothing you cannot accomplish.”

Wallace celebrated the beautiful complexities in even the most quotidian systems. Here he is in Harper’s in 1991:

I’d grown up inside vectors, lines and lines athwart lines, grids — and, on the scale of horizons, broad curving lines of geographic force, the weird topographical drain-swirl of a whole lot of ice-ironed land that sits and spins atop plates. The area behind and below these broad curves at the seam of land and sky I could plot by eye way before I came to know infinitesimals as easements, an integral as schema. Math at a hilly Eastern school was like waking up; it dismantled memory and put it in light.

He’s talking about playing tennis while growing up, but he could just as easily be talking about the beauty of flight patterns. He was, in his way, the patron saint of slowing down and paying attention. He sublimated the inevitable frustrations of life into a sort of intellectual fuel. “The really important kind of freedom,” he told Kenyon College grads in 2005, “involves attention, and awareness, and discipline, and effort, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them, over and over, in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day.” Any airport would consider itself lucky to live by such words.

Sunrise at DFW

Best as I can tell, Wallace had a tenuous relation to the Dallas/Fort Worth area, but he has Texas connections nonetheless. He was born in New York, grew up and eventually taught classes in Illinois and California, and went to school in Massachusetts and Arizona — truly a man who belonged to America at large, though, in death, Texas most of all. His papers were bought by the University of Texas after his death. And for what it’s worth, his one-time partner Mary Karr was raised in Texas and set her 1995 memoir, The Liar’s Club, in the Southeast region of the state.

What do the locals think? When I reached out to bookstores, regional writers, literary agents, and the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport board members, I was met with the telltale lack of enthusiasm or even comprehension that so often announces that a forward-looking idea’s time has truly arrived. John Tilton, the owner of the Dallas independent bookstore chain Lucky Dog Books, sounded a note of skepticism. “Dallas isn’t a literary enough place,” he told me. “Ten percent of people would know who (Wallace) is.” Like the sky itself, there’s nowhere to go but up for this notion.

This could be the Incandenza International Concourse.

Tilton seemed at least intrigued by the idea, if not totally sold. “You’re talking about the entirety of Dallas and Fort Worth,” he said. “People think of this entire north Texas area as a quote-unquote metroplex. It’s almost 40 or 50 miles around, and as someone who’s 60-years-old and knows these people, if [Wallace] doesn’t have a connection to the area, it’d be a nice symbolic thing, but it just wouldn’t work.”

He offered a reasonable compromise between staid reality and the vision of tomorrow I was offering. “You should talk to the people at the airport about naming a lounge after him — it’d be great to have facsimiles of his work and artifacts from his life there to honor him,” Tilton said. “That would be great.”

A lounge wouldn’t be bad at all. But what about the other 17 square miles of airport, a nexus of humanity that handles more than 1,700 flights daily? We say there’s a chance — and, yes, a White House petition. Let’s make this happen, fellow readers. How better to honor Wallace and, yea, all of literary America? What other venue is as convenient and ready and waiting and obvious enough that it might as well grab you by the collar and kiss you full on the lips?

The letters DFW will always stand for Dallas/Fort Worth — the very names of the towns ensure as much. But they could mean even more. Dallas, you know what to do. Fort Worth, the ball’s in your court. You’re the only twins big enough to make room like this. No other cities can do it. No other cities could do it. Embrace the David Foster Wallace International Airport. No jest.