Missouri's ‘Hotel Influenza’ Wants to Pay You $3,500 to Catch the Flu

“This method of study has been used for nearly 100 years.”

If you call the Water Tower Inn in in St. Louis, Missouri, an automated voice will pick up the line. “Thank you for calling the Water Tower Inn,” it says. “We are now permanently closed.” Don’t let the that automated voice fool you, because there are still guests staying there, and they’re probably feeling a bit ill.

The Water Tower Inn in St. Louis — now a part of St. Louis University’s Salus Center — is an “extended stay research unit,” in which guests can earn $3,500 by allowing researchers to expose them to flu virus and watch what happens. At “Hotel Influenza,” volunteers are exposed to either a placebo or a live flu virus, allowing researchers from the university’s Center for Vaccine Development to study how the flu slowly overtakes humans. After about ten days — or until they are no longer contagious — the volunteers will be set free. The architecture of this study represents the newest phase in a trial method with a complicated history: The “human challenge study” is one of the few study designs in which researchers expose real-life, healthy people to infectious disease. Crazy as it sounds, Matthew Memoli, Ph.D., Director of the NIH’s Laboratory of Infectious Disease Clinical Studies Unit, tells Inverse that this method of study “has been used for nearly 100 years.” That’s not to say it was always as safe as it is now, though. “In the last 10 years, I think you are seeing the development of modern healthy volunteer challenge trials at the highest level of ethical and safety standards,” he says.

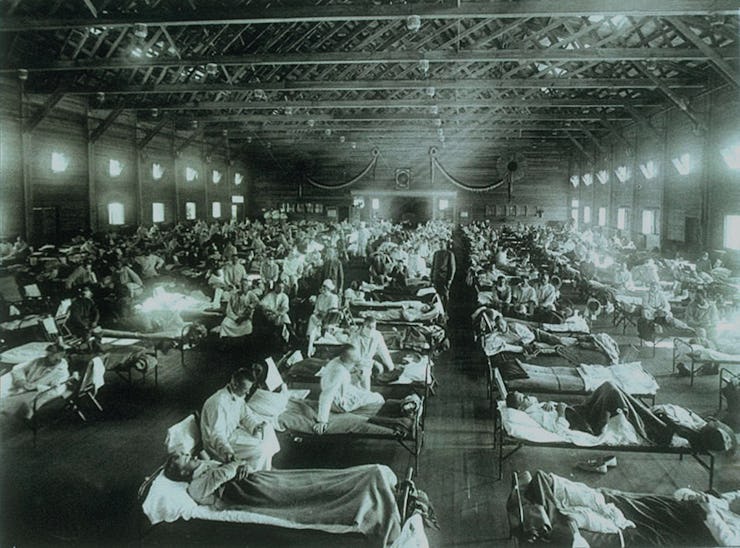

High death rates during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic prompted researchers to attempt new kinds of trials to develop a vaccine.

The first notable human challenge study was conducted in 1936, when two Russian doctors exposed 72 volunteers to influenza. The results of this study helped researchers discover that flu tends to enter the body through the lower respiratory tract as well as other crucial elements of “vaccine strategy,” according to Memoli. But the ethical considerations of exposing healthy subjects to disease became even more complicated in 1946, when evidence of the twisted Nazi experiments on healthy individuals came to light during the Nuremberg Trials.

The World Health Organization has since issued strict guidelines for human challenge studies. Despite these guidelines, human challenge studies have remained rare in the United States. Memoli was one of the first to conduct a human challenge study for roughly a decade when he published his findings in 2014. The current trial is the next step in what Memoli sees as a resurgence in this controversial method of study.

“In influenza, we can learn about immune response because we can study it from the second someone is exposed to flu in a challenge trial,” he says. “This cannot be done in any other way because by the time a person presents to a doctor with a natural flu infection many hours and usually days have gone by.”

While the human challenge trial at the former Water Tower Inn in St. Louis may not have the notoriety of its predecessors, it represents an important step in the reemergence of a type of study that, in Memoli’s words, “can be very important in allowing us to understand infectious disease.”