Google’s Quantum Simulator Gets Real Trippy And Generates A Butterfly

Quantum simulators can be artists too.

Right when you thought quantum simulators could only crunch numbers, they throw on a drug rug and start making tapestries.

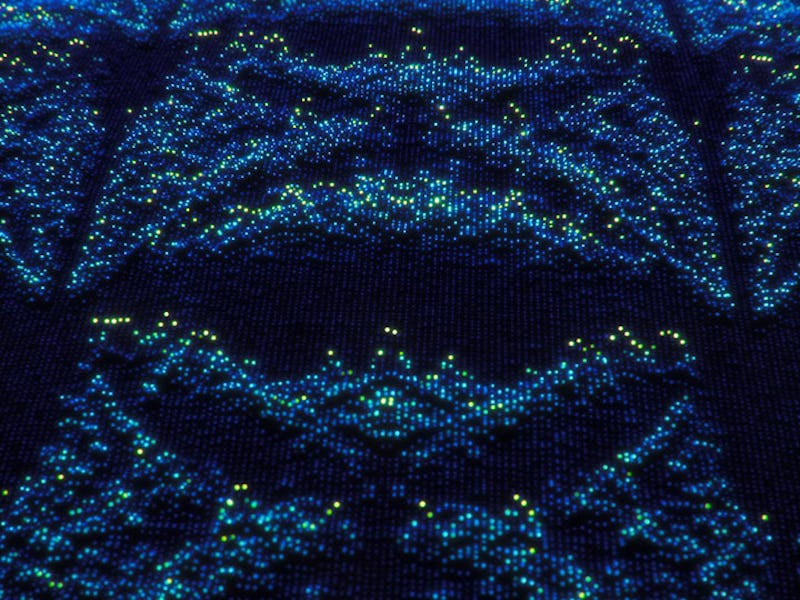

This psychedelic image isn’t just something to stare at after a couple of bong rips. It’s called the Hofstadter butterfly and it’s actually a map of how electrons behave in a strong magnetic field. Every split and shift of these subatomic particles are beautifully rendered by the photons inside of Google’s quantum chip.

The Hofstadter butterfly was discovered in 1976 and has always been nothing more than an educated guess of how electrons ebb and flow inside of a magnetic field. With this collaborative research effort by Google and scientists from universities in California, Singapore, and Greece, published Thursday in Science, we now have a much better idea of what this phenomenon looks like.

Old rendering of a Hofstadter butterfly. 1976

This was all made possible by quantum simulators, which are special-purpose quantum computers. They can’t solve any problem like still theoretical quantum computers could, but they can be used to solve specific problems.

The issue at hand here was that conventional computers could not accurately map particles this unimaginably small. Google’s quantum simulator runs on photon qubits, instead of binary bit. Those qubits are also subatomic particles, which allow them to create a more detailed image of the Hofstadter butterfly than traditional computers have ever been able to.

“Our method is like hitting a bell. The sound it makes is a superposition of all the basic harmonics,” Dimitris Angelakis, a researcher at the Center for Quantum Technologies in Greece, explained in a statement. “By hitting it in different positions a few times and listening to the tune long enough, one can resolve the hidden harmonics. We do the same with the quantum chip, hitting it with photons and then following its evolution in time.”

The results of this research not only produced a dank butterfly, but it also shows how quantum simulators can be used to visualize naturally occurring phenomena in the world around us. Similar to how seeing is believing, seeing is oftentimes understanding. Being able to clearly envision the infinitesimal particles and forces that make up the world can lead to a better comprehension of how they work and interact with each other.