The Robots Taking Factory Jobs Just Had Their Best Quarter Ever

Robot sales are booming. But the faster they grow, the quicker jobs will go.

The North American robotics industry had its best first quarter ever in 2017, in terms of both money made and robots sold.

A new report published last week by the Robotic Industries Association finds that “an all-time high total of 9,773 robots valued at approximately $516 million were ordered from North American robotics companies during the first quarter of 2017.” It marks a 32 percent increase in units sold from the first quarter of 2016 and 28 percent growth in the value of the units.

There was also a 3 percent decrease in the average price of these units over the same time. Robots are getting cheaper and people are buying more of them.

All those statistics add up to great news for robotics companies and their clients, who can see their businesses become more efficient and keep up with customer demand. A $516 million dollar Q1 showing is more than enough to seat robotics in the echelon of billion dollar industries, and its continued expansion, based on past trends, is all but assured.

But where will that new wealth go? It’s here that industry growth could spell bad news for individual workers in jobs — even beyond manufacturing — that will be hit by automation. It’s bad news that many, including former President Barack Obama, have already foreseen. “The next wave of economic dislocation won’t come from overseas. It will come from the relentless pace of automation that makes many good, middle-class jobs obsolete,” said Obama in his farewell address, zeroing in the problem.

A study released in March confirmed that automation is eliminating jobs faster than new ones can emerge.

The trend has the potential to seriously impact Rust Belt and specific-skill workers over the long term, wrote co-authors by Daron Acemoglu of MIT and Pascual Restrepo of Boston University.

Acemoglu told Inverse in March that “robots are less complementary to a distinct set of skills that exist in the labor market at the moment than previous technologies.” They are more likely to replace workers, rather than augment their skills as inventions like mechanical looms and computers did in the past.

The study also showed that unemployment rises at a disproportionately high rate for each robot added. It’s not a 1-to-1 trade-off. Adding one robot to a group of 1,000 workers, they found, would increase the unemployment rate by .18 to .34 percent (if it was 1-to-1 they would have seen a .1 percent drop in employment per robot per thousand workers). A single robot could replace up to three or more human workers, depending on the industry.

The first quarter of 2017 saw nearly 1,000 robots purchased. It could be nearly 1,300 robots purchased in Q1 of 2018. That could cost over 3,000 jobs in Q1 alone. While those numbers may seem small now, given the 211,000 jobs created in April, they will grow quickly.

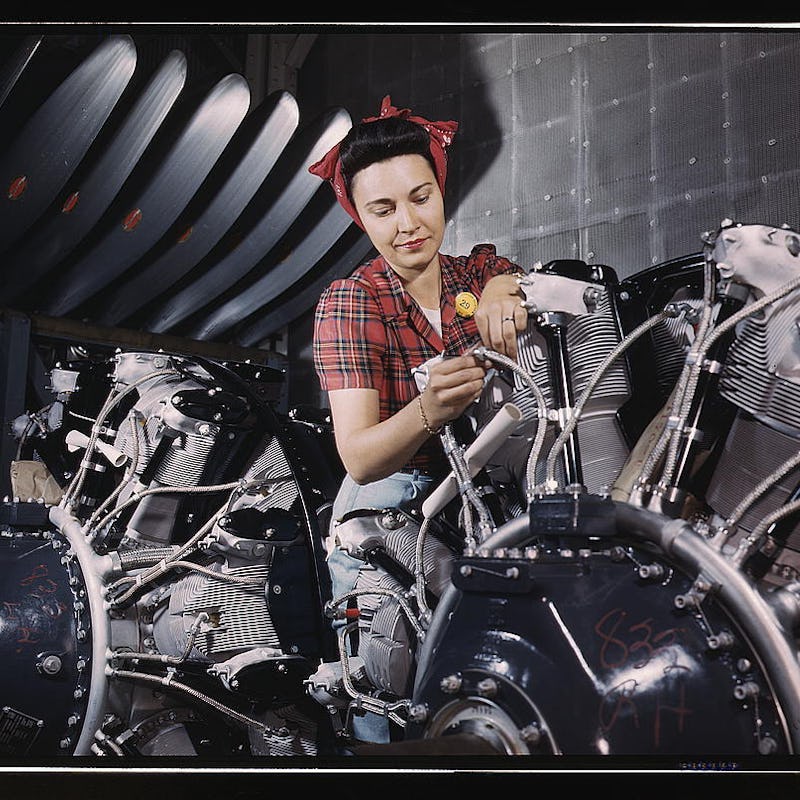

Factory workers in 1945 in Washington state.

The strength of America’s economy is often measured through employment statistics. But the continued rise of automation could upset that metric, creating a paradox. Whole companies, thanks to the cheaper, safer, and more efficient labor of machines, will continue to profit — maybe even more than they are now. But workers, left to compete for fewer positions, will keep losing their jobs.

One industry watcher sums it up as dystopian. Ben Wardell, founder of software company Stardock, warned in 2016 of a coming division between The Gods and The Useless. He writes in a blog post, “I am telling you the automation revolution isn’t happening soon. It’s happening right now.” And Wardell says we aren’t ready — we’re “oblivious.”

A crossover SUV vehicle is welded by robot arms as it goes through the assembly line at the General Motors Lansing Delta Township Assembly Plant in Michigan.

But few real solutions have actually been suggested, perhaps because Americans still don’t see it as a problem that will affect them personally. “Automation is generally a good thing if you educate workers,” said Ian McCormack, one of 15 blue-collar workers at a Trump rally interviewed by Inverse during the 2016 election.

As things stand, that’s a big “if,” since no policies to that effect have yet emerged.

The responsibility could simply fall to business leaders. It’s been done before. Chieh Huang, CEO of Boxed.com recently automated his warehouse without shedding a single worker. In fact, he gave some of them promotions. Huang told Inverse, “Instead of just saying, ‘you’re not going to lose your job,’ I actually wanted this to be an opportunity for folks to learn a skill that’s going to be really important in the future.” It’s a laudable move, but Huang has only 85 employees. The question remains whether the heads of much larger companies will show similar fidelity.

Elon Musk interviewed by Chris Anderson at TED2017.

Some, like Elon Musk, have put forward out-there policy ideas. “This is going to be a massive social challenge,” Musk said in February at the World Government Summit. “And I think ultimately we are going to have some sort of universal basic income. I don’t think we have any choice.”

Workable solution or not, Americans may soon find themselves facing a new kind of economy: One that’s flush with productivity and cash but is simultaneously inaccessible to the increasing numbers of people whose skills are obsolete.