Micro Drone Racing is Taking Off

They're small, it's highly technical, and a lot of fun.

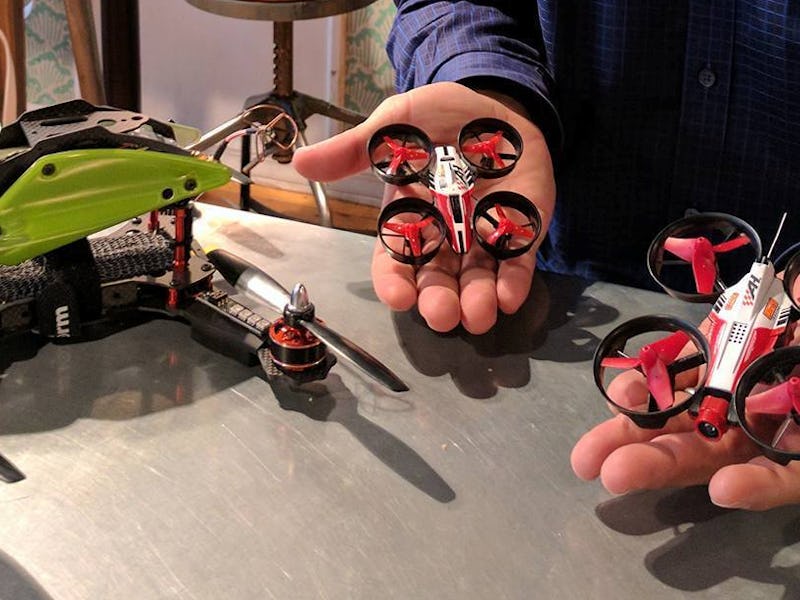

At first glance, a micro drone doesn’t look substantial. It’s small and can fit in the palm of your hand. Its rotors look like four tiny wheels. But don’t underestimate it — these micro drones are going to be the future of drone racing and become the new racecars.

These miniature mean machines can accelerate from 0 to 20 mph in two seconds, and unlike regular racing drones, you don’t need a pilot’s license to fly them. That’s why Brad Foxhoven, founder and CEO of drone racing organization DR1 Racing, wants to create a racing platform for micro drones to make the sport more accessible to the public.

DR1 Racing is starting the DR1 Micro Series, the largest micro drone race in the world, which DR1 will start filming this month. The series will debut on TV later this year.

In comparison, regular racing drones can accelerate to 60 mph and usually fly outdoors, but they must pass various federal regulations.

“It’s an extraordinarily fast machine, very difficult to fly. It requires a lot of technical ability,” Foxhoven tells Inverse. “If it crashes, you’re your own mechanic. You not only need to know how to fly it, you need to know how to repair it. That’s a big challenge for a lot of people to learn and do, and there’s lots of FAA regulations around this.”

However, micro drones are safer to use, easier to fly and fix, and can be flown indoors. “It allows a choice for actual enthusiasts to fly and allows the fans to get in,” Foxhoven says.

The green drone in the back is a regular racing drone, which can accelerate from 0 to 60 mph. The red and black drone in the back is a micro drone, also used for racing. The drone in the front is an entry-level drone, which is smaller than the other two drones. Unlike the other two drones, the entry-level drone does not have a camera and is flown at line-of-sight.

DR1 recently debuted micro drones at the Toy Fair in New York City in February, since drones are becoming more popular. This past Christmas season, drones were one of the most popular toys. Some kids are even learning how to fly drones as young as age six, and by the time they’re teenagers, they’re already pilots.

“Because of the regulations over here, the challenges, difficulty, and expense, it makes it harder for someone to become a competitive pilot,” Foxhoven says. “By starting here (with micro drones) and starting with a younger culture, they’re learning how to fly earlier.”

Right now, some of the best drone racers, like Luke Bannister of the UK, who became one of the world’s top racers at age 15, are quite young and got their start from childhood. The Micro Series does not have a minimum age requirement, allowing the sport to open up to young people.

“In this [sport], I don’t need to be the biggest or strongest or fastest. I just have to be really good technically at flying,” Foxhoven says. “If I am a great pilot, I will be found and grow as an athlete in this medium, and that’s pretty compelling for a kid. I’m not that kid who’s able to dunk in 6th grade. I’m just a regular kid, but I can fly.”

According to Foxhoven, this racing series will reach over 100 countries. Right now, there are nine pilots racing, but newer pilots will have the chance to enter and compete in the race.

Brad Foxhoven, founder and CEO of DR1 racing, holds the entry-level drone on the left and the micro racing drone on the right. The drone on the table is a regular racing drone, which is used in the DR1 Champions Series.

In the Micro Series, DR1 plans to build creative, 3-D tracks since the drones will be flown indoors (3-D meaning there will be gates, caverns, and barriers in the air also). Each track will have different themes, like a sci-fi theme, superhero theme, and more. What’s more, something special about this race is that pilots can customize their own drones.

“The type of prop, the battery, the frame, it’s an art because they are building the perfect machine for their racing style,” Foxhoven says. “When you think about traditional driving, the driver thinks about the tires on his car, the steering wheels he uses, the brake differential he has, the gears in his car. There’s still a standard format obviously, but there’s customization that makes a competition interesting to a viewer and the pilot.”

The other major league, the Drone Racing League, gives pilots the same drone, so the race focuses more on the pilots’ flying skills.

But for many drone racers, Foxhoven says, customization is an important aspect and a way for pilots to express themselves and pilot better. Similarly to how racecar fans are attracted to different racecar models, Foxhoven believes allowing pilots to customize drones will make the sport more popular.

“It’s like saying in basketball, we’re going to give everyone the same shoes, but some like a little more grip, some like it a little slick, some like the heel thicker or thinner,” Foxhoven says. “It gives them a psychological advantage perhaps. We believe that’s a good thing for the sport.”

Foxhoven hopes drone racing soon becomes a mainstream sport and that it will inspire fans to start building and flying drones.

“That’s the responsibility all of us have with drone racing, is, we want this to be accessible,” Foxhoven says. “We want the public to watch it and find this interesting. For the majority of the public, they’re not flying drones right now, but we want them to find it to be exciting enough to pick one up and fly it.”