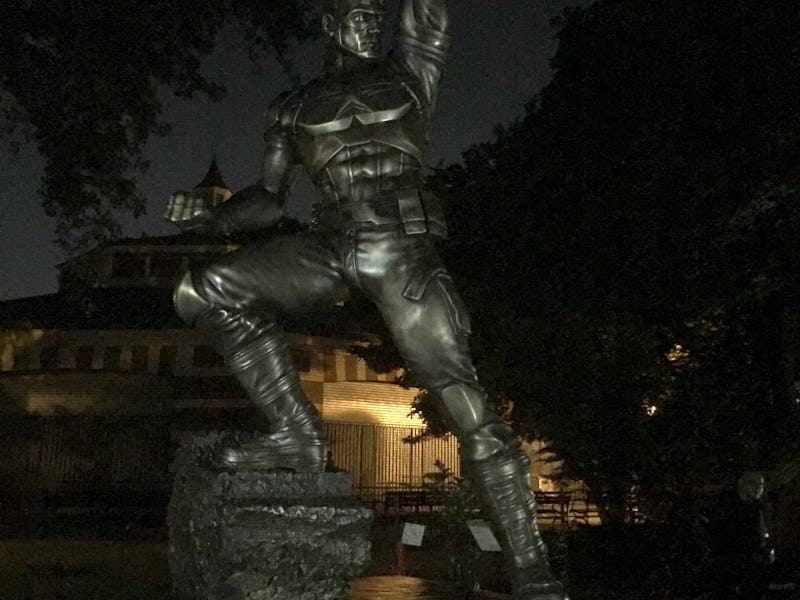

Why is Captain America Hanging in a Brooklyn Park at Night?

It's complicated. Way more complicated than it looks.

Captain America has plenty to fear from an empty park in Brooklyn. That’s why Joe, a retired police officer-turned-private detective, was hired by the city to keep watch over the one-ton, 13-foot-tall, Marvel-donated statue in Prospect Park on the eve of the big unveiling. The statue will do a two-week stint next to a carousel, next to the zoo, before bringing its star power to the Barclay’s Center, one of the few NBA arenas without any stars to call its own. Joe, who does a lot of protection work for ABC — and, by the transitive property, Disney — says the only unusual thing about this gig is that the statue isn’t under a tarp. Steve Rogers don’t hide.

This immodesty is thrilling for two Pokémon Go players out for an augmented reality jog, but it doesn’t do much for Joe, who is wearing a sports coat while manning a post in a public park at 10 p.m. on a Tuesday and doesn’t give a shit about superhero stuff. Whatever the statue represents, it doesn’t represent Joe.

The inscription on the side of the tribute provides a hint about why it’s here. “I’m just a kid from Brooklyn,” it says above the words, “HOMETOWN PRIDE.”

Since Jack Kirby first put him on the cover of a comic book in March, 1941, Captain America has always presented a slight twist on the classic “local boy makes good” mythos. “Local boy made good by refugee semitic German scientist” just has less of a ring to it. But the notion that Rogers’s localness is somehow relevant to the folks grabbing a stoned bite at the Wendy’s across Empire Boulevard is pretty easy to dismiss. Rogers is an AngloSaxon name. Were Cap Italian, Irish, Polish, African-American, Latin, Jewish, or Russian, his localness might still track — tribal identities feed into the larger Brooklyn identity — but he’s emphatically, almost impossible not. He’s got that aquiline nose and the altar boy hair. He is what the census used to refer to as “native born white.”

A rendering of the statue, which has a lot of stars on it.

This is all to say that Roger’s Brooklyn-ness long since stopped being about Brooklyn, which makes the statue a weirdly literal tribute to an abstract idea. The Brooklyn Captain America really hails from is a developmental stage. Cap’s Brooklyn represents the authenticity of adolescence and its proximity to the artifice of adulthood, which looms large across a river of hormones. Captain America represents the teenage idealism of the sort of boy who fantasizes about earning the girl’s affections rather than having her.

There are certainly dumber sentiments to build a statue to than that. There are several panthers standing on top of plinths in Prospect park for no reason at all — other than that panthers are dope.

Still, there’s a problem with the Captain America statue that doesn’t have to deal with the distinctions between art and commerce that have some locals equating the sculpture to a billboard. That problem is that Captain America is a militant and/or military figure. He’s holding a shield and his formidable fist is clenched. At best, this belligerent contrapposto is a reminder that a lot of people from around Brooklyn put a serious hurt on the Nazis. Those fighters’ descendants — for a wide variety of economic and demographic reasons — don’t live here any more, but that doesn’t make the “Don’t fuck with BK” moral of the story any less heartwarming.

But then there’s the uniform.

Captain America is not wearing the uniform he wore when he fought the Nazis. He’s wearing a modern outfit, which means he must be representing modern American interests and ideals – which is where things get a bit hairy and a little bit odd. Captain America is 75 years old this month. Thus the statue. And though he’s spry, he still has the basic skill sets of highly competent 75-year-old. He might be able to hot-wire a car (or throw it), but he’d probably screw up programming the in-dash computer. He’s a hammer in a world full of screws. That may have been what Civil War, his last cinematic adventure was about, though, honestly, it’s hard to say.

What’s ultimately clear when you stand in front of the statue in the middle of the night is that it represents, more than anything else, economic and geopolitical wishful thinking. Born lower-middle class, Steve Rogers gains access to the corridors of power by being a good guy and doing the right thing. The muscles are essentially his reward for winning the Mr. Congeniality award during army training. He wears them well, goes to war, and returns a hero with higher social standing. Like the Americans he protects, Captain America is the beneficiary of his own service. That was how it was supposed to go — and how it went — for a lot of the boys from Brooklyn who kicked German ass (twice). But that handshake deal between the brass and the grunts fell apart over the latter half of the twentieth century. Does the narrative of military betterment still resonate in the 21st century? To an exceptional few, no doubt. But Captain America’s rise to prominence no longer makes him archetypal. It makes him old.

And then we’ve got to go back to the fist. There are plenty of bad actors in the world and most of them would likely react to the ball of knuckles by asking the same question: “What are you going to do with that? There are evil people in the world, same as there ever were, but punching them now feels like a total waste of time. We’ve come to understand bad actors as the products of flawed systems and historical dynamics. The unfortunate truth is that you can’t punch ISIS in the face and fighting hackers is more about finding them than hurting them. There’s also this: America has been so dominant for so long that any opposition to that power takes the form of guerrilla warfare. Captain America is just a boy from Brooklyn who became an enforcer — and not a very effective one at that.

What’s weird about the Captain America statue isn’t that it exists. It’s that it exists at night. Without the context of fans or kids or explosions or marketers, it’s not ennobling and it doesn’t even feel specific to Marvel or the movies. It’s a memorial to a pre-forgotten idea — a memory of a dream about that commercial you saw the one time. It’s a weird statue of a tough guy in tight pants holding a wok.

Joe, the statue’s rent-a-Bucky for the night, seems like the sort of guy who could deliver a beating if called upon to do so. But he doesn’t think that’s gonna happen. He thinks it will be quiet after the park closes at 1 a.m. Sure, there could be bad guys in the shadows. But they tend to stay there these days.